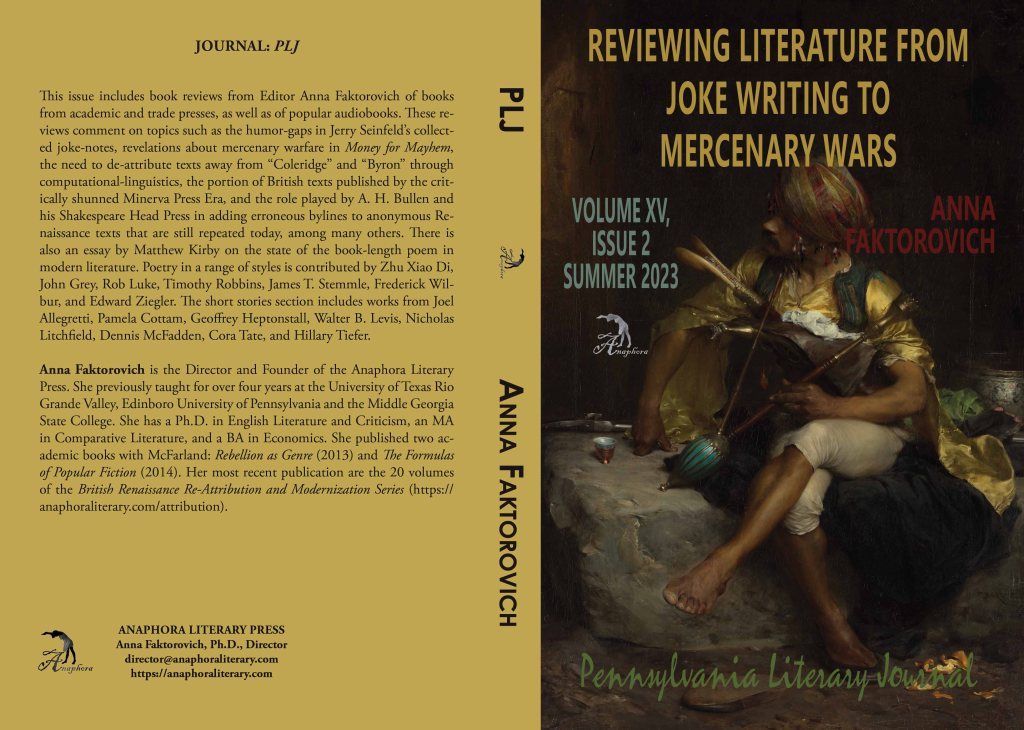

By: Anna Faktorovich

Jerry Seinfeld’s Unedited Diary of Attempted Funny Thoughts

Jerry Seinfeld, Is This Anything? (New York: Simon & Schuster, November 9, 2021). $18. EBook. 480pp. ISBN: 978-1-982112-72-1.

***

“The first book in twenty-five years from… Seinfeld’s best work across five decades in comedy. Since his first performance at the… New York nightclub Catch a Rising Star as a twenty-one-year-old college student in fall of 1975, Jerry Seinfeld has written his own material and saved everything. ‘Whenever I came up with a funny bit, whether it happened on a stage, in a conversation, or working it out on my preferred canvas, the big yellow legal pad, I kept it in one of those old school accordion folders,’ Seinfeld writes. ‘So I have everything I thought was worth saving from forty-five years of hacking away at this for all I was worth.’ For this book, Jerry Seinfeld has selected his favorite material, organized decade by decade. In this” collection “you will witness the evolution of” a comedian “and gain new insights into the thrilling but unforgiving art of writing stand-up comedy.”

Seinfeld opens the book by reporting that he was influenced to start a comedy career by reading Phil Berger’s The Last Laugh and watching Dustin Hoffman’s film Lenny. Instead of finding some deep essence of the formulas of comedy, he was captivated by a scene in the movie where the comedian eats and flirts with a stripper, instead of worrying if the set he just delivered was a comedic success. As long as a comedian can be “funny” or elicit laughter, they could profit and gain the fineries of life. (Purchasing laughs from the audience, or comedians exchanging laughter with fellow comedians are probably the tricks that get the laughs even if a given comedian is not technically funny. But Seinfeld does not go into such illicit subjects.) Seinfeld does confess that he struggled with “story structure” or with acting dialogue without “funny” lines during his school production days and later. Then, he begins talking about the act of performing comedy, and digresses into the different chemicals in the brain that supposedly make things funny (as opposed to the structure of the jokes). He describes an addiction to hearing laughter. One curious thing he mentions in this introduction is that fellow comedians were “surprised” to learn that he “kept all these notes” from his years of performing. They were probably surprised because most of them must hire ghostwriters to write their material, or they might steal much of it from other comedians. So for them, publishing a volume of this content is likely to trigger a plagiarism lawsuit. Whereas spoken words from many performances are otherwise difficult to group together and transcribe for a lawsuit. And if they hire ghostwriters, they wouldn’t retain “yellow” notepads or any other handwritten records of the stages of authorship involved in actually writing content themselves. Thus, the fact that Seinfeld is publishing this book, and includes some handwritten samples is a good indicator that he might be one of the rare comedians who actually writes their own comedy. Seinfeld acknowledges this likelihood, noting that “Comedians like Bob Hope and Jack Benny would actually joke about their writers as part of their act.” Seinfeld adds that in the 80s Barry Marder was selling his jokes at the Comedy Store in LA for “$75 a joke.” This is a very frank confession that I haven’t seen in other books about comedy writing. The rate is so high because of the before-mentioned addiction comedians have to hearing laughter or appreciation from an audience. Then Seinfeld mentions that telling somebody to become a comedian is like telling them they could become an “iguana”: “If you don’t have those crazy eyes, leathery skin and the long tongue, it’s tough to get there.” I actually laughed on this note. I rarely laugh at any type of comedy aloud, so Seinfeld must know what he’s doing, even as he’s insisting it’s just a matter of intuition and chemistry.

However, as one starts reading the raw jokes themselves (first from the 70s) it becomes clear why most comedians don’t share their rough notes. “Bumper Cars” is a diary entry about the brutality of this experience, with repetitions and childish defensiveness. Then, the “Cotton Balls” entry keeps repeating that women’s bathrooms are scary because there are too many cotton balls, and Seinfeld can’t figure out what women do with them and other stuff in there; the story keeps repeating, but snowballs into the conspiracy of the Cotton Ball Syndicate.

To check if the jokes evolve, I check the later sections. In the 80s, there’s an entry on “Airport Cart People”, which basically ridicules people who are “too fat, slow, and disoriented to get to your gate on time” without using a cart; in other words, it’s making fun of disabled people by pointing out that they inconvenience body-abled people who have to get out of their way. In the 90s, there’s an entry on the “Psychiatrist”, with a question why a 1-hour session really takes only 50 minutes. Finally, a more inspired set of jokes appears in a section on “Money”, where he argues that he has “not done well as an investor in things”, and instead of having money “working” for him, he has decided to do the work, while letting his money “relax”. But then the story devolves into questioning credit card checks, and it seems more like just what he wrote down while he was waiting for a check in a restaurant. This is a realistic documentation of what’s going on in the mind of a comedian. But reading these types of notes is not likely to help comedians who are looking for completed jokes that they can study to understand the structure of the types of stories that have succeeded in getting laughter for Seinfeld across his decades of experience. The final “Teens” section begins with a story on “Annoying Friends”, which mentions the most common conversations with friends around meeting, such as “Did you eat?” and “This guy’s huge”, so they have to go to see a show of his performance. The last piece in the book is “Flex Seal”, which is an ad for this TV infomercial show; the story is interrupted by the threat of a flood killing everybody, but then it repeats what’s good about this nonsensical sealing product.

This book proves that comedians who keep their full notes private are right to do so, as these extensive notes are unreadable as a set. A joke is funny when it surprises an audience, and this is possible from a short spontaneous introduction to an absurdity of otherness in a set. But this element of surprise disappears as one reads the larger flow of similar thoughts or general observations that just begin to echo ideas anybody might have in similar circumstances. Shock then is instead derived from offensive or strange reactions to otherwise common occurrences. And these types of negatively shocking observations tend to both not be funny, and also not be acceptable to modern tastes in regard to social proprieties. I do not recommend readers to purchase this book. If they are comedians, they will assume that they can make people laugh by just saying whatever comes to mind on any given outing. If they are just interested in a laugh, they will instead find the clutter of thoughts, most of which has to be deleted during attempted performances to only leave the tiny bits that actually bring about laughter.

Difficulties in Researching the Fiscally-Profiteering Villains Behind Mercenary Warfare

Alessandro Arduino, Money for Mayhem: Mercenaries, Private Military Companies, Drones, and the Future of War (New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, October 15, 2023). Hardcover: $38.00. 298pp. Index. ISBN: 978-1-538170-31-1.

*****

“The way war is waged is evolving quickly—igniting the rapid rise of private military contractors who offer military-style services as part of their core business model. When private actors take up state security, their incentives are not to end war and conflict but to manage the threat only enough to remain relevant.” It can be easily argued that governments are far more fiscally self-interested in continuing wars forever, as military salaries and promotions are more certain than private contracts that can have a firm termination date. “Arduino unpacks the tradeoffs involved when conflict is increasingly waged by professional outfits that thrive on chaos rather than national armies. This book charts the rise of private military actors from Russia, China, and the Middle East using primary source data, in-person interviews, and field research amongst operations in conflict zones around the world.” This list of countries excludes the US, so it seems to be biased towards the US contractors’ rivals, as opposed to being a general attack on international profit-driven warfare. “Individual stories narrated by mercenaries, military trainers, security entrepreneurs, hackers, and drone pilots are used to introduce themes… Arduino concludes by considering today’s trajectories in the deployment of mercenaries by states, corporations, or even terrorist organizations and what it will mean for the future of conflict… The book specifically reveals the risk that unaccountable mercenaries pose in increasing the threshold for conflict, the threat to traditional military forces, the corruption in political circles, and the rising threat of proxy conflicts in the US rivalry with China and Russia.” Dr. Alessandro Arduino bias stems in his specialization (among other topics) on counter-China research into China’s Belt and Road Initiative security in Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia. “Arduino is an affiliate lecturer at the Lau China Institute at King’s College London, a fellow at the China Africa Research Initiative at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies”.

This review copy came through NetGalley, which I am using to review books for the first time. This is also a rare pre-release pdf with “uncorrected proofs”. It took me some time to figure out how to access this copy, until I downloaded the NetGalley app on my phone. Since this is a pdf, this means that an entire book’s page is fitting into my phone’s window. I changed the perspective to horizontal for the letters to be regularly-sized; this means there is a lot of scrolling across and between pages. Despite this being a pdf, there was no decipherable option for downloading this book to view it on my computer.

The table of contents demonstrates that there are a lot of different sub-groups, contractors, national players and conflicts covered across this book that make for nuanced findings on the larger question of private warfare. The warfare covered is also not only the kind with bombs and bullets, but also cybercrime. There is a section within “Chapter 10: Drone Mercenaries: A New Security Paradigms from China, Russia, and Turkey” that covers “U.S. Earlier Drone Supremacy: Remote Assassination”, which is sandwiched between sections on the adversaries mentioned in the chapter’s title. Sean McFate’s “Foreword” also considers the other side, as it notes: “Today, you can rent former U.S. Special Operations Forces troops”. Though while Russian affiliates like the Wagner Groups are described as being involved in helping negative rulers in Africa, American mercenaries are portrayed as saving somebody like a Nissan CEO “from house arrest in Tokyo”. A different way of saying it is that the Americans broke somebody out of imprisonment and took him to a non-extradition country; but this illegal activity is positively spun. The “Foreword” does point out that there is a problem with all of these activities because private military groups can “resist arrest” by shooting law enforcement coming after them from state actors, and there are currently no international laws capable of reprimanding such extreme disobeying of laws that all other people have to follow. Any non-capitalistically minded group that fired back at law enforcement and came from abroad would probably be branded as a terrorist, but the mere open exchange of corporate funds shields such activities.

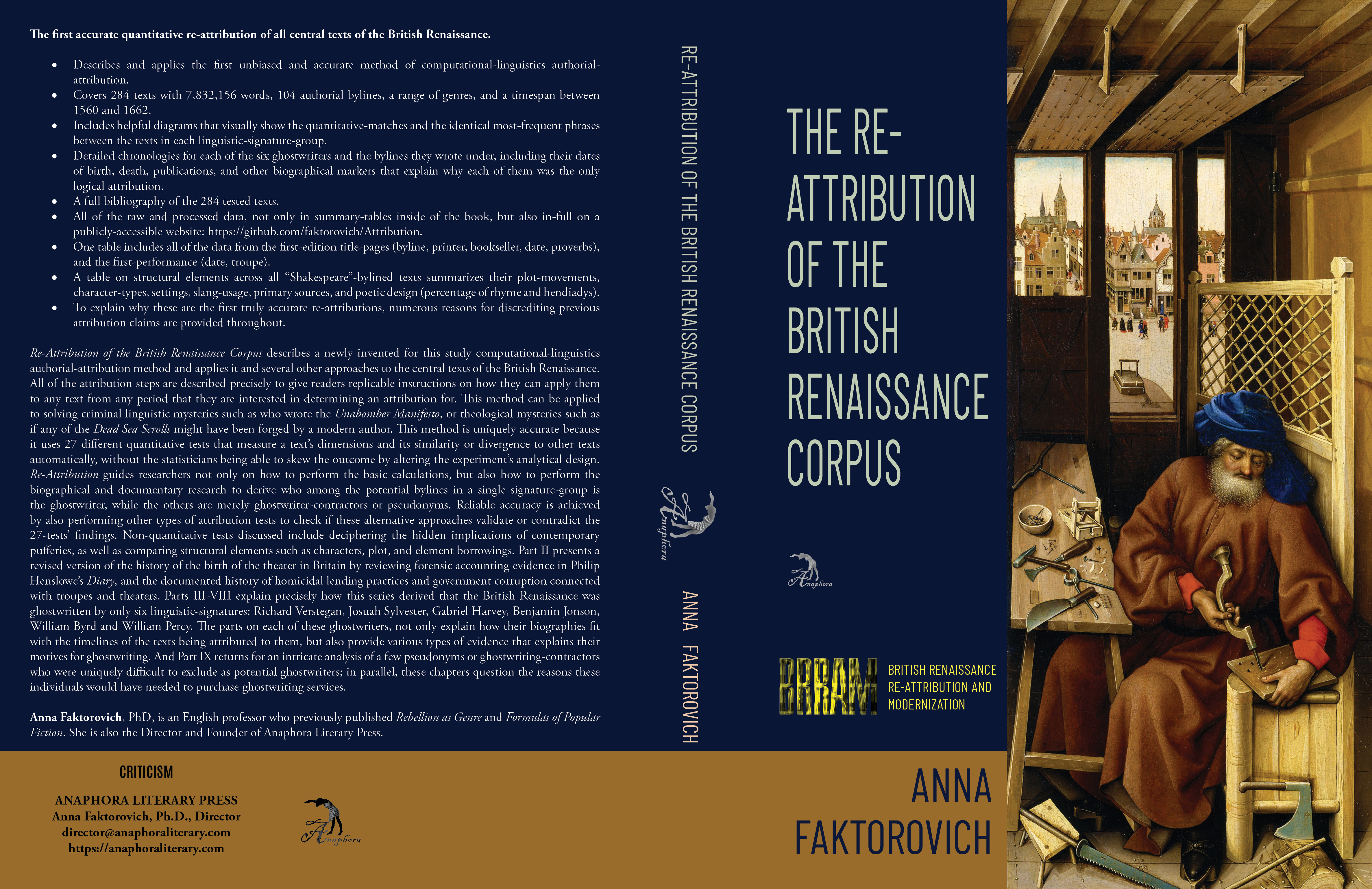

The “mercenary arms race” is presented as a spiking new phenomenon, but my BRRAM research identified it as being at the core of modern warfare from at least the Renaissance. Richard Verstegan was ghostwriting on various sides of conflicts, and profiting from starting and continuing wars and disagreements; he deliberately offended rival states in the press, and created suspicion, mistrust, and nationalist fervor in the texts he ghostwrote for Catholics as well as for Protestants, or for England and also for the Pope; the more animosity he could generate in counter/propaganda, the more books he sold, the more pension funds he received for his self-espionage, and the like. The same profiteering from generating the pro-war narrative is still thriving with very similar modes today. The very terminology in the “War on Terror” is a major part of this artificial creation of enemies by bombing and killing minority groups to push them into actually becoming enemies that need to hire propagandists and militias of their own to fight back against the onslaught. If the profit motive was removed and nobody could benefit from writing/publishing pro-war propaganda, and nobody could make a salary from firing weaponry; then, there would be no more warfare on earth. Only propagandistic fictions can imagine a motive for any group to attack any other group, instead of peacefully coexisting and conducting mutually beneficial business. The “Foreword” aptly brings in a quote from a “fourteenth-century Italian writer Franco Sacchetti” that explains in a parable that just as monks profit from alms, mercenaries profit from the continuation of warfare. But McFate does not learn from this example, as the conclusion he draws is that the market for mercenaries is just a tool that can be sed for good and evil means. In contrast, the lesson of the parable is that the marketplace of warfare itself is evil, as opposed to any specific players within this game.

“Chapter One: Private Armies” explains that the 1989 UN International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing and Training of Mercenaries (or cross-country for-profit warfare fighters) prohibited the use of mercenaries “but no specific body at the international level is tasked to monitor, oversee, and guide the implementation of the convention”. In other words, both US and foreign businesses who engage in all activities described across this book are breaking international law, but there is no international court capable of enforcing this legal boundary, and so all sides are carrying on with it, and bringing millions of death and much property destruction as they proceed. Arduino notes that there was a lull in “full-scale wars between sovereign nation-states” between the end of the colonial era, the world wars and the “U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq”. U.S. had previously invaded and attacked Korea and other nation-states, but Arduino seems to be classifying these as too minor to count in the overall data. From the broader perspective, the U.S. has been violating with warfare countries across the globe between WWII and the present moment, and Russia has just taken a relative break from these activities between the fall of the USSR and the present Ukraine war. Arduino uses the history of Romans hiring mercenaries to claim that such profiteering is a normal part of human activities. But my findings regarding the tendency to create falsehoods or fictions that fit a propagandistic argument indicate that much of ancient history is likely to have been imagined by later historians, who are not likely to have had much surviving written evidence to base their claims on. Thus, the military habits of the sponsors of these propagandists might be skewing our perspective on just how rare mercenary warfare or warfare in general was until the last 500 years when print and the fictional propaganda it can spread has influenced our perceptions of who our “enemies” (or “barbarians” as the Roman propagandists called them) are.

When Arduino looks at specific examples of mercenary activities from the hostile actors depicted in this book the narrative becomes cloudy. For example, there is an oligopoly of a few “top Chinese private security firms” that help protect international Chinese business and state operations, and the Chinese are hesitant to hire non-Chinese protection services; this is a basic statement of nationalist propaganda, and yet it is proposed as if it is an aggressive act that China is taking, by refusing to hire Western mercenaries. Just as Blackwater is profiting from a constant anti-Jihad sentiment; there is a Malhama Tactical Group that is a “Blackwater of Jihad” outfit that is providing “training for profit to Al Qaeda affiliates in Syria and Africa”. The problem from Arduino’s perspective seems to be that Western mercenaries and nations cannot “win” the conflicts they are profiting from if the other side is also pumping funds to oppose their efforts. Another problem that Arduino is concerned about is one that affects him personally, or that researchers like himself can be accused of espionage for “snooping” into Chinese or Russian mercenary affairs in the current militant international climate. Examples of this include the espionage charges against the Wall Street Journal reporter, Evan Gershkovich, in Russia. Such researchers now need to register as a “foreign agent” to avoid “detention”. However, the “suicides” or alleged robberies that have been cited as causes of death for several researchers looking into Russian contractors can also be seen as similar activities to how U.S. mercenaries “freed” a Japanese businessman from imprisonment through violent means. If U.S. actors can assassinate Iraqi or Afghan politicians or business leaders by labeling them as terrorists; this eliminates the moral high-ground of outrage against similar activities from the other sides. In the Ukrainian conflict, one of the big mysteries is who is bombing sites in Russia and attacking troublesome places such as commercial bridges, or attempting assassinations; when Ukraine does not take official credit for these operations, it suggests that mercenaries or terrorist actors are “derailing peace negotiations”. Since profit-seeking entities would blatantly be interested in such derailments, figuring out who is responsible can help bring about a peaceful resolution for all sides. The little “coup” the Wagner group staged in marching on Moscow is also confusing, as it seems to have been orchestrated to diffuse attention away from it and other profiteers of being responsible for the conflict, by reframing them as an entity that is interested in peace, but is being forced into warfare by Russia’s autocrats. Arduino explains that the lack of information on the Wagner Group’s source of funding is a major hurdle to solving this whodunnit. This seemingly is a very simple mystery to solve, as a forensic accountant with access to records in a couple of countries should crack this case. So the real mystery is why a team of accountants hasn’t been launched to help end the Ukraine war. In fact, Arduino is the accountant or researcher who should have solved this question in this book, but instead this chapter is presenting questions and arguing that such investigations are impossible. Arduino points out that in the U.S. “the first wave of public criticism on contractors was ignited in 2007 by the Nisour Square massacre when Blackwater operators indiscriminately opened fire on Iraqi civilians, killing seventeen bystanders”. But Arduino makes it seem as if this was an isolated incident that withdrew the main actor, Blackwater, out of the conflict; in contrast, there have been millions of civilians that have been killed in Iraq and Afghanistan by both mercenary and military Americans, so these incidents have remained common; it is only the media coverage of these problems that has eased up, or stopped portraying such bloodshed as crimes against humanity. Arduino also explains that the maneuvers that move mercenaries away from conflicts when a side decides to claim they have already “won” can immediately shift power to the opposition (as during the “fall of Kabul” in 2021. Funding warfare against an enemy generates a need for self-defense from a potentially previously peaceful population; and then withdrawing funding for a sub-groups self-defense can cause tyrannical takeovers of regions by the most violent paid-for militias in the region. Arduino mentions a curious problem: the invasion of Crimea by Russia a decade ago triggered western sanctions that limited Russia’s government budget; this restriction led to an increased desperate need to “win” the conflict through open warfare with Ukraine as a whole; and now that a “win” for Russia appears impossible, they seem to be stuck in a death-spiral. If mercenaries such as the Wagner Group have been profiting across this decade from fighting in Ukraine without Russia’s governmental military force; then, the war had to have been prevented by limiting the availability of such mercenary war-waging or defending powers. And after the pure-profit motive is withdrawn and the war becomes a struggle over nationalistic concepts such as Russian or Ukrainian pride, the war can only be ended by propagandists on both sides letting go of this death-grip spiral, but such a fictive turn-around is difficult, as it is difficult to explain the point of thousands of lost lives and the destruction of cities if the nationalist motive is deflated into being insignificant. Arduino also explains that the need to hire mercenaries in the Middle East and North Africa is partly due to the threat Russia faces of otherwise losing “access to sea lanes of communication and natural resources”. In other words, the sanctions western and other actors place on Russia and China are creating the very threat of a loss of communications or resources that makes mercenary or governmental violence a necessity to defend the basic interests of the Russian people to access resources like food and gas. In this case, avoiding sanctions on the people, and instead creating international laws that punish those who kill for profit is the simple solution that Arduino fails to imagine. This is where Arduino’s note that “only fragments of evidence have emerged over” Wagner Group’s “origin and the contractor’s involvement in combat operations” is so problematic. Finding these fiscal roots and branches might end several wars across large portions of the world, so there should be at least as much funding invested in this effort as in sending weaponry to help the various sides defend themselves against this Group. Arduino doubts that Prigozhin is the Wagner Group’s “puppet master”. And indeed, it is possible that this Group’s puppet master is an American business man who is also investing in American mercenary and governmental groups and profits from creating an enemy by being paid to defend against this enemy.

In the second chapter, Arduino notes that Chechyan President Kadyrov has cited that the FBI had a “$250,000… bounty… on Prigozhin’s head”, and this convinced him to send his troops to support Putin’s in Ukraine, just so he could attempt to catch Prigozhin and claim this bounty. Here is an obvious profit to be gained in going after a specific named “enemy”. Why the stated “enemy” is “evil” and worthy of capture or assassination is a debate for propagandists. The real problem is that all sides buy into the legality of such violent cross-boundary intrusions that cannot be policed by rational courts in the countries involved. Arduino notes that this general philosophy of aggression might be rooted in “the role Western mercenaries” played in “Africa in the 1980s”, through their monopolization of the “postcolonial” or anti-colonial fight by “mercenary groups such as the… Executive Outcomes (EO)”. It is easy for propagandists to explain all colonialism as evil, and if there is a clear moral “enemy”; then, it is not a violation of human rights to slaughter this enemy, even if it is replaced with a far more brutal and repressive totalitarian military regime. A private military group can be sponsored to enter a zone to make it seem as if a region is rebellious to justify the use of a much larger militant group to suppress this fictionally generated “enemy”. All such conflicts would end if researchers were purely interested in learning and disseminating the truth, as locating the true beneficiaries of warfare is likely to concentrate the “enemy” in a handful of profiteers, instead of on any ethnicity, class, race, or nationality.

If this was a book from an academic press, I would complain that across the first few chapters the author only mentioned a few facts, and instead spent most of these pages on speculation. But since this is a trade title, and it managed to keep me reading every word for around 50 pages, it is clear that it has succeeded in drawing a reader into its web. There are enough new facts presented that I had some quotes to offer to explain the various theoretical questions that this content raised in my imagination. If I had previously reviewed many other books on this topic, it might have been less surprising. But given my relative ignorance on this topic, it was very useful in helping me to understand the much lighter strokes with which these mercenary conflicts tend to be explained in the media. There is clearly a need for somebody to dive much deeper into the fiscal and contractual evidence, but perhaps this author does so across the rest of the book, introducing bits of information separately, instead of clustering it as tightly as it needs to be woven in an academic book. Thus, all who are similarly interested in understanding modern warfare and profiteering are also likely to enjoy reading this book casually. So it is a good fit for libraries of all types, and even private readers might enjoy purchasing it for their private libraries (I infrequently give the latter recommendation, as I tend to be cheap in such expenditures, preferring free review copies).

Non-Linear Digressions on Gendered Modern English Etymology

Jenni Nuttall, Mother Tongue: The Surprising History of Women’s Words (New York: Penguin Group: Viking, August 29, 2023). 304pp. ISBN: 978-0-593299-57-9.

***

A “linguistic journey through a thousand years of feminist language—and what we can learn from the vivid vocabulary that English once had for women’s bodies, experiences, and sexuality. So many of the words that we use to chronicle women’s lives feel awkward or alien. Medical terms are scrupulously accurate but antiseptic. Slang and obscenities have shock value, yet they perpetuate taboos. Where are the plain, honest words for women’s daily lives?” This “is a historical investigation of feminist language and thought, from the dawn of Old English to the present day.” A guide “through the evolution of words that we have used to describe female bodies, menstruation, women’s sexuality, the consequences of male violence, childbirth, women’s paid and unpaid work, and gender… Examining the long-forgotten words once used in English for female sexual and reproductive organs. Nuttall also tells the story of words like womb and breast, whose meanings have changed over time, as well as how anatomical words such as hysteria and hysterical came to have such loaded legacies.”

My BRRAM series includes the first Old English diction in my modern translation of Verstegan’s Restitution for Decayed Intelligence in Antiquities (1605). There is no Index yet in this galley edition, and there is no search option for me to check if Verstegan is ever mentioned. Surprisingly, Verstegan is mentioned in the “Introduction” (but without a citation for my translation in the “Notes”), where she uses him as an example of sexist language as his definition for “woman” indicates a “womb-man”. Because Verstegan basically forged or invented the definitions and etymologies for Old English before anybody else attempted decoding this language, and because he was instrumental in forming the Early Modern English language; if one of Verstegan’s definitions is sexist, then the term was meant to be sexist by its creator. Nuttall argues that “woman in truth comes from the Old English compound wifman, or woman-human; Nuttall does not quote the source of who first defined wif as woman, but she notes that scholars disagree on this point. She also claims the author typically gives answers regarding the derivation of Old English words from the top of her mind, and only occasionally looks up these origins. This suggests she probably puts little value in the origins of these dictionaries and how their derivations were developed. She mentions the Oxford English Dictionary in the following clarification as a main source; this dictionary’s etymology is an echo of generations of earlier etymological dictionaries, so it is likely to have many mistakes that have appeared through the ages. Verstegan’s etymology is heavily built from German, Dutch, Latin and other languages that he was familiar with that guided him in understanding united Old English/German roots. I offer a comparative set of etymologies from different sources, and support or negate Verstegan’s definitions across my translation of this dictionary and all of its words, so I would recommend for those interested in the full range of English derivations to read my own translation instead of this book. For example, Nuttall accepts the standard narrative that Old English arrived in England in the 400-500s, when my study explains that DNA studies have concluded that most of the current British population migrated to the islands in the 900s. The early migration theory comes from fictional narratives of “King Arthur” and the like that have been erroneously interpreted as history.

Instead of focusing on researching the actual origins and debates about specific words, most of this book is a feminist diatribe, as in: “Women’s paths through the world, whether they liked it or not, were predetermined and constricted because they had been selected for certain treatment on the basis of their particular reproductive anatomy” (21). The reason for widespread sexism across the Renaissance is because there were no female authors among the six male ghostwriters (as BRRAM illustrates), and texts assigned to female bylines like “Elizabeth I” or “Mary Sidney” were actually ghostwritten by men, who made it seem that women were approving of the sexist stereotypes that chained them from accessing an education. The continuation of the myth that women participated in this Early Modern English creation process is the real problem with understanding the roots of bias in this language. Instead, Nuttall is concerned with being called a “vulva-owner” (14). I personally don’t understand the problem with this usage, as it’s a biological fact that I own a vulva… Nuttall “solves” these mysteries by looking up Latin-derived terms like “labia” in the Oxford English Dictionary, which claims “vulva” originated in around 1400. During my translation I learned that checking online sources for terms tends to surface earlier (or even stranger only later) usages and occasionally their usage in other languages than what mainstream dictionaries tend to cite. The problem here is that Nuttall is to conversational, as she chats and asks questions, and only inserts a few etymological claims, without annotation numbers next to the claims to explain their origins, which suggests she is just using OED. Then, Nuttall refers to Aelfric’s Bible explainer from 1000, without acknowledging that Verstegan was implicated in some of the forgeries of Old English texts by translating Latin biblical works into Old English himself to claim their antique value in the book versions he published; this can mean that checking a term against Aelfric’s definition might again be a citation of Verstegan (most of these documents have never been scientifically dated).

Nuttall’s text really needs sections and subsections to explain how her ideas are organized. For example, a section begins seemingly by attempting to figure out the roots of “the first English words for female reproductive anatomy”. There is a note that “English has some of the oldest medical guides written not in Latin, the common language of scholarship, but in the mother tongue” (19). The reason for this is because Verstegan forged some of these documents and backdated them; if there was no backdating going on, Britain should have similarly dated “oldest” documents in non-Latin or Vulgar Latin languages as the rest of Europe. Another sign of forgery is, as Nuttall notes, that a major “chapter 60 of Book II” is “now infuriatingly missing”, and it had promised to explain “forty-one cures for gynecological and obstetric problems”. Obviously, it was easier to not write a forgery of such an undertaking. Even if these documents are authentic and were not forged, Nuttall explains that they were unspecific and thus non-sexist as they referred to both male and female genitals as “gecynd”, including a generalist term -kind that Nuttall frequently returns to (20). Nuttall then digresses about the various other terms that have similar or multiple meanings. The discussion is generally scattered. This is a problem for any students or researchers who just want to see a specific full derivation with all sources an options listed together and compared for the different specific terms they might use in their common language, or might need to derive in their research.

There is a great idea behind this book, but the author hasn’t begun organizing, re-framing, or truly archivally researching it to arrive at some new understanding of this rich but deeply misunderstood field. I do not recommend for the public or scholars to read this book, as it will deeply confuse them without enlightening them on what gendered English language means.

The Type of Nonsense That Drives Conspiracy-Followers to Murder

Colin Dickey, Under the Eye of Power: How Fear of Secret Societies Shapes American Democracy (New York: Penguin Group: Viking, July 11, 2023). 326pp. ISBN: 978-0-593299-45-6.

**

“From the American Revolution (thought by some to be a conspiracy organized by the French) to the Salem witch trials to the Satanic Panic, the Illuminati, and QAnon, one of the most enduring narratives that defines the United States is simply this: secret groups are conspiring to pervert the will of the people and the rule of law… History tells us, in fact, that they are woven into the fabric of American democracy… The history of America through its paranoias and fears of secret societies, while seeking to explain why so many people—including some of the most powerful people in the country—continue to subscribe to these conspiracy theories. Paradoxically, he finds, belief in the fantastical and conspiratorial can be more soothing than what we fear the most: the chaos and randomness of history, the rising and falling of fortunes in America, and the messiness of democracy. Only in seeing the cycle of this history, Dickey says, can we break it.”

The front-matter regurgitates this blurb in numerous cycles of repetition, as it builds up a frenzy against conspiracy theories in general, with only brief mentions of any specific absurd theories. The first specific section, “One: The Arch and the Cenotaph”, opens with an extremely general description of a “landscape” with a “stone arch”, which is eventually explained as a monument that was repaired with a fundraising campaign by the Freemasons. Dickey narrates his stroll around this arch and his observations, as if he received funding for this trip, and this is his proof he actually went. He focuses on the Eye of Providence emblem the Freemasons engraved during their renovations; Dickey briefly mentions it is a symbol that appears on the dollar bill, before suddenly turning this into a conspiracy of the eye signifying the Freemasons’ “plans for world domination”. The next section digresses about random anonymous slanders cast at Freemasons on sites like 4chan. While the evidence on these sites is as non-specific as what Dickey repeats here, Dickey does point out that this nonsense has generated real arrests by the FBI, such as the arrest in 2016 of a guy who “was planning an attack on the Freemason temple in Milwaukee”. And there was a 2004 attack on a Masonic lodge. At least some of these attackers are “Neo-Nazis”.

Given my own findings regarding the prevalence of ghostwriters (6 in the Renaissance, 10 in the 18th century and 11 in the 19th) who have controlled British history between at least 1550-1899, there are indeed tiny groups of people who have undue influence, but these people are not wasting their time wearing robes and chanting, but rather are busy ghostwriting or otherwise planting influence anonymously. They do not confess their membership in a club, nor have churches where they can be taken out as a group. A ghostwriter can be contracted to create conspiracy theories against power-swaying organizations like Freemasons in order to diverge attention away from the actual players (like himself). The overflow of fake conspiracy theories helps to secure the safety of the real conspirators, who can dismiss accusations against them as “mere conspiracy theories”. This is precisely what Dickey’s book is doing; it is using digressive and fluffy language to create a sense that all conspiracies are nonsensical or threatening, instead of investigating both true and untrue conspiracies and showing how they can be distinguished. There is some sense amidst the nonsense, like the historical explanation that the Eye originated as a symbol referring to the trinity during the Renaissance, and then was adopted by the US Founding Fathers because it had a different meaning referring to “strength and duration”. And there is a note that Freemasons actually adopted this symbol after the Founders, as opposed to before; so the Founders did not intend to put a Freemason symbol in their documents, but rather the Freemasons took advantage of a symbol that already had power as an American symbol. But all these explanations are without citations, and are continuously interrupted with asides, ponderings, and the continuing tour the author is on.

This book is not recommended for researchers who need sources to explain the covered conspiracy theories, as this information is probably easier to find online and in a more approachable format. And those who want to question or find affirmation in conspiracy theories they are questioning will become very frustrated, if they attempt this book, as it will take them on many tours they do not want to be on.

A Digressive Biography of a Professional Female Author: Willa Cather

Benjamin Taylor, Chasing Bright Medusas: A Life of Willa Cather (New York: Penguin Group: Viking, November 14, 2023). 123pp. ISBN: 978-0-593298-82-4.

***

“The story of Willa Cather” (1873-1947) “is defined by a lifetime of determination, struggle, and gradual emergence. Some show their full powers early, yet Cather was the opposite—she took her time and transformed herself by stages. The writer who leapt to the forefront of American letters with O Pioneers! (1913), The Song of the Lark (1915), and My Ántonia (1918) was already well into middle age. Through years of provincial journalism in Nebraska, brief spells of teaching, and editorial work on magazines, she persevered in pursuit of the ultimate goal—literary immortality. Unlike Hemingway, Faulkner, and Fitzgerald, her idealism was unironic, and she stood alone among the great modern authors—at odds with the fashionable attitudes of her time… Taylor uncovers the reality of Cather’s artistic development, from modest beginnings to the triumphs of her mature years.”

This is a very frustrating biography to read. The introductory comments flitter between puffing her different books, celebrating her western origins, and quoting her non-fiction communications. Then, the “One: To a Desert Place” chapter begins with a digression on a definition of a Native American term, before it moves to her last novel, Sapphira and the Slave Girl (1940), which is noted as having been criticized by Toni Morrison for its perception of blackness through the “white gaze”. Most of the text focuses on summarizing the events depicted in this novel, and offers other critical remarks on it. Then, the narrative moves on to post-Civil War politics in the West. And then the story gradually shifts to making broad guesses about what Cather’s early life might have been like, based on their being a melting pot of different nationalities like “Swedes and Danes, Norwegians and Bohemians” in these places. Such generalities really do not add anything to a reader’s understanding of an author. One of the first specifics offered is this: “Farm life in rural Webster County did not suit Charles Cather, and after eighteen months he moved his family from the Divide to Red Cloud proper.” In the latter place he started a lending, real estate and the like business, and moved away from farming. The preceding pages of this book were setting up Cather as a symbolic farmer’s daughter, who was passionate about the countryside, and now we learn that she was the daughter of a wealthy businessman, who was mostly detached from any of these rural ideals.

Chapter “Five: Breaking Free” opens with a description of where she lived in New York at this stage in her career in 1912, with her negative comments about this place to Elizabeth Sergeant. Then, there is a curious note: “She was busy throughout the summer of 1913 – the summer of her triumph with O Pioneers! – doing a large favor. She had consented to write Sam McClure’s autobiography, basing herself solely on his spoken recollections”. It was serialized in McClure and published as a book and merely included this note “from the supposed author: ‘I wish to express my indebtedness to Miss Willa Sibert Cather for her invaluable assistance in the preparation of these memoirs.’ She’d written every word of them.” Taylor appears to be acknowledging that there were no “spoken recollections” to work from, but rather that she simply ghostwrote the whole work, probably in exchange for having her first success, O Pioneers! puffed by McClure’s friends, thus generating the critical and fiscal “success” out of an exchange of ghostwriting for puffery.

While most of this book is tedious to read as it flitters on various unrelated subjects, there are clearly valuable nuggets of information scattered across it. Thus, scholars of Cather and those who merely enjoy reading her should find some curious or relevant to their own information if they read this book closely enough. There is a search option in the ebook I reviewed, so searching for specific names, places or titles of interest should be easy. This seems to be the only mention of Cather writing an “autobiography” for somebody else, and there are no usages of terms like “ghostwriter” across the book.

Pufferies of “Coleridge”, Which Are Deflated If He Merely Contracted a Ghostwriter

Tim Fulford, Ed., The New Cambridge Companion to Coleridge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023). Hardcover. 265pp. ISBN: 978-1-108-83222-9.

****

“An indispensable guide to his writing for twenty-first-century readers, it contains new perspectives that reframe his work in relation to slavery, race, war, post-traumatic stress disorder and ecological crisis. Through detailed engagement with Coleridge’s pioneering poetry, the reader is invited to explore fundamental questions on themes ranging from nature and trauma to gender and sexuality. Essays by leading Coleridge scholars analyse and render accessible his extraordinarily innovative thinking about dreams, psychoanalysis, genius and symbolism.”

After publishing my 20-volume British Renaissance Re-Attribution and Modernization series, I just finished the computational-linguistics testing of 19th century British texts that included one texts from “Samuel Coleridge”: Biographia Literaria; or, Biographical Sketches of My Literary Life and Opinions (1817). The initial finding is that Coleridge was not likely to have been the underlying ghostwriter behind this group. I also tested “Mary Elizabeth Coleridge’s” Fancy’s Guerdon (1897), and she was also not likely to be the ghostwriter behind this different linguistic group. And I tested “Samuel Coleridge’s” poetry, Lyrical Ballads: The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner (1798), separately in my 18th century study, and yet again he was not likely to be underlying ghostwriter behind the group that included his text. This first “Coleridge” text was published anonymously. It is likely that Coleridge was able to gain access to a top ghostwriter because his father was Reverend John Coleridge, the headmaster of the King’s School (a rare free grammar school); John’s early death might have solicited sympathy for him at the Christ’s Hospital charity school that he attended afterwards. Samuel was accepted into Cambridge, but never graduated (a sure sign that he was not a scholar, but rather relied on ghostwriters’ help, and did not have enough funds in an inheritance to pay for this labor to finish his education). His friend from Cambridge, Robert Southey, has a matching linguistic style to “Coleridge’s”, so the two must have met this ghostwriter at Cambridge. At this stage, I’m uncertain if Southey might have been a ghostwriter, as his biography matches a poetry-heavy group in the 19th century corpus, but does not clearly fit the timeline of the 18th century corpus that matches his linguistic style; I’ll explore this question closely when I start writing the book on these subjects. Then again, some of the early poetry collections released from these bylines were anonymous, such as the Sonnets from Various Authors (1796) collection that was initially anonymous and then was re-assigned to “Coleridge”, Southey and others. The bylines might have been sold to these “authors” after the book was puffed in the press. It is puzzling where Coleridge managed to find money for his education, these publications and other luxuries, as the source of his income after his father’s death is mysterious.

When I stumbled on this biographical question I turned to the book under review and found its chronology helpful. It explains that in 1796 Coleridge established a journal called The Watchman, and also received a job “writing for the national newspaper The Morning Chronicle”. He probably subcontracted ghostwriters to do his writing and editing for him, while he profited from selling the periodical and finding connections to help him gain these profitable positions. In 1798, his financial woes were resolved with an “annuity from the Wedgwoods, freeing him from the need to earn his living as a Unitarian minister”; the funding from this annuity would have also later sponsored his ability to place his byline on poetry books and the like. The unlikelihood of him being a real author is also stressed by him “using opium heavily” by 1801, a period when he was supposed to be actively writing “for newspapers” and on several other creative projects. I plan on returning to this book when I am writing a chapter on Coleridge to study the insights that can be gained from across its contents.

Sadly, the first chapter, from Tim Fulford, begins with an extensive puffery of “Coleridge” (though he is not named in this section) with overflows of exuberance at his “genius” from “Hazlitt’s” Lectures on the English Poets (1818). “Hazlitt” matched a different linguistic signature and was also proven not to be the underlying ghostwriter, so this puffery is really probably from a ghostwriting affiliate of “Coleridge’s” ghostwriter, who is reflecting on his literary abilities, seemingly after his death. Fulford uses this quote to support his own puffery of “Coleridge”, and adds that the archival closeted materials assigned to “Coleridge” since his death are especially “worthy of comparison with Wordsworth’s Prelude”. “Wordsworth” matched a different linguistic group from “Coleridge” and is also likely to have written his own work. Very little of what is said here would survive my re-attributions; this is because “literary autobiography” or the use of biography and cross-byline pufferies has been an enormous part of literary criticism since the British Renaissance. Instead of dissecting the elements of literary compositions, most critics use standard broad pufferies that can be applied to most authors without much deeper research. The point of literary criticism thus seems to be an advertisement of various bylines and books a publisher has for sale, instead of teaching new writers how to compose literature themselves. Fulford even adds that “Coleridge’s” Biographia (1817), which I also tested as previously noted, raised “literary criticism to a new level, essentially founding it as an intellectual discipline” (1-2). This is the central problem at issue because if ghostwriters who were self-interested in puffing or selling their different bylines and books (as opposed to inviting students to compete with them in the labor of literary creation) established this genre of “literary criticism”; then, the entire field must be overthrown and rebuilt anew for the world to progress in its ability to create original new literature (without ghostwriting assistance). Instead of noticing the significance of this point regarding “Coleridge’s” founding of the field of literary criticism, Fulford then digresses into summarizing the various broad theoretical fields that have been employed to criticize “Coleridge’s” works, such as “ecological” criticism. While it is certainly important to discuss ecology and “Cancel Culture”, isn’t the science of literary criticism itself more important than fitting very old ideas with contemporary clichés (3)?

The chapters in the rest of this book cover genres (nature lyrics), theoretical topics (politics) as well as some structural components (metres), and questions such as his “collaboration” with other writers. Felicity James’ chapter on collaboration attracted my attention, but instead of explaining the specifics of what evidence exists for how “Coleridge” collaborated, the chapter digresses into various general theories or ideas about collaboration. One quote that is curious out of these digressions is when the dedicatee, “Charles Lamb”, objects: “don’t make me ridiculous any more by terming me gentle-gentle hearted, and substitute drunken dog, ragged-head, seld-shaven, odd-ey’d, stuttering, or any other epithet which truly and properly belongs to the Gentleman in question”. This criticism probably reflects the true nature of these bylines as these people were viewed by their over-worked ghostwriters (32); “Lamb” also didn’t write his own work, and was covered by a different ghostwriter than “Coleridge”. Further into this chapter, the author digresses further and further from the point, instead making grand and nonsensical statements such as that “Coleridge’s collaborative mode moves between public and private” (34). The narrative does become interesting and focused at times, as in the explanation that in Biographia “Coleridge” “outlines ‘the plan of the ‘Lyrical Ballads’” that includes “Coleridge” splitting the work with “Wordsworth”, “so that Coleridge’s ‘endeavors should be directed to persons and characters supernatural, or at least romantic’: ‘Mr. Wordsworth on the other hand was to propose to himself as his object, to give the charm of novelty to things of every day, and to excite a feeling analogous to the supernatural’” (37). This description really uses synonyms to say that both would basically be doing the same thing, or writing about the “supernatural”; thus, the intended meaning is likely to be that despite many bylines, there was a single dominant underlying ghostwriter behind this whole composition. There must be similar revelations to be found across this collection if I dig through it diligently enough. A glance at it probably reveals the flaws of puffery, repetition and digression, while hiding most of the dense analysis and facts in these weeds.

I do my best to avoid reviewing collections of literary criticism, as the individual chapters tend to repeat many of the same pufferies about the main subject, and then addressing some of the same theoretical frameworks across its chapters (politics, gender, environment). In this sense, this book once again proved the rule that such collections are to be avoided. On the other hand, there are many archival findings, facts, and other bits of information that would be difficult for me to access otherwise, given that I do not have institutional access to major collections of books and journals. Similarly, students who are researching “Coleridge” in remote high schools or colleges, would benefit from having this information gathered in a single book that a small library might be more likely to purchase than the various sources that are cited across this collection.

Who Is Lord Byron, If Not a Writer

Drummond Bone, Ed., The Cambridge Companion to Byron (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023). Hardcover. 312pp. Chronology. ISBN: 978-0-521-78146-9.

*****

The blurb argues that “Byron’s life and work” has been of past interest, while instead “it is the complex interaction between his art and his politics, beliefs and sexuality that has attracted so many modern critics and students. In three sections devoted to the historical, textual and literary contexts of Byron’s life and times, these specially commissioned essays by a range of eminent Byron scholars provide a compelling picture of the diversity of Byron’s writings. The essays cover topics such as Byron’s interest in the East, his relationship to the publishing world, his attitudes to gender, his use of Shakespeare and eighteenth-century literature, and his acute fit in a post-modernist world.”

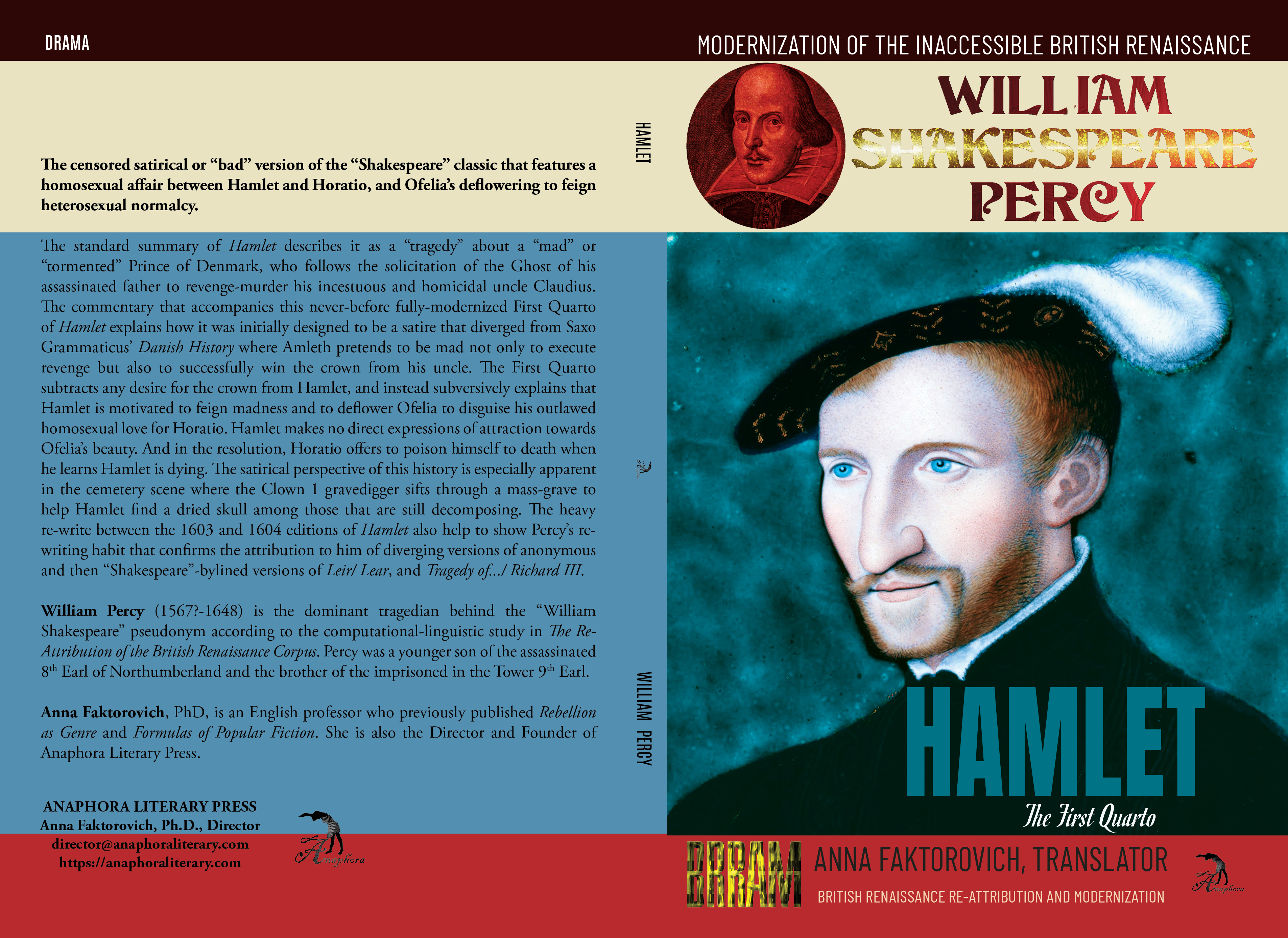

I tested two texts of “George Byron’s” poetry in my 19th century corpus, and both of them matched the same linguistic group, but “Byron” was not the underlying ghostwriter for it, but rather it was probably ghostwritten by “Coleridge’s” friend, Robert Southey, or alternatively (and more curiously) by Ann Taylor (who published children’s poetry under her own feminine byline). I have caught the passion for Byronic poetry when I was doing graduate literary studies. Byron’s biography, including his patronage of other authors, and his romantic adventures is difficult to remain dispassionate about. But when the authorial input is subtracted from this equation what remains is that Byron used literary credits to seduce women (some of whom did not survive the fall from grace) and men, and to generally live a debauched life of a powerful aristocrat. Byron was involved in the “business of publishing”, as Peter W. Graham’s chapter points out, and in the business of the theater, as Alan Richardson’s chapter notes, so he remains a curious subject for my current research from at least these perspectives.

The opening paragraph of Graham’s chapter fully grasped my interest, assuring that I will return to this book to read it closely for my study. It explains that Byron had complex relationships with publishers such as “the conservative John Murray and the radical John Hunt” (27). From my previous attribution research, I have found that legal and technical relationships with publishers frequently explain the motivations, profit-origins and various other essential points regarding how ghostwriting and contracting operated in a given age. There is also a note regarding the appearance of 17 reviews in response to “Byron’s” first self-attributed work of poetry, of which 2 were noticeably “negative”, including a joke about “this Lord’s station” (29). The negative reviews were from an obscure byline and an anonymous one. This points to a need for further exploration. Another curious point is that this first poetry collection was probably designed with a political purpose, as “suppressing the poem ingratiated Byron with Holland’s Whigs,” while also “writing and publishing it had earned him the favor of Tory readers” (30). Both of these positive outcomes were probably achieved by ghostwriters puffing Byron, in an unbelievable self-contradicting way. It is curious how modern critics still buy into these pufferies, as if they were indeed true and believable without major corruptions of the whole system.

Another chapter that drew my attention is Andrew Elfenbein’s “Byron: Gender and Sexuality”. It begins with a note that most modern critics use Byron as a positive example of poetic homoeroticism, whereas during “Byron’s lifetime” the critics of “Byron’s” poetry described it as designed “to corrupt by inflaming the mind, to seduce to the love of evil”. I doubt these views are really opposites, as back in the 19th century the threat of being seduced into evil was just as attracting to readers, as today blatantly positive obscenities are. I will explore these subjects as I consider a few different homoerotic texts from across the 19th century corpus. This chapter then dives into “Christian manliness” of texts such as the 18th century classic, “Samuel Richardson’s” Clarissa. Looking further might help me understand the clashes and matches between these different literary and gender-imagining styles.

Overall, this is a curious book that should benefit anybody who wants to dive deeper into a wide range of topics suitable for high school, college and graduate essays related to Lord Byron. So this book is a necessary one for libraries of all types.

A Rare Study of the Shunned Hack Novels of the Romantic Era

Hannah Doherty Hudson, Romantic Fiction and Literary Excess in the Minerva Press Era (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023). Hardcover. 306pp. Figures, index. ISBN: 978-1-009-32196-9.

*****

“Jane Austen’s ironic reference to ‘the trash with which the press now groans’ is only one of innumerable Romantic complaints about fiction’s newly overwhelming presence. This book draws on evidence from over one hundred Romantic novels to explore the changes in publishing, reviewing, reading, and writing that accompanied the unprecedented growth in novel publication during the Romantic period. With particular focus on the infamous Minerva Press, the most prolific fiction-producer of the age, Hannah Hudson puts its popular authors in dialogue with writers such as Walter Scott, Ann Radcliffe, Maria Edgeworth, and William Godwin. Using paratextual materials including reviews, advertisements, and authorial prefaces, this book establishes the ubiquity of Romantic anxieties about literary ‘excess’, showing how beliefs about fictional overproduction created new literary hierarchies. Ultimately, Hudson argues that this so-called excess was a driving force in fictional experimentation and the advertising and publication practices that shaped the genre’s reception.”

As I have just completed a computational-linguistic study that covered most of the canonical novels from across the 18th and 19th century, and I am about to embark on writing a book that explains my re-attribution of this “overproduction” to only 10 ghostwriters in the 18th century and 11 ghostwriters in the 19th century, I am interested in very different bits of evidence in this study than a casual reader is likely to notice. From my perspective the argument “that there were simply too many novels, that their proliferation was threatening (economically, morally, physical) and that their numbers necessitated an ongoing process of categorizing, managing, and evaluating them” is representative of the view of this small group of ghostwriters, as they were self-interested in monopolizing the press to promote their own titles, while blocking or censoring out rivals’ creations. Their echo chamber of mutual puffery or the positive criticisms and mentions they gave each other’s works, and the lack of mentions of potential rivals is what has meant that a test of canonical works across these periods matches only these few linguistic signatures. The criticisms of all novels or groups of novels by specific critics probably indicated a rivalry between ghostwriters; the novels’ ghostwriter(s) were probably making more money on churning out volumes of trash, while the underpaid scholarly critic(s) who had to puff these works as “great” literature were probably frustrated with just how few positive elements they could find to puff about.

Hudson points to Peter Garside’s The English Novel, 1770-1829: A Bibliographical Survey of Prose Fiction Published in the British Isles (Oxford University Press, 2000) that presented data that literacy rates among English readers increased in tandem with the “number of novels on the market. Hudson argues that this rise is “inseparable from the history” of “the Minerva Press” (1790-1820). William Lane began his career by selling books from “his father’s poultry shop” in the 1770s, and only founded the press in 1790. Curiously, as I searched for “Minerva”, “Lane” and his successor “A. K. Newman” in my corpuses, I did not find them (perhaps because their works were ostracized from the puffed canon of classics). Hudson calculates that Minerva’s output was “around 600 novels between 1790 and 1820” or “more than a quarter of all the new novels in England, and more than five times as many as any other single publisher during this time period”; based on Raven’s “Historical Introduction” in The Business of Books. “While in the entirety of the 1770s barely 300 novels were published in England, by the 1790s that number had more than doubled”. Given the small number of ghostwriters during these centuries, they got into the habit of using many differently named printers and booksellers on title-pages in order to avoid making their monopolization of the marketplace obvious. Any bookseller or printer who ignored this rule in the pure interest of profit would have been a rebel for the other players. Hudson’s math will be useful to me when I work to explain that I tested a significant portion of all published novels among the 632 or so texts I tested from these centuries. One of the reasons the Minerva titles are not noticeable in my corpus becomes apparent in “Chapter 1’s” section on “Authors”, which notes that “one of the earliest works published by Minerva was Laurentia (1790), which was anonymously signed as being by “Sabina”. Anonymous texts that critics have not re-assigned to a famous byline tend to be ignored by the corpus because most literary criticism is really pufferies of biographical grandeur of the “Authors” behind the texts under advertisement. Another mention is of the anonymous The Haunted Castle (1794), and Iphigenia’s (1791) authorship by “A Female Writer”. One of the few novelists mentioned by name among Minerva’s output is “Eliza Parsons”, who I did not test in my corpuses. One name that is familiar for my corpus is “Anna Maria Mackenzie”, as I tested two of “Henry Mackenzie’s” works, and it is likely that the same ghostwriter also used the “Anna Maria” byline; “Henry’s” works were sold by T. Cadell, or a mainstream bookseller. Yet other bylines I did not test are “Mary Ann Hanway”, “Eliza Sophia Tomlins”, “Regina Maria Dalton”, “William Linley”, “Francis Lathom”, “Joseph Moser”, “Henry Siddons”, and “Sarah Lansdell”; but given that Minerva produced hundreds of novels and most of them included single-novel works by unique bylines; and few of these bylines have had any biographies written about them; it is very likely that most of these names were pseudonyms that were used by perhaps one or two house ghostwriters that were employed by Minerva. One of the few authors described as an author of “more than ten Minerva” novels is “Anthony Frederick Holstein”. It is possible that this cluster of critically ignored bylines represents the true original voices of the period (whereas canonical texts were monopolized by ghostwriters); but it is absurd to assume that the most hacked or the most speedily written compositions were original, as obviously such hack-work is only likely to be worthwhile for a writerly laborer for a profit. There are few mentions across this section of who these writers were, or what they did for a living, or where they lived, so the odds that they were pseudonyms is increased by this absence. This likelihood is furthered by Hudson’s note that Something Odd! (1804) “though attributed to a woman, Mary Meeke, begins with a lengthy satirical ‘Dialogue between the Author and His Pen’”; in other words, the female byline is directly contradicted by the over-worked publisher who hacks a preface from a male pseudonym together with a title-page from a feminine pseudonym. The explanation for this overflow of bad novels is likely to be that ghostwriters submitted such attempts to different publishers, and their worst compositions floated down to the least discerning presses like Minerva, while the best ones were accepted by mainstream publishers, who had the resources to pay for pufferies to advertise these works and thus welcome them into the mainstream canon. The illusion of the quality of the canon of 18-19th century British novels is thus the result of this sifting out or non-criticism of “bad” novels, such as those released by Minerva. Hudson and other modern critics are breaking this illusion of British superiority or perfection by digging through this junk-pile. Though Hudson is clearly attempting to argue that these works by mostly “female” writers are also worthy of critical acceptance because of the deep thoughts that hide within their pages. There might indeed be treasures in this junk-pile, but entire volumes of critical analysis are necessary to explain, puff and otherwise digest any one of these texts to create the illusion that it belongs as an equal resident in the canon. I am considering adding at least a couple of these Minerva texts into my corpus to test approximately who was behind this cluster, but I’m not sure if any of these works have been digitize to allow for such testing (such a lack of digitization would explain why this group isn’t already in my corpuses). The first byline I came across of somebody I did test is one of the reviewers who analyzed these texts harshly, who “has been identified as Mary Wollstonecraft”; my tests indicated the “Wollstonecraft” used a ghostwriter, and that this ghostwriter primarily wrote non-fiction, whereas the work being criticized would have been a novel by a rival ghostwriter that specialized in hack-novels. Another byline in this text I recognized as having tested is that of “William Godwin”, which has been assigned to a novel called Imogen: A Pastoral Romance: From the Ancient British (1784; pretending to be translated from Welsh) and it was published by William Lane before he founded Minerva; according to my initial findings “Godwin” also hired a ghostwriter that specialized in non-fiction, but a different one from the one “Wollstonecraft” used. The group that includes “Godwin’s” text also includes a history of Scotland and various other regions of Britain, which fits with the interest in recovering Welsh history. It is unlikely that this ghostwriter went on to write pop novels for Minerva, but rather it is likely that Lane learned that there were small profits to be gained from “great” writing, and thus instead specialized in publishing a lot of whatever could be churned out at greater speeds. Another byline that I tested is “Elizabeth Inchbald”, whose novel fell into a different linguistic group than her play, and both indicated she was likely to have used a ghostwriter. I tested “Inchbald” because she wrote texts on “political unrest” that made them attractive to critics over the centuries. The works discussed by Hudson from “Inchbald” were not published by Minerva, but rather are used as an example of a counter-hack novel form.

Given that I gathered a great deal of curious details from this text, it is likely that miners from various scholarly fields will find something different to learn from this scholarly work. This book is suitable for academic libraries, and for scholars of this period and of novels. The author certainly put in a great deal of labor in sifting through this difficult gathering of novels that are relatively rarely discussed by anybody else.

The Problem with Nonsensical Literary Theory

Sylvie Patron; Catherine Porter, translator, The Narrator: A Problem in Narrative Theory (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2023). Hardcover. 368pp. Index. ISBN: 978-1-496231-40-6.

**

“The narrator (the answer to the question ‘who speaks in the text?’) is a commonly used notion in teaching literature and in literary criticism, even though it is the object of an ongoing debate in narrative theory. Do all fictional narratives have a narrator, or only some of them? Can narratives thus be ‘narratorless’? This question divides communicational theories (based on the communication between real or fictional narrator and narratee) and noncommunicational or poetic theories (which aim to rehabilitate the function of the author as the creator of the fictional narrative). Clarifying the notion of the narrator requires a historical and epistemological approach focused on the opposition between communicational theories of narrative in general and noncommunicational or poetic theories of the fictional narrative in particular. The Narrator offers an original and critical synthesis of the problem of the narrator in the work of narratologists and other theoreticians of narrative communication from the French, Czech, German, and American traditions and in representations of the noncommunicational theories of fictional narrative. Patron provides linguistic and pragmatic tools for interrogating the concept of the narrator based on the idea that fictional narrative has the power to signal, by specific linguistic marks, that the reader must construct a narrator; when these marks are missing, the reader is able to perceive other forms and other narrative effects, specially sought after by certain authors.”

I requested this book because a few months ago I was asked by a journal of narratology to add recent narrative theory to my essay in order for them to be able to include it. They were basically requesting that I cite essays they had previously published on the subject. I responded with questions, noting the irrelevance of this theory to my subject, and the negotiation ended there. I had reviewed some of this narrative theory during this discussion, and when I saw an entire book on the subject, I thought I should request it in case any future journals asked me to add content on this subject. However, the description of this book should have given me pause, as it blatantly explains this is one of those postmodern theory books that manage to use big words to cover up complete nonsense or scholarly double-speak circles around non-statements. The point of such books seems to be to generate hundreds of pages without saying anything of any intellectual value. Critics appear to review such works positively simply to avoid actually reading anything inside them, as negative criticism requires an excuse, while puffery can be dealt out in formulaic measures. It is even more troubling that this book’s “Introduction” begins with a negative criticism of predecessors that basically attempted the same type of nonsense about narratology that is being mimicked here. Patron states she felt compelled to write this book because she felt indignant about Gerard Genette’s Narrative Discourse Revisited, noting various mistakes in it, such as forgetting the “epistemological” or historical reflection on the longevity of the field of “narrative studies”. She objects to the citations, the construction of the argument, and the generalizations, before giving a nearly page-long quote from this text. All these critiques would be useful if Patron did not repeat all these mistakes herself. After the long quote, Patron points out that the passage’s mistakes include that the “narrator” cited in it from a fictional story is not actually a character in this story, but rather the name of a restaurant (“Henry’s”). Why would any rational theorist spend so much of the introduction on quoting and criticizing a previous critic that has written totally erroneous and nonsensical mumbling? This section concludes by Patron stressing that her own book will not be about Genette’s, and then she restates her thesis, as one that is similar to the essence of Genette’s argument. She sets out to argue about these puzzles: “(i) there is no narrative without a narrator; (ii) the narrator is an ‘I,’ either explicit or implicit; (iii) the author is real, while the narrator is fictive or fictional” (1-3). The last point is relevant to my research, as my attribution studies have discovered that biographies of too many canonical authors, such as “Shakespeare”, are as fictional as the narrators. Especially in 18th century British literature, there was a mix of books published where no author was named, while the narrator thus was presented as if he or she was the author; exploration and adventure books are especially guilty of this fault; frequently such books were later assigned separate “authors” by publishers without any evidence to prove these claims, while in other cases the publishers argued the narrators were indeed the “authors”. And indeed Patron goes on to explain in the next section on the “Traditional Concept of the Narrator” that in 1804 Anna Laetitia Barbauld argued there were “three modes for presenting and developing a story”: 1. “Narrative or epic” mode, where “the author himself relates the whole adventure”. 2. Memoirs, “where the subject of the adventures relates his own story”. 3. Epistolary novel or “epistolary correspondence, carried on between the characters of the novel”. The latter of these is the one that Samuel Richardson specialized in, on whom Barbauld was commenting in these remarks. British ghostwriters created letters assigned to “Elizabeth I” as well as other British monarchs, aristocrats, politicians and other notable people, and they published some of their two-sided correspondences as novels, as if to advertise their epistolary or secretarial skills to potential wealthy clients. Barbauld pointed out that the author’s or narrator’s “passion cooled” between the time they felt something like what is described and the time of it being written down. I tested both Barbauld and Richardson linguistically, and neither of them were the likely ghostwriters behind the texts in their linguistic groups. What “Barbauld’s” ghostwriter really meant was that a hack writer keeps rewriting similar sentiments under multiple bylines and as multiple narrators and characters, the feelings fade to nothing, but the job remains, and becomes merely a plagiarism of what was once a genuine passion. But the point Patron draws out is that even when a novel is narrated by seemingly the author or by a “third-person”, the narrator is still a fictional voice, as the narrator can be lying or skewing the story to fit some larger design of the author. In the next section Patron discusses the nineteenth century “disappearance of the author”, as the narrators seemed to lose their sense of self, but rather became engulfed in relating the actions and views without commentary with their own interpretations of these events (8). This was a trend that is still with us today, as critics favor the “objectivity” of a narrator who uses “dramatization” or portrays actions and dialogue without philosophizing about the content related. This movement towards action has meant that books have been chiseled down to skeleton story-telling, as repetitive dialogues are seemingly designed to mimic what people really say, and the lack of descriptive detail is displayed as a positive sign of attractive brevity. This has meant that there are no new “great” novels made, as it is impossible to make anything “great” without it including either characters or the narrator saying original things in new and deeper ways that reflect and philosophize on the conditions portrayed. Patron mentions this opposing perspective as having been covered in Wayne C. Booth’s The Rhetoric of Fiction (1961) that argued that the author should dare to address the reader, and to make “commentaries on and judgments of the characters” (11). The rest of this introduction reviews other main events in the early history of postmodern narrative theory.

Then, the first chapter is all about Genette, as it keeps returning to the attempt to redefine the same old concept of a “narrative”. It echoes standard definitions, quotes from synonymous echoes from critics, and keeps cycling on clarifying each of the terms in these definitions. This explanation makes the author of this criticism appear to be adding something new to the discussion by correcting mistakes this author is imagining readers are likely to be making, such as that “the narrative is always ‘uttered by someone’” (23). Readers are invited to stop and question if they have at some point doubted that a narrative is indeed related by “someone”, especially since the previous content suggested that the author or narrator has been “disappearing”.

The second and the following chapters puff specific critical bylines that are included in most literature reviews in the narratology field. The second chapter, in particular, is about Lubomir Dolezel, and a couple of his works including Narrative Modes in Czech Literature (1973). After a preamble warning regarding what Patron plans to discuss and what she plans to omit, she summarizes the simple “thesis” of Dolezel’s that there are works related by a “narrator” and others related by a “character”. This basically returns to a simple first versus third-person voice split. But then these concepts are muddled by suggesting there is a blurring between them; of course, there cannot be any work of fiction where characters’ voices are not somewhat blurred with the voices of their narrator(s).

Long before this point, most readers should have absconded out of this composition. It is incredible how I have just read dozens of pages, and yet gained nothing new from the experience aside for what I added to it, or an added understanding of how theorists compose circles of nonsense and make it sound like they are misunderstood gurus. I hope nobody attempts reading this book again, so I hope no libraries purchase it for their collections. If any new scholars are asked to add “narrative theory” to their essays, I hope they report back that all that one needs to know about the concept of the “narrator” and the “character” is found in dictionaries.

A Novel Imagining of a Goatish Ovid Rambling Around

Michael V. Solomon, The Scapegoat: Ovid’s Journey Out of Exile (Exeter: Unicorn Publishing Group, 2023). Softcover: $15. 416pp. ISBN: 978-1-911397-43-4.

**