Anna Faktorovich

“But Why?…” [Write in Your Own Reasons for Assassinations]

John Withington, Assassins’ Deeds: A History of Assassination from Ancient Egypt to the Present Day (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, December 8, 2020). Hardcover: $25. 368pp, 6X9”. 81 halftones. ISBN: 978-1-78914-351-5.

***

The other day, I looked up the tree of potential heirs who could have inherited Elizabeth I’s throne upon her death in 1603; it turned out that at least 12 of them had died young, 1 was disqualified because Elizabeth refused to acknowledge his parents had married, and 1 simply never made a claim for the throne. Instead, Mary Queen of Scot’s son James I took over both the Scottish and English thrones. This seizure of power has historically been presented as England conquering Scotland in this union of the crowns, but it was really a victory for the plot to overthrow Elizabeth and her line of succession by James, the Scottish king. If James had been second or third in line for the throne, the deaths of a dozen alternates would appear accidental enough, but surely this extraordinary number of premature deaths had to be a series of undiscovered or covert assassinations. Given the power assassinations hold in shifting international politics between political parties, between families, or between countries, the scholarly study of cases where a death is a confirmed assassination is essential for the security of the world. Can there ever be a benevolent assassination of a nuclear scientist, or a totalitarian leader? Surely, any type of assassination invites the question of why any cause is worthy of murder without the judicial punishment of the guilty assassin or the leader ordering the hit. Thus, this book sets out on the honorable quest of explaining the crime of assassination in its widely different geographical and political contexts.

“Personal ambition, revenge, and anger have encouraged many to violent deeds, like the Turkish sultan who had nineteen of his brothers strangled or the bodyguards who murdered a dozen Roman emperors. More recently have come new motives like religious and political fanaticism, revolution and liberation, with governments also getting in on the act, while many victims seem to have been surprisingly careless: Abraham Lincoln was killed after letting his bodyguard go for a drink. So, do assassinations work?” This is a curious scholarly question that I have not seen addressed from this perspective before. The book not only reviews the “historical evidence” but also the “statistical analysis” to understand the aftermath of these assassinations. This history is just as concerned with describing “ingenious methods of killing”, as the “many unintended consequences.”

The book is divided into chapters by the ages that held different perspectives on assassinations, relations and murder. For example, in the “Age of Chivalry”, duels for love or against offenses were considered honorable and required of nobility. Meanwhile, during the “Wars of Religion”, killing over religious convictions became honorable. And in the “Age of Revolution”, killing to prevent tyrannical monarchs from having power over the people became socially acceptable. And now in the modern age, assassinating those the media classifies as “evil” such as the Nazis and terrorists has become a new noble unpunished quest. The final chapter addresses the assassinations that have gone unpunished in contrast with most of the others that have tended to lend to the execution of the assassin if he or she acted without state-authorization.

The opening pages of the “Prologue” are somewhat disappointing as John Withington repeats a fictitious scene with gestures such as “leaps”, thoughts regarding what to do next, and various other dramatic details that are indeed entirely fictional as they paraphrase the 1927 assassination by a Chinese revolutionary in Shanghai that was created by Andre Malraux for his novel, La Condition Humaine (1933). Withington then explains that real assassinations do not come with the “novelist’s all-seeing eye”. The opening would have been stronger if it opened with a quote from one of the more detailed confessions of an assassin regarding how he proceeded in his or her deed. In reading of the archives, interrogation and confession files tend to be far more emotionally-triggering in their striking details than any cliché motions that repeat across novels that describe formulaic assassins. The rest of the “Prologue” stops to question what distinguishes assassinations from regular “murder” and uses the dictionaries to explain that assassinations are murders of the “famous or important”, or one that is performed with a “political or ideological motive”.

The book picks up speed and focuses closely on the facts starting with the first chapter. “The Ancient World” chapter opens with the “‘first known victim of assassination’”, or the “Egyptian pharaoh… Teti…” who was “‘murdered by his bodyguards’”. Withington notices that this is only a potential assassination because it was first claimed as such 2,000 years later in Manetho’s account. However, the case is handled largely with questions of whodunnit, instead of providing evidence for each potential murderer. In one sentence Withington writes: “We know that he was succeeded for a short time by a man named Userkare.” There are no notes or citations in this entire paragraph about this assassination. This sentence and others give the impression that historians have previously determined the specific length of time for which “Userkare” ruled, but this information is kept out because it is boring to Withington or he imagines would be boring for readers. From my perspective, it’s not useful for my research to read generalizations such as this, as I would need to know the precise details if I was going to benefit by incorporating this narrative into a novel of my own (building over the known facts), or if I needed to quote a passage of precise history to support an argument I was making.

Similar casual language, digressions and impression is the style that repeats across the book. I am particularly interested at this time in “chivalry” because I’m studying the period in Europe that followed it, and the manner in which European monarchs outlawed honor-duels. Yet when I turned to this chapter, I found this sentence: “Almost immediately, Becket went spectacularly native” (91). This sentence includes a rather offensive descriptor joined with a serious of generalizations. From there the paragraph is full of questions such as “But why?” I’m reading this book because I need answers to these types of speculations, rather than to hear the author pondering aloud instead of doing the work/research needed to present the answer. A few pages later, Withington is pondering if “Becket might have felt less insulted”, and if the assassination was a “great career move”.

In summary, the premise behind this book is fantastic, and promises to deliver a moral, philosophical and legal treatise that accuses world history of condoning some political or famous murders, while executing others. It promises to derive the statistic and historical motives and other patterns behind the assassin’s profession. However, the execution is absolutely awfully done. This book is unreadable for scholars. Only somebody who is accustomed to reading fiction might accept these uncertainties and emotional triggers are suitable and might manage to read this book cover-to-cover. The only reason for these mistakes I can imagine is if the point is to drive a scholar reading this book into homicidal rage as he or she corrects the missing citations and the horrid digressions; and thus, by experiencing the fury of the assassin, the scholar will enter their mind in their imagination. So, unless you are searching for the most frustrating book of the year to rage against as a critic, try to avoid reading this book.

Vivid and Intellectual Narratives of the Evils that Force Migration

Ai Weiwei, Human Flow: Stories from the Global Refugee Crisis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, December 1, 2020). Hardcover: $29.95. 400pp, 6X9”. ISBN: 978-0-691-207049.

*****

“In the course of making Human Flow, his epic feature documentary about the global refugee crisis, the artist Ai Weiwei and his collaborators interviewed more than 600 refugees, aid workers, politicians, activists, doctors, and local authorities in twenty-three countries around the world. A handful of those interviews were included in the film. This book presents one hundred of these conversations in their entirety, providing compelling first-person stories of the lives of those affected by the crisis and those on the front lines of working to address its immense challenges.” The book presents condensed stories about “migrating across borders, living in refugee camps, and struggling to rebuild their lives in unfamiliar and uncertain surroundings. They talk about the dire circumstances that drove them to migrate, whether war, famine, or persecution”. It is illustrated “with photographs taken by Ai Weiwei while filming Human Flow”.

I have previously reviewed many horridly done interview books, where those being interviewed digress to repeat the same general ideas about scriptwriting or about fighting in war or other shared experiences in a manner that fails to give either researchers or those who want to imitate their behaviors or professions useful material. In contrast with these many past failures I have covered, the editors of this book have succeeded in speaking with intellectual refugees who are knowledgeable enough and interesting enough because of their outlier experiences for them all to present new perspectives and information that is essential to understand this international subject. The photographs included are also not designed to solicit donations by showing extreme desperation, but rather show the vibrant minds and emotionally complex people that are suffering among the refugees. One photo from the “Cem Terzi, Makeshift Camp” in Turkey in 2016, shows two men, two girls a woman, and a doctor tending to another child, as the others study the problem with concern. They are sitting on a carpet, wearing jeans, and some are sitting cross-legged. There are so many details, the reader truly feels welcomed into this reality, instead of feeling as if a propagandistic version of reality is being sold (114). Another photo is of a makeshift camp in Greece in 2016. The angle is of numerous tents, with lines of drying clothing at the forefront. It is clear that Weiwei truly visited these places and just took photos of what he saw and spoke with those he encountered with his full concentration and at a rapid speed that captured the reality of these moments (50).

The comments made by these refugees are uncensored. Hagai El-ad in Jerusalem, Israel in 2016 describes how he feels that Israel’s “military rule” over Palestinians is undemocratic, as they are denied participation in the political process. From his perspective, Israeli Jews have been benefiting from Europeans favoring the “Judeo-Christian” position against “Islamic extremism and terrorism”; whereas, the non-temporary occupation of the Palestinians’ land is from their view a violation of their human rights (197-8). He explains that the problem is not theological, but rather financial and practical as the Israelis practice “demolitions” or bulldozing of people’s homes, so that people are in “constant fear” of losing their possessions, and the encroaching entity has “legal excuses” for these thefts or for refusing to connect a village to utilities. At the end of this interview, Hagai accepts the offer to have another drink, so this openness comes slightly out of uninhibited inebriation; though perhaps the drink is of water… (205). Overall, this is one of the more enlightening takes on the problem of Palestinian-Israeli relations I have previously read. I am familiar with the Zionist perspective from attending Hassidic schooling, but this doctrine forces an ideological veil over a conflict that is robbing the local people. I was just reading earlier today about how Catholics’ land and houses were confiscating during Elizabeth I and James I’s reigns and granted frequently to other Catholics who were bribing or otherwise corrupting the political system. The confiscations were sold as purifying and religious measures, but these hyper-moralizing ideas were disguising outright theft of estates and fortunes won by industrious labor, and granting these riches to idiots who managed to bribe idiotic officials. This is precisely why this is a necessary book. Politicians and broadcasters should stop philosophizing about conflicts such as this Israeli-Palestinian clash, and instead listen to and look at the documented evidence presented by any party who has been violated. There is a legal and financial solution (instead of a violent military solution) to this conflict if the fraudsters are not allowed to sway by emotion and religious doctrine and instead are forced to present the facts of their case.

The other stories are similarly revealing, as Mohammad, a refugee in Berlin, describes the financial struggles he underwent during his migration (256). There are no questions asked in another section, where Rafik Ustaz, an activist in Malaysia, just relates his story and challenges without interjections. He explains: “My parents’ family was killed by the military junta of Myanmar, and our villages were burned in 1982 and 1983.” Despite these extreme hardships, Ustaz became a teacher because his community was in desperate need for basic literacy and knowledge. He gradually transitioned to helping others by working for humanitarian organizations to help people access food, medicine and other necessities (283-7).

There are no boring or irrelevant words or sentences across the pages I reviewed in this book. Each of these refugees is motivated by their own and their fellow refugees’ desperate situations to speak with succinct purpose to communicate the raw experiences they have been facing that are glossed over in cliches in mainstream accounts that stop at portraying tents or thin refugees without really asking what criminal misdeeds forced their migrations, and how they have managed to overcome and to survive these extraordinary quests. These are such captivating stories that Weiwei only took up half-a-page in his “Introduction” and another half-a-page for a photo of himself in Greece looking out into the ocean. I have previously seen a couple of documentaries about Weiwei, but this book displays his uniquely researched awareness of this problem that is apparent in the complex questions, and follow-ups that he asks in each of these foreign places. This is a much more useful endeavor for an activist versus marching because a crowd marching and chanting a single phrase is nonsensical in comparison with allowing those harmed by conflict and other human evils to express their sorrows and to call out for the unique type of help that can solve their precise obstacles.

The Philosophy and Drama of Pontano, an Early Modern European Teacher

Giovanni Gioviano Pontano; Julia Haig Gaisser, editor and translator, Dialogues: Volumes 2 and 3 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020). Hardcover. 464pp/ 264pp. ISBN: 978-0-674-23718-6/ 978-0-674-24846-5.

*****

These two volumes represent these texts first translations into English, so they are of interest to all generalist scholars of philosophical international thought. “Giovanni Gioviano Pontano (1429-1503) served five kings of Naples as a courtier, official, and diplomat, and earned even greater fame as a scholar, prose author, and poet.” Dialogues cover “religion, philosophy, and literature, as well as in everyday life in fifteenth-century Naples.” They describe Pontano’s “humanist academy over which he presided from around 1471 until shortly before his death.”

Volume 2 is Actius, “named for one of its principal speakers, the great Neo-Latin poet Jacopo Sannazaro, and contains a perceptive treatment of poetic rhythm, the first full treatment of the Latin hexameter in the history of philology. The dialogue continues with a discussion of style and method in history writing, a landmark in the history of historiography.”

The “Introduction” explains that Pontano joined the court of a Naples king at eighteen and served several subsequent kings as an adviser, researcher and overall secret-secretary. Similarly to Socrates and various other philosophers before him, Pontano had a following that became known after his death as the Academia Pontaniana. The five dialogues gathered in this Harvard edition make up most of Pontano’s original work, whereas most of the rest of his efforts were scholarly editions, transcriptions, histories and political or propagandistic treatises. The three dialogues in these two volumes were all published after Pontano’s death by his group.

Actius opens with an absurd discussion on the linguistic usage of “posterity” as it relates to the “posterior” in reference to the purchase of a cottage (3). The discussion becomes more interesting as Caeparius dives into a long monologue where he explains the sound construction of a cottage: “without any problem of water dripping from the eaves or of being used as a latrine” (5). These types of details should be useful for historians of these centuries who otherwise have few precise construction-method descriptions to rely on to make precise estimates on what life was like. Many sections of this text digress into random subjects, and leap between subjects in a manner that is difficult to follow. There are also many quotes from ancient classics, so that at one point one of the speakers, Compatre, satirizes the over-usage of these references to classics by noting that Paolo tends to “regurgitate one line of Terence and another from Cicero: ‘I am full of cracks’ and ‘not rich but full of loyalty.’ And add: ‘the world if full of fools.’” Sadly, Paolo refrains from answering the question about the preponderance of stupidity among humans, and instead inserts an avalanche of new quotes from the classics, so that Compatre gives up on returning to his initial question (29-31). The over-citation is overdone when Azio takes over and commences on a monologue lecture that takes up half of the book, across which there is basically a single speaker without interruptions. Azio begins by promising to explain the workings of merchants as well as “poetic rhythm” (103). Each of these subjects would have been better-served if it had been handled in a separate essay or speech dedicated to it. These dialogues appear to be transcribed lectures on random subjects that were taped together. There are some page-long quotes from Virgil on ancient mythology (109). And there are pages that include a dozen one-line quotes from different texts such as Aeneid and Georgics. These examples are used to generally show that Virgil and the Greek language include rhythm, counted syllables, and other tactics that were popular in Pontano’s time (139). Praise of these classics is mixed with explanations regarding the types of writing that appeals to readers: “just as a juxtaposition of syllables is pleasing because of the clapping of the same letters, so too and much more pleasing is a juxtaposition of the same vowels, since from this clapping of unelided vowels arises a great addition to euphony” (171). Thus, this dialogue needs the same type of scholarly digestion and separation of it into distinct arguments and lectures that has been applied to Plato/Aristotle and other mainstream philosophers. Their original lectures might have been as jumbled as Pontano’s but over the millennia scholars have separated them into smaller chunks on distinct topics that can be read by those researching something specific. Without this scholarly digestion, a reader has to read the classics Pontano is alluding to, and become an expert in this history and politics of this region and period before they can begin to slowly research each sentence before the next sentence takes them on a different research quest.

Volume 3 covers the last two of the five surviving dialogues—Aegidius and Asinus. Aegidius is “named for the Augustinian theologian Giles of Viterbo,” and covers “creation, dreams, free will, the immortality of the soul, the relation between heaven and earth, language, astrology, and mysticism. The Asinus is less a dialogue than a fantastical autobiographical comedy in which Pontano himself is represented as having gone mad and fallen in love with an ass.”

Aegidius opens as a group enters a house, studies it, studies the fruits and wine being served before settling to listen to the lecture. Then, Pontano praises the grandeur of the “Muses”, before Suardino breaks into tears at their repeat mentions. Suardino explains that he is thinking of the “Christian Muses” and “shrines of the saints”. Pontano tells him not to be sad but to also find joy in the “celestial Muses” that are consistent with Christian piousness (11). In another section Elio lectures on the similarity between “workmen” who “dig” a field for an employer with those who work on their souls for God to gain access to Elysium. God is equated with a “head of household in hiring workmen… for he provides them with a tool to dig and make it clear what he wants the workers to do… after the work is completed, he gives each one his wages and praises the service of those who performed the task well, but those who did badly he removes from payment and visits with disgrace” (57). Overall, these dialogues thus are attempting the revived classical philosophy while fitting it with the Christian doctrine and theology. Pontano is also trying to fit these theological ideas with the economic realities of serfdom and the first roots of capitalism springing in Europe. The employer is equated with God as laborers are taught to perform for free or for little extraordinary work at the risk of going to hell if they fall short of meeting set expectations.

While the other two “dialogues” in these two volumes are basically digressive school lectures, Asinus includes satirical dramatic exchanges that are designed purely for entertainment, and need to be acted out as a drama, rather than being read as information-buckets. In one line, Pardo exclaims: “The ass farts, we explode” (157). In one of the longer passages, Pontanus pushes the ass away as the ass is biting his hands, and tossing him into the mud. He concludes that there is no point in trying to wash an ass, as it will remain dirty, so that “my effort and expense were wasted” (165). A close reading of this drama is necessary to come to understanding of the intended meaning, the allusions, implications, and the details it reveals about Naples’ people and leaders.

This book is ideal for scholars of the time and place in which Pontano was writing. It should not be studied in general philosophy or drama courses because the topics are too intricate to be instantly grasped without preceding study of the sub-topics. Meanwhile, scholars who are focused on this type of literature will find a trove of never-before examined in English content in these pages, which can be approached from a myriad of critical approaches. Thus, all major academic libraries should carry a copy of this book, to allow those who need it or are curious about it to browse its pages for revelations.

A Refined Translation of “Homeric” Hymns

Homer; Apostolos N. Athanassakis, Translator and Introducer, The Homeric Hymns, Third Edition (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020). Softcover. 116pp. ISBN: 978-1-4214-3860-3.

*****

Unlike Homer’s lengthy and repetitive Iliad and Odyssey, these short poetic hymns succinctly summarize the Greek mythologies about gods such as Apollon, Aphrodite and Athena. The style of a mixture of allusions to mythological characters and moral lessons in these hymns includes formulaic elements that were mimicked across the European Renaissance in verse. The hymns have not been as commonly quoted as Homer’s epic works, but the lessons in poetic structure and narrative in them are more relevant for modern writers who are striving to achieve poetic heights.

This is the third edition of these Homeric Hymns, so any glitches or confusions in earlier attempts have been ironed out. The “Introduction” has been expanded and notes have been updated. This “Introduction” addresses the question of authorship. It explains that in medieval times, some of these hymns were published alongside with “Homer’s” Odyssey and Iliad in collections such as the edition princeps in Florence by Demetrios Chalcocondyles (1488). However, centuries earlier, Athenaeus had questioned “Homer’s” authorship of these hymns, instead proposing “Hymn of Apollon” was the work of Homeridae, a poet who imitated “Homer’s” style. The non-Homeric influences of later generations adding and altering these hymns as scattered pieces were transcribed for new religions is apparent in elements such as the mention of “archangel Michael”, mixed together with Hades and souls in the netherworld. I recently reviewed another book that explains that the Odyssey and Iliad are also not likely to have been written by “Homer”. I can write a book on this subject, but I am going to refrain from following this digression. If anybody is curious about the subject, this might be the reason you might pick up a copy of this book to research it further. The cover blurb acknowledges that: “these prooimia, or preludes, were actually composed by various poets over centuries.”

New students of the subjects covered in these hymns are likely to be able to understand the rudiments because the book is accompanied by tools such as diagrams of the genealogy of the Greek Gods, a map of the ancient world, and explanations of how this mythology and literary style fits with other genres. The detailed notes also explain the myths that are abbreviated in the poetry. The newly added “Index” is useful for those researching a specific Greek deity or idea.

The publisher explains these hymns “were performed at religious festivals as entertainment meant to stir up enthusiasm for far more ambitious compositions that followed them, namely the Iliad and Odyssey. Each of the thirty-three poems is written in honor of a Greek god or goddess.” Apostolos Athanassakis “preserves” most of the essential elements of this “ancient text while modernizing traditional renditions of certain epithets and formulaic phrases. He avoids lengthening or truncating lines, thereby crafting a symmetrical text, and makes an effort to keep to an iambic flow without sacrificing accuracy… Numerous additions to the notes, reflecting over twenty-five years of scholarship, draw on modern anthropological and archaeological research to explore prominent themes and religious syncretism within the poems.”

One hymn “To Dionysos” includes an absurd tale about Dionysos playing a trick by turning into a lion and then making a bear appear: “The bear reared with fury and the lion scowled dreadfully on the topmost bench. The crew hastened in fear to the stern/ and stood dumbfounded round the helmsman…” (49).

The short hymns are more focused on glorifying a god such as Zeus as “the greatest of gods” (54). A hymn “To Demeter” discusses the goddess’ virginity, the traditional roles of husbands and wives, child-rearing, and the beauty of meadows and hair (5).

Overall, these hymns are a good place for a student of ancient verse to start their studies to become familiar with these gods and their celebration before diving into denser and more digressive epics. If a library does not already have an earlier edition of this collection, this is a great time to acquire this new edition.

The Propaganda That Shaped the Maps of the “New” World

Alida C. Metcalf, Mapping an Atlantic World, Circa 1500 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020). Hardcover. 224pp, 6X9”. ISBN: 978-1-4214-3852-8.

*****

“Beginning around 1500, in the decades following Columbus’s voyages, the Atlantic Ocean moved from the periphery to the center on European world maps. This brief but highly significant moment in early modern European history marks not only a paradigm shift in how the world was mapped but also the opening of what historians call the Atlantic World. But how did sixteenth-century chartmakers and mapmakers begin to conceptualize—and present to the public—an interconnected Atlantic World that was open and navigable, in comparison to the mysterious ocean that had blocked off the Western hemisphere before Columbus’s exploration?” The covered maps “depict trade, colonization, evangelism, and the movement of peoples”. Alida Metcalf combines “historical cartography and Atlantic history” to explain “why Renaissance cosmographers first incorporated sailing charts into their maps and began to reject classical models for mapping the world… The visual imagery on Atlantic maps—which featured decorative compass roses, animals, landscapes, and native peoples—communicated the accessibility of distant places with valuable commodities.” In other words, the cartographers developed propagandistic maps that were designed to advertise world-travel to traders as an easy pathway to riches. As new parts of the globe were explored and “maps became outdated quickly… new mapmakers copied” or plagiarized predecessors’ “imagery”. This is a history of the hidden relationship between this age’s “small cadre of explorers and a wider class of cartographers, chartmakers, cosmographers, and artists”.

The reproductions of maps and segments across this book are chosen to prove specific points, rather than for their beauty. For example, three images of parrots (employed to “signify Brazil”) are used to show how later cartographers copied earlier versions of one of these parrots with increasingly less detail between a 1502, 1506 and a 1507 map (95).

The “Introduction” further explains that the “Atlantic World” appeared on a European map for the first time in precisely 1500. “Chapter One” clarifies that there had been references to the “Atlantic Ocean” more generally since the “ancient Greeks”; there was just a blind-spot in ancient maps where the world was thought to end because nobody had explored or mapped the rest of this ocean. Metcalf adds that the ancient maps themselves have been lost, so how this region was portrayed in these times has to be reconstructed from its descriptions in books. Metcalf shows the age of exploration in a new light. The journey across the Atlantic was extremely difficult, and the death-rate from diseases and war among the colonists was hardly a selling-point, but elements in these wealth-advertising maps made the journey appear to be child’s play, and kept explorers on the road across the Atlantic Ocean across the following centuries. Metcalf also views these maps from the perspectives of the slaves and slave traders, food merchants, and how information in maps was either privileged or excluded to meet political propagandistic or strategic aims of the monarchs sponsoring expeditions.

This book is saturated with informative explanations on history, cartography and other fields. For example, one section explains that the addition of “invisible circles and decorative compass roses” changed by 1502 in a manner that was previously rare, but has since been repeated through modern maps as if it is an essential element (51-2). Metcalf explains how trees and forests were sold and romanticized as detailed drawings of trees turned into more abstract images or into simply the color green (100-2). He also explains how chart makers’ insertion of cannibals into their maps solidified the claims of people-eating as a fact about native populations (115). The images of animals and other symbols on maps are explained as “visual codes” designed with specific intended meanings and messages. He describes the process of how prints and book were made between the artisans and their guilds, to the book makers and patrons that contributed to this process (107).

This book dives into many different fields and subjects as it explores new ways of seeing the maps that many of us glimpse in textbooks and assume are fixed artistic or political statements. Those who have been studying the small details in maps that reveal history-shaping points will find much to learn from in this book. Libraries from high school to public to college should have a copy of this book in case somebody wants to present a unique take on the idea of “exploration” or colonialism that reconsiders not only the significance of “Columbus” contributions, but also the manner in which these apparent achievements continue to be sold to the world’s students.

Between the Land and Sea: A Brilliant Scientific Study of Mercurial Animals

Glynnis A. Hood; Meaghan Brierley, Illustrator, Semi-Aquatic Mammals: Ecology and Biology (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020). Hardcover. 470pp, 6X9”. ISBN: 978-1-4214-3880-1.

*****

While I have reviewed a few previous animal species books, this one is unique in the relatively small number of illustrations and photographs accompanying the text. Unlike typical brief reviews of different characteristics of regional variations on a species, or brisk summaries of a species mating and eating habits, this is an in-depth study of 140 semi-aquatic freshwater mammals as a group.

The blurb explains that this book focuses on “their biology, behavior, and conservation. Semi-aquatic mammals are some of the rarest and most endangered mammals on earth. What binds them together in the minds of biologists, despite their diverse taxa and body forms, are evolutionary traits that allow them to succeed in two worlds—spending some time on land and some in the water… Covering millions of years, Hood’s exploration begins with the extinct otter-like Buxolestes and extends to consider the geographical, physical, behavioral, and reproductive traits of its present-day counterparts. Hood explains how semi-aquatic mammals are able to navigate a viscous environment with almost no resistance to heat loss, reveals how they maintain the physical skills necessary to avoid predation and counter a more thermally changeable environment, and describes the array of adaptations that facilitate success in their multifaceted habitats.” Curiosities described include: “the ‘paradoxical platypus,’ an Australian egg-laying monotreme that detects prey through electroreception; the swamps and mangroves of Southeast Asia, where fishing cats wave their paws above the water’s surface to lure prey; the streams and lakes of South America, where the female water opossum uses its backward-facing pouch to keep her babies warm during deep dives; species that engineer freshwater habitats into more productive and complex systems, including North American beavers and Africa’s common hippopotamus.” Overall, this book is designed for biologists, ecologists, environmentalists, and the less scientifically minded who are just curious to discover the alien creatures that need our protection to preserve their unique contributions to our world.

The book is divided into sections by fields of study. The extended “Introduction” defines this group, its sub-orders and otherwise explain why this is a curious subject. Part I explains “geographical” differences and habits with chapters on paleobiology, continental differences, and ecological specializations. Part II describes the odd “Physical Adaptations” of these bi-habitat species (land and water), with reviews of their morphology, physiology, and even locomotion and buoyancy (a hard science or physics approach to a mammal). Apar III covers feeding, Part IV reproduction and Part V conservation approaches.

The included diagrams are uniquely designed to explain complex topics in the text, rather than acting as pretty illustrations to catch the eye. For example, Figure 7.7 shows the difference between a bipedal pelvic and pectoral “swimming modes of beaver…, water opossum…, and platypus” from M. Brierley. Each of these animals is shown making these unique stroke patterns (229).

Every page I glimpsed includes interesting and informative details. For example, the “creek groove-toothed swamp rat” is described as having a burrowing strategy that is less aggressive than the intense “African marsh rat”. The latter “heavyset rodent” burrows up to “20 cm deep” and aboveground “build a domed nest that immediately links to a subterranean refuge burrow, which then leads directly to stream. They also have a surface entrance to the nest and distinct runways leading from their feeding areas” (119). I have never read a description this detailed of a rat’s construction patterns. I think that if mainstream television more regularly showcased these types of unique structures, people would have an easier time going vegan or supporting animal preservation. It is easier to destroy life if it can be perceived as closer in intellect to grass than to humans, but if a rat can build a more complex house than most humans can…

This book also presents a range of studies that have observed non-typical behaviors in some groups. It has always shocked me that any animal species can exhibit any similar habits to their related species on other continents. Hood mentions for example, “there is plasticity in mating strategies, with other populations of muskrats following a polygynous mating system rather than monogamy”, according to a study by Caley from 1987 (297).

Key terms throughout are presented in bold with definitions, so this book is designed as a textbook for an advanced class that intersects these fields. When Hood is uncertain about extinct species, these uncertainties are worded as such, instead of being presented as scientific facts. For example, the dinocephalian Moschops capensis is explained to have a name that means “terrible head”, and its head is believed to be “at an angle that suggests semi-aquatic behavior, much like today’s hippopotamus” (44).

A single paragraph manages to explain how these animals face more dangerous winters because they can face “excessive heat loss” in icy water, and thus need “waterproof fur” or when “trapped air is displaced in water as water compresses the pelage” to avoid hypothermia (124).

Anybody from a medical student to a conservationist should just enjoy reading this book cover-to-cover to learn bits of information that would be extremely difficult to gather through individual research of these spread-out topics. The writing style is condensed and intense without adding any information that is irrelevant or digressive. The sections are so well organized that a researcher can find a specific subject that interests them, or take some time to just enjoy reading about strange and fantastic lifeforms inhabiting our little world. Humans’ species ancestors were once living in the ocean before they became semi-aquatic like these animals. Thus, this semi-aquatic state is essential for humans to understand themselves, so the extinction of any of these in-between land-and-sea creatures is a loss that should interest even the most self-consumed among us humans.

Did Caravaggio Copy Himself?

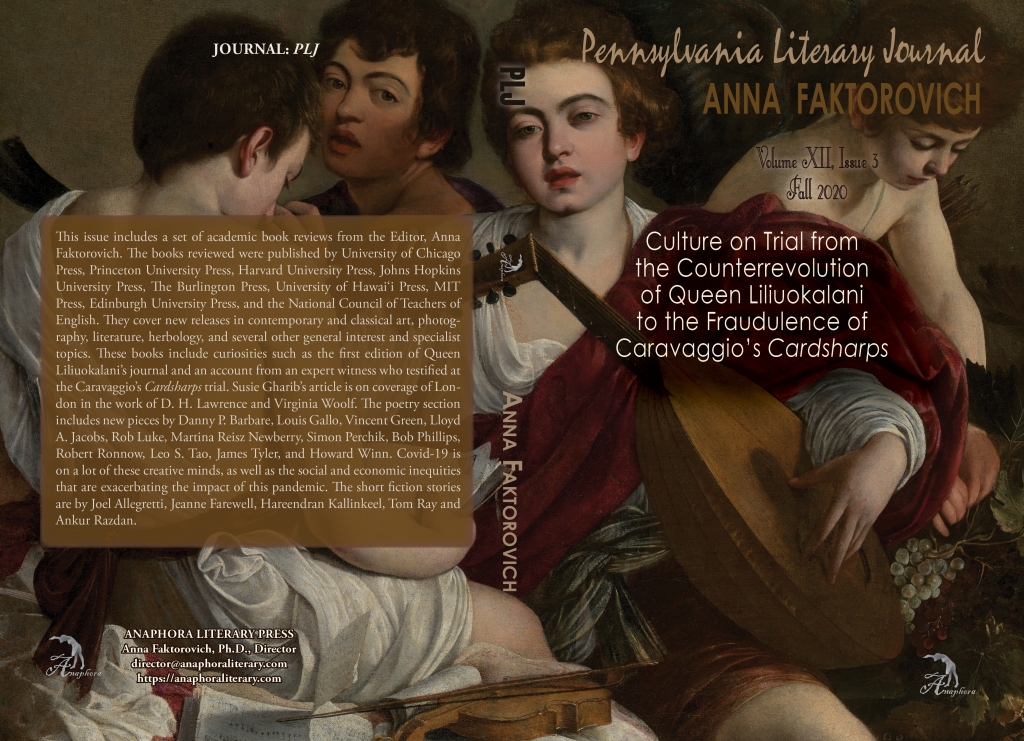

Richard E. Spear, Caravaggio’s Cardsharps on Trial (London: The Burlington Press, 2020). Hardcover. 384pp, 6X9”. ISBN: 1916237819.

*****

This book should be more engaging to readers than murder or suspense mystery novels that describe art heists or art mysteries because it provides the transcript of a trial with legal commentary and details that explain the elements of art dealing and creation that are rarely present this bluntly. The publisher explains it as an “account of Thwaytes v. Sotheby’s—one of the major art trials of recent times—will be of interest to dealers, conservators, and lawyers as well as all admirers of Caravaggio. In 2006, a Caravaggio scholar bought a version of the painter’s famous Cardsharps at Sotheby’s in London for just fifty thousand pounds. He then announced the piece was not a replica, as Sotheby’s had stated, but was in fact Caravaggio’s first version of the masterpiece—potentially worth up to fifty million pounds. Shocked by the news, Lancelot Thwaytes, who had consigned the painting to Sotheby’s, sued the auction house for negligence, and the case came to trial at the High Court in London in 2014.” The author, Richard E. Spear was called as an “expert witness in the case” because he is an “eminent art historian”. “The verdict” has tilted “the art world”. At its core the trial asked a question that should have been answered centuries ago, “whether or not Caravaggio made replicas of his own paintings”.

The book is printed on museum-quality thick paper, and the images of the painting-in-question, scans of it, and related paintings are reproduced in a quality that rivals some of the best art books I have reviewed. The close-ups in Figure 35 shows the slight variations between the “Kimbell and Mahon” versions of this painting show that they can be easily distinguished, s if the artist was drawing slightly different positions, and clothing styles, as well as using slightly different stroke patterns, and even moods between the two. Obviously, the second painting was not designed as a forgery meant to fool viewers into thinking it was the original. These types of details would make great material for an art forgery class (to explain the errors a forger can make that makes distinction easy).

The book is divided into sections that explain the background in Part I, including “Caravaggiomania”, or the various fan-art reproductions that have been made to capitalize on Caravaggio’s fame. Part II explains the “Issues”, including how this debate fits into art history, the technical issues, and the practices of auctioneering that leave room for these types of mistakes or deliberate price-inflations or deflations. Part III presents the transcript of the trial, with the opening submission of evidence, the five “factual witnesses” that described the facts of what took place surrounding the auction, and various expert witness testimonies. Part IV presents and dissects the verdict. Appendix I presents a curious excerpt from the author’s own “Expert Report” wherein he describes his relevant experience as an art historian in general, with Caravaggio in particular, and with the study of conservation. He explains his background in laboratories, examining the technical and historical elements that separate copies from originals from other types of art imitations and originals. It is very unusual for an expert witness to write a book about his own testimony at a trial such as this one, but really these experts should write a lot more books about how they reach these types of decisions because this allows future experts to learn from these examples. And if anybody has doubts about the presented expert opinions or their potential biases, now these opinions have been solidified into this extensive book that can be closely scrutinized.

The chapter on “Technical Issues” opens by explaining that Glanville used a tactic of overwhelming the judge with technical details by providing not only 129 pages of textual evidence but also oddly failing to number 350 images used in support of this text. Also, apparently the researcher had failed to study the “specific pigments” in the potential original work of art. Spear argues pigment analysis in general cannot prove “authorship”, but rather only the “date and region” of creation. Sotheby’s X-rays are questioned, in contrast with more complex tests that could have been applied. The quality of the “Mahon” restoration is also considered as a contributor to the misunderstanding. Spear argued that the “Mahon” painting lacked “searching brushwork…, indecision…, corrections” that would have occurred if it was an original rather than a reproduction (86-9).

It is tempting for me read this entire book closely because it describes art attribution strategies and I am currently working on applying my 27-test computational-linguistics authorial attribution method to texts. The spectrum of ideas Spear presents for artistic attribution shows that there are many concepts that have been explored by art scientists and historians. However, it is odd that art attribution has not been simplified to a more consistent series of tests similar to my own linguistic tests. In one section Spear argues that pigment cannot be used to determine the author, but in another he argues that heavy use of white pigment is typical for Caravaggio’s youth paintings. While some of the Renaissance texts I’m studying a worth a few thousand or “Shakespeare’s” folio might have been sold for a few million, each of these Caravaggio paintings are worth many millions, so the attribution of the entire Caravaggio corpus is worth billions. It is strange that investors buying and selling these paintings are content with uncertainties that need to be decided by a judge/ jury without technical knowledge in this field, instead of by a scientific method by major sellers/ buyers hiring a lab of experts with a series of steps to perform to arrive at decisions that are consistent and replicable, rather than mysterious and based on theories that are revealed in dribbles in complex studies such as this book.

Disclosure of attribution methodologies is the first step to solving the problems of fraud and mis-attribution in the art world, so this is a great step in this direction. All art historians and others connected to this enormous industry should read this book cover-to-cover to understand the challenges that complicate detached and unbiased distinction between originals and fakes. All sorts of libraries, scholars, and textbook searchers can benefit from acquiring this thorough first-person study into their collection.

If You Buy That This Is Art, I Have a Bridge to Sell to You

Hal Foster, Brutal Aesthetics: Dubuffet, Bataille, Jorn, Paolozzi, Oldenburg (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020). Hardcover. 286pp. 141 color and 41 black-and-white illustrations. ISBN: 978-0-691-20260-0.

**

Across my graduate studies, I tended to contemplate modern art with respect. Perhaps, it is an exploration of innovative new ideas about what art could become, I pondered. But, between the first art classes I took in the 1990s and the present, the “concept” of “modern art” has remained stagnated, as current artists are replicating the abstractions, childish doodles, geometric simplicities, paint splatters, and other tricks that appeared innovative a century ago, as if they are contributing to a continuing revolution, when they are really perpetrating a greater art fraud than any copier of Caravaggio. It is not art for grown men to make millions on doodles a child would be ashamed to show to their parents. It is sinful for an art critic today to call all of this “modern art” a sham and to truly “brutally” ridicule its idiotic simplicity and plagiarism. There are no “brutal” art reviews in major newspapers or magazines that ask artists to cancel this culture of pampering horrid art as special expressions of their hidden feelings and descriptive of our fraudulent and criminal modern times. The cover of this book makes this point, but the interior argues the opposite. The cover is a childish doodle in black paint of glasses and a devilish boogy-monster over a classical painting of a bored angel.

The book’s blurb sells modernism as the sad response of an atomic-age-traumatized and thus deranged mind-collective: “postwar artists and writers searched for a new foundation of culture after the massive devastation of World War II, the Holocaust, and the atomic bomb.” So, the response artists had to seeing millions of people slaughtered with extreme brutality, was to allow art to devolve into styles that predate cave-paintings. And current artists are still repeating these scraping-styles because they remain traumatized even if they do not know anybody who suffered in these wars. The blurb exclaims that “modernist art can teach us how to survive a civilization become barbaric”. Really? Can a black square teach anything but the fact that corruption has seeped so far into art deals that even a white blank canvas can be resold by art fraudsters who are helping drug dealers or other crooks to hide their illegal gains in the reputable trade of art resale? Does a black square or a doodle of a fat woman communicate that people shouldn’t kill all of the Jews, or shouldn’t nuke an entire city of Japanese people? I think these lessons would be communicated much better if they came in realistic drawings of these events that make such actions repelling to all who glimpse these sights brought into tragic heights of artistry. Instead, modern art has escaped into nonsense, and non-communication. The silence of simplistic art is an offense against the suffering endured in the events accused of causing this breech in humanities new incapacity to communicate intellectually sophisticating ideas in art. Instead, Foster repeats the other art historians cliché messages that turn into art-heroes the “key figures from the early 1940s to the early 1960s” who are attributed with developing something “new” in their “‘brutal aesthetics’ adequate to the destruction around them.” One of the drawings included in this book is Asger Jorn’s Life (1952): it is a few massive strokes of red, green and black oil paint that depicts a cartoon of a couple of humanoid blobs and a little dragon-like flying blob, with a little orange sun above them. My description oversells the 50 strokes that make up this monstrously over-sold piece of garbage. This piece is just presented without a single word written about it, as the title is never mentioned in the text. The picture that is given more space in the text than others from John is Yellow Eyes. This is just a blob of a humanoid figure curled into a ball with jiggered teeth and giant yellow eyes (122). Foster sells this babbling of a child slapping paint on a canvas for the first time thus: “It is not only the formlessness of such a creature that disturbs the academic genre of the figure; also disruptive is the intensity of its gaze (not to mention the aggression of its mouth). Although this is programmatic in Yellow Eyes (1953), a swirl of acrid colors punctuated by the shrill orbs of the title, it is also active in other pictures of beasts with wild looks that render aesthetic contemplation all but impossible” (119-21). The entire book is written in this style. “Academic” terms such as “genre” are subverted into negatives or have their meaning changed to fit this upside-down world. The lack of “form” in art is the absence of the essential element that art is designed around. If there is no defined and legible form, this is like writing a book without any words in it, or that has a single word or letter stretched into repeating strings, or a set of 40 words that are repeated in clumps. Here is an example: “lakshf hakslhfal alkskkkkkk sssssssssss laaaaaaaaaaaalalalalala”. Imagine if I was instead writing a review right now of a critic who was repeating these types of quotes from a “modernist” novel, and using equivalent language that celebrated this as “formlessness” that is beyond the restrictive “academic genre” and the intensity of the “sssssssssss” in the snake-like “gaze” and “aggression” is “disruptive”. And this critic added that the “sh” hidden in the first “word” was a punctuation of the “shrill orbs of the” Shf “title” of this work. This type of up-marketing of nonsense is deeply offensive to all current artists that spend a career failing to “make it” because they do not know the only path to success is to pay critics like Foster for this type of a glowing review. In this environment Van Goghs cut off their ears and die in obscurity, while their sales-minded relatives make millions on their work over their graves. Meanwhile, the best artists in the market stop drawing and withdraw into office work or other forms of obscurity. The silencing of great potential is the modern “aesthetic” brutality that is being perpetrated on youths who are sold dreams of artistic greatness, but face the reality of the impossibility of success especially when they truly achieve quantifiable artistic heights.

If as the blurb claims, Foster stripped “art down, or to reveal it as already bare, in order to begin again”; then, he would face these flaws and cover artists from these decades who remain in obscurity because these doodelers and anti-philosophers are still being featured as if they are war-heroes coming home from the Trojan War. The blurb asks: “What does Bataille seek in the prehistoric cave paintings of Lascaux?” This is referring to Bataille’s plagiarism of the style of the cave paintings. It is the opposite of innovative to copy cave art and resell it for millions. “Why does Jorn populate his paintings with ‘human animals’?” Perhaps, because Jorn thinks people are stupid animals who are going to buy whatever art historians tell them is good? “And why does Oldenburg remake everyday products from urban scrap?” I would imagine Oldenburg has figured out that he can take garbage and sell it for millions, thus achieving every industrial businessman’s dream. The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC sponsored this book, just as it is purchasing and sponsoring the “artists” featured in this book and in their halls. Babbling about the “project to connect objects and subjects” (231) to confuse readers into imagining the author is talking about something too sophisticating for commoners to grasp is a trick that’s turning 100 years old this year. It’s too old, and it’s time to retire the strategy of selling literal garbage.

My Childhood Dream of Reading Liliuokalani’s Diaries Realized

David W. Forbes, The Diaries of Queen Liliuokalani of Hawaii, 1885-1900 (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, June 23, 2020). Hardcover. 576pp. 98 text illustrations. ISBN: 978-0-9887278-3-0.

*****

I wrote an essay about Queen Liliuokalani of Hawaii in high school. Everything about her life was the pinnacle of the romantic, historical and revolutionary ideals. A female ruler leading her people in the nineteenth century again the forces of colonialism seemed to be a heroic tale that was too neglected in mainstream histories and media portrayals of the Hawaiian Islands. I felt sad that this Queen lost her island in a coup and was imprisoned in her palace residence for the rest of her life. This sadness and sympathy was unique only towards Liliuokalani, as the coups and revolutions against all other monarchs I had read about were portrayed or were perceived by me as positive ends to tyrannical monarchic rule. Obviously, when I saw this curious Queen’s diaries being released from Hawaii Press, I had to request them in an attempt to understand just who she was and what distinguishes her inherited rights to rule a land from those of European monarchs.

The publisher describes the book thus: “Queen Liliuokalani, the eighth monarch of the Hawaiian Islands, is known and honored throughout the world, even though she was never ceremonially crowned. Published here for the first time, the Queen’s diaries, which she penned between 1885 and 1900, reveal her experience as heir apparent and monarch of the Hawaiian Islands during one of the most intense, complicated, and politically charged eras in Hawaiian history.” I would have requested this book through Interlibrary loan back in high school, if it had existed. One of the reasons this story was appealing at the time is because there were few accessible sources to explain who the Queen was, but the few segments of her quoted writing, or her general spirit of defiance was sufficient to elicit interest. Since this is the first release of these diaries, it should be of special interests to all international libraries, and I hope it will become a best-seller. I think I saw a version of the Liliuokalani story turned into a movie, but it was done with a pretty girl that barely spoke, when these entries reveal a highly intelligent and strategic woman with layers that deserve a much stronger portrayal in fiction.

Further, Queen Liliuokalani’s diaries “are the sole—and striking—exception” as the diaries of her predecessors and other high-ranking Hawaiians from that era have not survived. So these entries capture a historic period in this distant region in a manner and from a perspective not repeated elsewhere. The colonizers’ perspective of the islands has been the major source cited in history books, and it really should be cancelled in favor of this native and female description of a land under siege.

“The Liliuokalani diaries for 1887, 1888, 1889 (short version), 1893, and 1894 are a part of the group of documents known as the ‘seized papers’ that are now held by the Hawaii State Archives. These are among the records seized by order of Republic of Hawaii officials in 1895 with the intent of obtaining evidence that she had prior knowledge of the 1895 counterrevolution. The government eventually turned these documents over to the territorial archives in 1921, four years after the death of the Queen. Four of the diaries transcribed here were not seized and remained in the Queen’s possession; today these are in the Bishop Museum. The important 1889 (long version) diary is now in the private collection of a member of her family and its contents appear here in publication for the first time”. This explains that these diary entries have been used as evidence that led to her imprisonment for the last decades of her life. Thus, researchers can finally re-examine this evidence to determine if the claims were warranted, or if her imprisonment was a political strategy to avoid having the people of Hawaii potentially elect their Queen as their democratic ruler, if she was allowed to communicate with the public freely without house-confinement. It seems obvious that counter-spies informed her of this counterrevolution to entrap her and to bar her from power. This type of a maneuver would have been necessary if the Queen was uniquely open to helping her people rise and to protecting their interests over any foreign corrupting influences invading her islands.

The notes and entries describe the Queen’s “private life, thoughts, and deeds during her rule as sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands; the overthrow of her government in 1893; her arrest, imprisonment, trial, and abdication in 1895; and her efforts in Washington, DC, to avert the 1898 annexation of her beloved islands to the United States.”

The cover and overall designs of this book is one of the best I have yet reviewed. The cover image is a simple black-and-white photograph, but it is mystical in its capture of a powerful woman, with a simple cross around her neck, and only a decorative flower and honorary strip to signify her power. She does not appear to be wearing any makeup and her hair are a bit wild despite being held in a loose bun. Her eyes are tearing slightly, but her lips are curling into a slight smile. The title pops off the page in a silverish-gold. The spine is covered in an elegant floral motif. Even the back cover is curiously without text, and instead includes a “Sample of Hawaiian kapa collected on Cook’s Third Voyage”, this being a close-up image of a cloth from a 1787 reproduction. Even the inside-the-cover pages are illustrated with a beautiful water-color painting of the Hawaiian coastline. The front page includes a handwritten reproduction of a page out of the journal from June 17, 1893. The handwriting style shows clarity of mind, determination, and an absence of self-correction or pauses. The Contents are divided into sections chronologically. The “Counterrevolution of 1895” is helpfully labeled, as is the “End of the Hawaiian Monarchy, 1893” chapter, to allow those who are not as familiar with this history to briskly find the sections of special interest to them. The front-matter content explains in detail the “History of the Diaries” and why this content is historically significant. Other practically useful for researchers sections are on “Her Family”, where the members of the royal family are presented in photographs and with brief biographies. Most of these biographical sketches are tragic, and explain why the Queen was uniquely sympathetic towards the plight of the poor. They also explain that the Queen married “the son of Captain John Dominis” who was born in New York, but had moved to Hawaii when he was only six. He became the “Prince Consort”, while the Queen retained power (xxviii).

Across the pages I have browsed through, Liliuokalani’s diary entries consistently offer curious information without wasting space on digressions or rhetorical nonsense. Curiously, her activities are very plain and show that she helped herself without much help in chores from servants. In July of 1886, she describes “cleaning up” her own room. She also describes purchasing items such as “Ice” for “$3.50”. She also writes about “Kahae” borrowing $782 for “baby Nihoa” because the Queen cannot will this baby the land she wants to buy for it (94-5). In 1889, she writes about opposing the construction of a roller-coaster being planned on the island (226). In 1893, she reports that the editor of the San Francisco Examiner has told her that she should respond in his paper to “the other party… saying untrue things about me” (325). Later in the year after the overthrow she describes how Senator Blount has asked the Provisional Government: “‘Has the Queen’s overthrow been done by the U.S. or her people?’” She is being advised by Paul Neumann that her people’s “future welfare” and “their rights” need to “be restored and maintained” (341). Thus, across this year she is being bombarded by American propogandists who are telling her that she should start a counterrevolution to defend her people from foreign occupation. This is blatantly a set up designed to corner her into self-incrimination to legitimize an American overthrow of a government America wanted to annex into itself to rob this island paradise of its natural resources for the benefit of its own businessmen and vacationers. These entries are precisely as-advertised, Liliuokalani reports exactly what she was doing on these historic dates. No equivalent records exist perhaps for any deposed monarch, so this is a very humanizing account on the mysterious concept of inherited power.

It is tempting for me to spend the next few months reading this diary closely and writing research papers about its contents and style, but I am working to physically remove my arm from over this book… I’ve done it! It’s highly addictive, as I must warn you. I am sure that if you spend the money to purchase this book for your private collection, you will return to it on quiet evenings at your leisure. It obviously needs to be in all large and small libraries, but I think this is one of the rare books I also recommend for private home libraries as well. It is sturdy enough that passing it down to your children is a good bet for this book that might become a collector’s item, if this will be the only release of this great Queen’s diaries.

A Painting Without a Concept Is a White Wall

Tony Godfrey, The Story of Contemporary Art (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2020). Hardcover: $39.95. 280pp. ISBN: 978-0-262-04410-3.

****

The term “contemporary” art is likely to be the reason this book is less artistically offensive than collections of “modern” art. By “contemporary” Godfrey means recent, instead of referring to the nonsense or non-art genres of “modern art”. Thus, Tony Godfrey presents recent experiments in rebellious art that frequently is as pointless and anti-artistic as “modern” art, but occasionally hits on experiments that touch on points that have to be made at least once to express the absurdities in our current reality.

The publisher introduces this book as covering a range “from Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes to Marina Abramović’s performance art to today’s biennale circuit and million-dollar auctions… Contemporary art seems totally unlike what came before it, departing from the road map supplied by Raphael, Dürer, Rembrandt, and other European masters… Godfrey, a curator and writer on contemporary art, chronicles important developments in pop art, minimalism, conceptualism, installation art, performance art, and beyond.” Godfrey covers “what art is or should be: object versus sculpture, painting versus conceptual, local versus global, gallery versus wider world.” This summary of seeming opposites explains that while the art covered might be experimental, the descriptions of it that Godfrey presents are mainstream repetitions of standard points raised to justify nonsense art. If we stop and consider why somebody would debate the difference between an “object” and a “sculpture”, we must conclude that he who raises this question is arguing that any piece of garbage, or industrially-produced consumer “object” is just as artistically valuable as a “sculpture” designed and executed by a master craftsman and artist who creates an original masterpiece. If the artistic community thus objectifies art and accepts that it can slide down to zero on the creativity scale and still be worthy of coverage in art history; then, our human culture is going down with it. It is similarly morally and philosophically evil to create an equal duality between a “painting” and the “concept”. A painting without a concept, are a baby or a cap spilling paint over a canvas. The painting of a wall in a house in a solid blue is distinct from a painting worthy of a museum display because the latter has to have a superior “concept”. A critic that asks, “But is it still a painting if it has no concept?” and is willing to accept a “Yes” from the public as affirmative that he should celebrate wall-painting as superior to Raphael is… an idiot. The last two points on this list appear to be two random location opposites that the author added because he felt only two parallel phrases was insufficient, while four was just enough.

The blurb continues, as if picking up on my point regarding if audiences or critics have control over what art is: “He presents multiple voices—not only critics, theorists, curators, and collectors but also artists and audiences.” Nearly all of the quotes across the book are solely from these artists themselves, as they are asked to sell their own work with their standard selling-points. Exceptions are when Godfrey actually quotes from the promotional materials of an art fair: “the idea of contemporary art as a lifestyle choice” (225). Most of the artists are speechless or are struggling to explain what is special about their art or why it’s valuable. For example, Adrian Ghenie says it’s “Weird” that a piece he sold “for a few thousand dollars” is now “coming to auction and selling for millions.” Ghenie is careful to add that the inflation is not his fault, but rather the art world’s (201). Dumas explains her paintings as deliberately designed to “have the same kind of sex appeal as soul music” (125). When Godfrey quotes from a critic this critic is merely called the “one critic”, who said: “is it these art-loving, culturally committed trustees who are waging the war in Vietnam” (49). This sentence ends with a period, and not with a question, so this is a direct attack on art as a violent propagandistic tool. The remainder of the page questions if some artists are making anti-art. And, yes, those who make propaganda art to start a war in Vietnam are indeed also waging a war on the nature of art itself. These perspectives are not useful. The “contemporary” experiments presented in this book need to be discussed by a scientific art historian that can explain how they differ from pervious experiments, and how they echo them. The author of a book on this subject cannot surrender the microphone or the decisions on these pieces to the artists or unnamed critics, but rather has to take responsibility for works being presented in one of the few published art books of the year. If these pieces are selling for millions, it is fraudulent for art historians to fail to object if these prices are falsely inflated through speculation or money-laundering without any merit to them as “art”. If objects are being manipulated for enrichment under the guise of “art”, then these attempts are massacres of the chances of great artists to break through this noise. A critic’s silence or echoing of these fraudsters’ self-perceptions is them acting as assistants in these schemes.

The blurb advertises this book for “upending of the once widespread perception that art is made almost exclusively by white men from North America and Europe.” While some white men in North American and Europe might have perceived “art” as predominantly made by them, everybody else was making “art” and seeing themselves at its center. For example, in 2017, there was a discovery of what is now believed to be the oldest 44,000-years-old cave painting in South Sulawesi, Indonesia of human-animals hunting pigs and buffaloes. from the cave paintings onwards. Other oldest cave paintings are from Australia, India, and southern Africa, but the paintings in western Europe in Spain, France, Russia and Bulgaria have received more publicity and art historians’ attention. It is not radical to point out that some past art historians have been sexist and racist, it would be more radical if this book simply reviewed contemporary art in equal measures from the various world regions covered without focusing on the color of the artists as a relevant element in the quality of the art.

It is amusing to look over some of the projects covered in this book. One of them, Maurizio Cattelan’s Untitled (2018) plagiarizes Michelangelo’s chapel painting, only shrinking it down to a tiny one-room size. The Bodies (III) by the Belgian Michael Borremans appears to be making a radical anti-war statement, as it seems to depict two dead youths in their coats that have been killed in the prime of life; but Borremans explains that the image is a joke that represents two sleeping men as a statement on the “softer” or more feminine side of men while they are asleep on soft pillows (180-2). The image that stands out the most is Tania Bruguera’s El Peso de la Culpa (The Burden of Guilt) (1997-9), which portrays a headless lamp cut open to expose its ribs, and hunt from the shoulders of Tania’s naked body, as Tania is eating what looks like dirt or its meat. While I would have assumed this is a vegan’s anti-meat-consumption crusade, Tania explains that this was what the Cuban rebels did to fight against Spanish invaders to demonstrate their defiance as they ate dirt until they died (136-8). But most of the pieces illustrating this book are more like John Baldessari’s The Pencil Story (1972-3), which shows an old dull pencil and then the same pencil sharpened, with a handwritten paragraph under it that explains that the artist was frustrated and sharpened this old pencil, and “I think that this has something to do with art” (11). While this is a funny way to repeat the “What is art?” rhetorical question this and other “contemporary” art books tend to ask, it still insists that viewers respond to it be agreeing that Baldessari is showing art in his two badly made photographs of a pencil. It is not art. Humanity needs to make a pact to move forward in its evolution instead of devolving into idiotic flattery of those who are just trying. If we are going to reward bad art just because it was made by a human who believes he is making art, then art books need to be thousands of pages long as they include every single person who believes they are deserving of inclusion in art history.

I do not recommend that anybody buys this book. I do recommend that the publisher of this book should find the most negative critic of contemporary art out there and ask this very sour and dissatisfied critic to write their next art history book, and that version will be a book that libraries will need on their shelves because it will kick future artists into seeking the heights of artistic excellence or risk being devoured in this very grumpy critic’s next book…

A Brief Guide on Healing Plants (and on How to Keep Them from Killing Us)

Catherine Whitlock, Botanicum Medicinale: A Modern Herbal of Medicinal Plants (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2020). Hardcover: $29.95. 224pp. ISBN: 978-0-262-04447-9.

*****

As advertised, this is: “A beautifully illustrated, informative, and engaging guide to 100 plants used for medicinal purposes.” Every other page is a detailed biological illustration of a plant from flower to root (though in some the root is excluded, perhaps because it lacks medicinal applications), which is followed by its classification, habits, caution warning, harvesting, and medicinal application. The drawings are elegant and yet detailed. The color designs of the pages are intricate and welcoming. Even the fonts are well-chosen.

“Remedies derived from plants are the world’s oldest medicines. Used extensively in China, India, and many African countries, herbal medicine has become increasingly popular in the West along with other holistic and alternative therapies… Readers will learn… that absinthe, the highly alcoholic, vividly green potable, was traditionally flavored with bitter wormwood (Artemesia absinthium); that cannabis may have been used by Queen Victoria for menstrual pain; and that willow bark contains a chemical similar to aspirin.” The negative “cautionary notes” next to cannabis state that “traditional” cannabis had a 10% THC level, whereas some modern varieties (i.e. skunk) are 67% THC, and this skunk has been shown to lead to “psychosis”. The history section further explains that it had been used by the Chinese and in the Middle East centuries before it made its way to Europe when a Muslim invading sect spread it during their attacks on the Crusaders in the 11-12th centuries. Dr. William Brook O’Shaughnessy introduced cannabis into mainstream British medicine in 1842, and it was from him that Queen Victoria learned to use it (potentially) for menstrual pain (56-7).

The alphabetic order makes it easy to find a specific plant to consider potentially growing or taking it: “from Adonis vernalis (a perennial in the buttercup family) to Vinca minor (also known as the common periwinkle). The 100 plants featured in the book all have a long history of medicinal use or are the subject of new medical research. Many treat a range of conditions, from insomnia to indigestion. Some plants are lovely enough to be in a bridal bouquet; others are considered weeds. Cross-reference features at the end of the book connect specific medical conditions and the plants used to treat them.”

The cross-references in the back-matter are indeed very helpful as they identify one or several plants that help with common ailments, such as fungus, anemia and asthma. The glossary provides brief definitions for those who need a bit of help with the technical terms used throughout. The cover includes marijuana leaves next to a flowering plant, so it can be a funny pro-marijuana statement for somebody to make if they display this book in a home. The descriptions of these plants are given in precise terms that provide the necessary information for an intelligent reader. This is a great approach unlike the ultra-technical or the conversational books I’ve seen on related subjects. The cautionary notes are also chosen to address specific problems that one might not find easily in a brief research before somebody decides to acquire and try a plant. For example, the caution on Cytisus Scoparius is that some hybrids of this plant listed in “horticultural catalogs are… not suitable for medicinal use”. I was recently watching a film about hallucinogenic mushrooms; an American filmmaker travels to Russia and goes into a forest to consume red-hatted and white-dotted mushrooms; as I child, when I learned to pick mushrooms the first major lesson learned was to avoid this mushroom in particular and all other bright-colored mushrooms because they are poisonous and can cause death; and there is a whole group of Russians in this film who are eating this poison and selling it to stupid American filmmakers… Maybe they were eating a variety of more hallucinogenic and less poisonous red mushrooms, but I think they were just poisoning themselves with a doze that brought them to a near-death state, and the users are just happy to still be alive when the vomiting stops. Thus, given humanities tendency to skim over information and try stuff because somebody else said it’s good, the warning labels on a book like this one are essential to avoid major disasters.

Another example of a curious plant with a warning is the Devil’s claw, which is not to be stepped on by mice, or used by those with ulcers (120-1). And the thorn apple can cause hallucinations or coma (94-5). The abundance of caution is such that the general message appears to be that people should eat “tablets or capsules” that have a precise doze of the portion that is meant for consumption vs. growing it in a yard and doing your best to self-medicate (178-9). I would have been more interested in a book that focused on entirely non-lethal or non-harmful plants that I could grow in my home, but those plants would probably be made illegal b modern pharmaceutical companies…

This is a great book for all who are studying plant biology casually, or those who have considered taking “natural” medicines. This book also needs to be in public libraries, so those who are considering some of these cures can briefly check if a given idea is feasible and how to make the most out of an attempted usage.

The History of a Neglected Italian City in the Early Dark Ages (That Were Relatively Bright)

Judith Herrin, Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press, October 27, 2020). Hardcover: $29.95. 576pp. ISBN: 978-0-691-153438.

*****

This is a history of a place and events that took place between 390 and 813 AD. Few documents or art pieces have survived from these centuries, so history books tend to glide over these epochs with general mentions or stereotypes. Thus, historians like Judith Herrin who is brave enough to venture into these historically darkened times are undertaking the essential challenges needed to further the study of history. In contrast, histories that simply rephrase and recycle established European histories from the ages that have been at the forefront of mainstream portrayals of world storytelling are not really adding anything useful to the human discussion of our past.