With: Anna Faktorovich

Mary Jo Putney: Since 1987, Ms. Putney has published over forty books and counting. Her stories are noted for psychological depth and unusual subject matter such as alcoholism, death and dying, and domestic abuse. She has made all of the national bestseller lists including the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and Publishers Weekly. Five of her books have been named among the year’s top five romances by The Library Journal, while three were listed in the Top Ten Romances of the year by Booklist, published by the American Library Association. A ten-time finalist for the Romance Writers of America RITA, she has won RITAs for Dancing on the Wind and The Rake and the Reformer and is on the RWA Honor Roll for bestselling authors. She has also been awarded two Romantic Times Career Achievement Awards, four NJRW Golden Leaf awards, plus the NJRW career achievement award for historical romance. In 2013, she was awarded the Romance Writers of America Nora Roberts Lifetime Achievement Award.

Faktorovich: How did you manage to find a job as an art editor for The New Internationalist magazine all the way in London after you graduated from Syracuse University? Did you find this opportunity right out of college, or a few years later, and if later, what did you do in the interim? It just seems like such a fortunate occurrence to land a major art editor position with a London magazine right out of college. I’m sure everybody wants to know how you did it.

Putney: Actually, I was living in Oxford, England when I got the job. I’d moved to Oxford with a friend. He went to graduate school and I looked for work. I’d had several years of experience working as a designer in California in the years between college and England, so I had some useful skills. The New Internationalist was a magazine about international development and it was just starting up. Working there with a group of brilliant, idealistic young Britons was a terrific experience.

Faktorovich: Have you used many of the experiences, sights, sounds, and the like from the time when you were living in London in your historical novels? Did you visit Scotland while you were in England, or did you read Sir Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson or other Scottish novelists while you were in England that got you interested in the Jacobites, the focus of your Kiss of Fate Ballantine novel?

Putney: We lived in Oxford for over two years, and in that time, we traveled all over the British Isles, from Scotland to Land’s End, and even a journey through Ireland. Those experiences, along with my degree in 18th Century British Literature, certainly inform all my writing. I ‘m interested in lots of things, and I work them into books when I can! As for the Jacobites and A Kiss of Fate—I’ve never felt that Bonnie Prince Charlie was the least bit romantic. Those Stuart ambitions almost destroyed Scotland, so I liked writing a book that expressed that. A Kiss of Fate was the first in my Guardian trilogy, a series of paranormal historical romances that showed what happened behind the scenes to make history turn out the way we know it.

Faktorovich: You say on your website, www.maryjoputney.com, that you majored in English Literature and Industrial Design at Syracuse. How did you first become interested in these two very different roads? You have said in an interview with Claire E. White that Industrial Design was a career plan that was more like to generate a “living” than your dreams and hopes for a career in literature or writing. Did you attempt looking for a job in industrial design after graduation, and did you find a glass ceiling that barred you from entering this path because you were a woman (or you suspect that this was what stood in your way)?

Putney: I became an English major because I loved reading and I had to major in something. In my junior year, I met an industrial design student and became fascinated by what he was studying, so I changed my major. I love design, and good design bears a strong resemblance to a well-plotted—well-designed—novel. Studying design was one of the great passions of my life. I don’t recall ever saying in an interview that design superseded my dreams of a career in literature because I never had any dreams of being a writer! I thought being a writer was the coolest thing imaginable, but I’m a farm girl from dairy country. Becoming a professional author was so far beyond the realm of possibility that it was never even a dream.

As for my design career—no glass ceilings. I like travel and living in different places, and design was a great way to earn a living, so I’d move where I wanted to and then find a job. I never wanted to spend my life working my way up a corporate ladder. If I had, perhaps I would have hit a glass ceiling, but being a top executive was never my dream.

Faktorovich: Why didn’t you stay in London or California to run your own graphic design business? Didn’t these places have more buyers and opportunities in this field? Was rent cheaper in Maryland? If not, what attracted you to Baltimore as a great place to run a business?

Putney: When it seemed like time to return home to the US, I stayed with my brother and his wife in northern Virginia as a base for job hunting. I found work in Maryland and have lived here ever since. That said, I love Maryland’s variety and four seasons and the people as well. Plus—well, I met a guy…. Isn’t that how a lot of lives are shaped? Baltimore shares many challenges with other older industrial cities, but it’s interesting and varied and vital, and much nicer than its public image suggests. (I live in the suburbs, though, not the city. As a farm girl, I like lots of trees around!)

Faktorovich: Wikipedia’s biography makes it seem as if you started your design business in 1980, bought a computer that same year, and immediately sold your first romance, but for some reason it was only published in 1987. Can you explain what kind of work you did with your design business to make a living in those seven years? Would you recommend founding an independent business to women who want to succeed professionally in America? If so, why?

Putney: Don’t believe everything you read in Wikipedia! It’s a great resource for a lot of general things, but what you’re quoting isn’t accurate. I’ve never read my entry. I don’t ego surf, either. Anything anyone needs to know about me is in my books. As for my freelance design work, I did things like logos and brochures and advertising and corporate identity for small companies. I was never going to get rich, but I really liked being self-employed. It’s a matter of temperament, I think. Some people like the variety and social connections of working in a sizable company, and some of us like being independent and are willing to accept income insecurity.

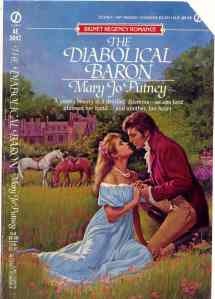

The Wikipedia entry is wrong on the timing about my writing, too. I bought my first computer and printer on December 31st, 1985 so I could get the tax deduction. I started my first book, The Diabolical Baron, in March 1986, and was offered a three book contract in early July. That first book wasn’t published until 1987 because it sold on a partial manuscript and I didn’t finish it until November 1986. A year is pretty standard to get a book from submission to publication.

Faktorovich: How did you manage to sell your first Regency romance to Signet in a week, and also get them to offer a three-book contract on top of this? In a 2004 interview with you for the Internet Writing Journal, Claire E. White explained it thus: “A friend of a friend got her the name of an agent, who gave her some editorial advice then sent the revised manuscript off to Hilary Ross, the Regency editor at Signet/” You later add that this friend was a “well-established author,” who connected you to her “former agent.” I have seen this wording many times, but what does it really mean? Can you be the “friend of a friend” and give me the name of your agent, and would your agent consider my submission seriously? Who was the friend that made this contact for you? Do you think it was easier to sell a first-time author to a major romance publisher in 1987 versus today? In your 2014 novel, Not Quite a Wife, you thanked your new agent, Robin Rue, was this a difficult transition; why did you switch and how?

Putney: These are all questions that could run very long! The “friend of a friend” is a generous author who has written many books as Lindsay McKenna. She offered the name of either her old agent, who was fast, or her new agent, who was slow. I said, “Give me the name of the fast one,” because I’m impatient and I wanted professional feedback. I didn’t really expect to be taken on by her. It’s kind when someone gives you the name of an appropriate agent, but really, that’s as far as a referral goes. The agent will accept or reject you based entirely on what she thinks of your work.

The agent in this case was Ruth Cohen, now retired, but my wonderful agent for nineteen years. She made some editorial suggestions—basically to tighten the prose in some places, and clarify the characters emotions—then sent my edited 119 pages to Signet Regency editor Hilary Ross with a little note saying Hilary might be interested. Hilary was also a very fast responder (do you see a theme here?), she liked what she read, she asked to talk to me in person, decided I sounded like a Real Writer, and called Ruth and offered a three book contract. There wasn’t a lot of money in traditional Regencies so she wasn’t risking a lot financially, but she liked my potential, so she took a chance on me.

I’m still rather stunned by that! Hilary was the only editor Ruth sent the manuscript to. Ruth thought that we’d be a good fit, and she was right. The romance genre was expanding then and hungry for new voices, so yes, it was much easier to sell to a traditional publisher then than now. I was very sorry when Ruth retired—we still keep in touch—but by that time, I was pretty well established. I talked to a couple of different agents. Robin Rue of Writers House represents one of my best friends, who thinks highly of her, I talked to Robin and we clicked, and I’ve had no regrets. As transitions go, it was relatively painless.

But giving an aspiring writer the name of one’s agent doesn’t guarantee anything except that a submission will almost probably be looked at. My recommendation would mean nothing more because agent and editors make their decision entirely on what they read.

Faktorovich: In my research for a book on gender bias in romance and mystery publishing, I found that most female romance novelists were married, while most female mystery novelists were divorced or otherwise had many negative relationships in their past. Why did you avoid marriage, and what are your thoughts about this institution? You have mentioned that you have an “S.O.,” or significant other, can you describe him or her and your relationship? Perhaps, you can give a back-cover blurb for a hypothetical novel based on your longest real-life relationship?

Putney: “He [DH or the Mayhem consultant] was a great guy with a really sharp brain, a sense of humor that wouldn’t quit, and he liked intelligent women and travel. She was an independent woman with no maternal urges and an introvert’s need for lots of peace and quiet. They were both deeply involved with their careers so they hung out a lot [for 30 years], but felt no great need to wed. Until one day it seemed like the right time to marry, so they did.” That was three years ago, and we still get along just fine.

Faktorovich: Have you ever attempted writing an “honest” romance novel about your realistic relationships with men? If not, why not? Do you read any romance novels by other novelists, and if so, do you escape into these idealized fantasies, or read them with a critical eye?

Putney: My novels are emotionally honest and sometimes include real incidents, but they’re written for entertainment, they’re not documentaries. I do read other romances as long as the writing is good, I like the story and characters, and the heart of the story feels true to me. But the critical eye is always there, of course.

Faktorovich: You sent a proof of a forthcoming novel to me, Not Always a Saint. How far in advance of publication do you receive proofs of your books, and do they always look so similar to the final released versions? Do you do any editing after you receive printed proof copies? Or are these printed for the reviewing media? Are reviews the only thing that’s added or changed to the cover or interior after the printing of a proof?

Putney: The ARC—advanced reading copy—that I sent you arrived about—five or six months before mass market publication, I think. A number of them are printed up for reviewers and other interested parties. I usually get a medium sized box and often use them as contest prizes.

The content is the same as the page proofs that have been sent to me, but at this point any changes are minor tweaks to catch errors. Any rewriting would have been done earlier, at the copy edit stage. The corrected proofs are what go into the final version. Often ARCs have plain paper covers. Using the actual cover costs more and is only done for lead authors, and it’s part of the book’s promotion since the real cover is more enticing than a plain blue wrapper.

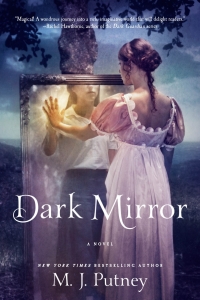

Faktorovich: Have you ever had an urge to write a book about fashion design or another non-fiction topic? If you get this urge, would you write it under a different name? Why did you use the initials M. J. Putney for your fantasy novels, instead of just going with a completely different name? Do most genre novelists take on other names to keep the brand like “Mary Jo Putney” purely associated with a single genre, or a single section in a bookstore? Do you wish this wasn’t the case, or do you see benefits in this system?

Putney: No, I can’t say that I’ve ever felt inclined to write about a non-fiction topic. A lovely thing about fiction is that it’s possible to incorporate just about anything that interests me. I once saw a book about historic mechanical toys, and they became a major thread in a novel. Using initials was to signify that the book was by me, but a different genre so potential buyers would know what they are getting. Not all historical romance readers like fantasy, for example. I have no problem with this. The aim is clarity. I don’t want anyone to buy a book and be disappointed because it’s different than expected.

Faktorovich: On your website, you mention that you released your “first independently produced audiobook, Thunder and Roses” in October, 2013. What was it like releasing an audiobook independently versus working with a major publisher? Why did you decide to venture out independently? Did it have to do with your earlier entrepreneurial spirit, or was it anything like founding a new mini business venture? What are the benefits and drawbacks of releasing a book or an audio book independently today? Would you recommend it for other authors, either those starting out or for other best-sellers?

Putney: Traditionally, audio rights are sold by the publisher to a specialist audio house and authors aren’t involved at all. Then Audible and ACS, both subsidiaries of Amazon, provided tools for authors to produce their own audiobooks. I am ever curious and I’d also heard that while doing audio is expensive, the pay off is very good, so I decided to try. It was interesting, but the royalty basis changed and doing my own audiobooks was no longer profitable, so I stopped after three.

The issue of publishing independently is vast and widely discussed on line. Briefly, there are advantages to traditional publishing, and to going indie. I’m fortunate enough to write for a publisher I really like and which treats me well, but I’ve independently published almost all of my backlist (older books to which I’ve reverted rights. About twenty books and novellas and a few more to come.) Doing both traditional and independent publishing is now considered “hybrid,” and many authors find that the combination suits them on a project by project basis. It’s a very individual choice.

Faktorovich: What about the independent world-rights ebook version of your Dark Mirror YA trilogy? How did this experiment go? Was it profitable (did you make more money than you spent on the designs and other components)? Was it more profitable than ebooks you’ve done with major publishers, if you’ve done any of these?

Putney: It wasn’t at all profitable because it’s much more complicated to promote books in foreign markets, and in many countries e-books and e-readers haven’t really caught on yet. But it’s a good series that I love, so I’m not sorry I did it. Eventually I’m sure the books will at least break even.

I was one of the early people to put my backlist titles out as e-books, and for the first year or two I made a lot of money without much effort. The golden age passed quickly and indie earnings have diminished as many more books flooded into the e-market. But I have an established name, so with some promotion on my part, I still do pretty well. The last couple of years, my income has been roughly equal between indie e-books and my traditional publisher. (My traditionally published books have all had e-editions for years.)

Faktorovich: You include a note on the front page of your website with an apology for the deletion of page 362 from your novel, No Longer a Gentleman (2012), by the printer, and include a link to the electronic version of this page. How many readers wrote in with complaints about this before you posted this note? Do you still receive some complaints even after you posted this apology? Out of your 77 Amazon customer reviews (with a 4.5-star+ average), the two with single-stars do not mention this error. How many books had this glitch in them? Are there steps authors can take to prevent printer or publisher errors?

Putney: A sizable chunk of the initial print run had the page missing, though I don’t know the percentage. I heard about it from a reader within hours of the book’s release. My publisher immediately pulled as many of the flawed books as possible and made the printers do a replacement print run as soon as they could. It did hurt the book’s print sales, though. To this day, I occasionally hear from people who’ve found a copy with that page missing. Readers have been very nice about it, luckily. Besides having the missing page on my website, Kensington also replaced flawed copies if they were notified.

There really is nothing that an author can do to prevent such production problems. Sometimes mistakes happen. For one of my contemporaries, a whole chunk of many pages was missing and there was a piece of an Olivia Goldsmith book that had been run on the presses just before my book was printed. No one wants this to happen, and my publisher did its best to compensate. An author needs to shrug and move on.

Faktorovich: In the interview with White, you said that you like writing because you don’t have to “wear pantyhose” and gave the following summary of what your average writing day is like, “I’m most creative in the evenings, so in the morning I start slowly, read the paper, run errands, go to Curves, and read email. When I’m on the computer, I always have music playing from CDs, and it’s always flowing and without vocals because words distract me too much. In the afternoons, I might do research and editing, and new text is most likely to be generated between 7:00 and 11:30 pm. It can take all day to settle down enough to actually write.” Has your work schedule changed significantly over the last decade, and if so how? Do you stop for weekends? Where do you get the books or newspapers for your research: bookstores, libraries, online, electronic texts? What are some of the writing habits that have helped you to successfully and consistently publish fiction?

Putney: My writing habits haven’t changed to any noticeable degree. I’m not particularly disciplined, but I am driven and the closer a deadline draws, the faster and more panic-stricken my writing becomes. To be honest, it amazes me that I ever finish anything, but so far, so good!

I have a ton of research books, but Google is also a great tool, especially for small things I need to learn about quickly, like the name of the gorge in the Douro River that blocked development of vineyards on the upper river until the 1790s. I still prefer print books for in depth research though—I currently have two stacks of books about a foot tall each on Spain, Portugal, and the Peninsular Wars.

Faktorovich: One of the most prolific novelists in the history of publishing, Dame Barbara Cartland, published 722 romances across her life. You are currently pushing past 60 novels. What do you think pushed Cartland to write a novel in a month, instead of writing it over a period of around 10 months that you say you need to complete one of your novels? Is there a pressure from your publishers for you to write new novels faster, or are there limits to how many novels they can release by a single author per year that limit how many novels you could publish per year, if you were to become suddenly more prolific? Is most of your time spent on editing and perfecting a novel, as opposed to just writing down a first rough draft?

Putney: Barbara Cartland was a natural storyteller with a talent for light, entertaining romances. In later years, she dictated her books to secretaries, I believe. I write a different kind of book with more psychological and research depth. I’m probably also lazier than she was. My publishers have always been very good at working with my natural writing schedule. I don’t write first drafts—a single draft is it. I edit and fuss all along, so by the time the book is finished, it’s in pretty good shape. And I’m always pushing the deadline so there’s no time to set it aside. I’m not necessarily recommending this approach, but I think we’re hard wired for a particular process, and this is the one I’m stuck with.

Faktorovich: You begin your forthcoming Regency romance, Not Always a Saint, with a description of a newlywed battered woman being treated at an infirmary, and tossing her wedding ring to the floor, offering it to help fund the infirmary, as she plans to leave her husband to stay with a friend. The book that precedes it in The Lost Lords series, Not Quiet a Wife, begins when estranged married partners reunite accidentally, after a decade apart, and they spend most of the novel trying to make their marriage work again. You are known for writing somewhat anti-formulaic romances that discuss abuse, alcoholism and other problems couples face while trying to make a relationship work. If romances are escapist fantasies about idealized relationships that women enjoy reading because they help them to escape from the real-world problems in their own relationships; why do you think your novels have found such a wide readership and acclaim from awards committees? Do you think it’s important to insert realistic problems into romances to help women deal with the problems they are facing in reality? Can you explain why these types of scenes and situations appear frequently in your romances?

Putney: Readers are as diverse as writers, and fortunately, there are a good number of them who like my darker, more realistic stories. A good thing about genre romance is that the happy ending is guaranteed, so it’s a safe space to explore topics that can be painful such as domestic abuse and alcoholism. Such stories interest me, so that’s what I write. Other authors and readers have no interest in more realistic stories, and that’s just fine.

Faktorovich: On the first page of Chapter 1 of Not Always a Saint, you write, “No matter how unquiet his own mind, his medical skills helped heal ailing bodies, and the occasional sermons he gave in the chapel he sponsored sometimes helped heal wounded souls” (9). How important is it to create likable characters that are doing good in a brutal world to keep an audience’s attention? Laurel Herbert is helping heal the sick by her brother’s side in the chapter before this quote. She is the central character in Not Quite a Wife, where at the start of the story she is also helping in the infirmary, this time to heal her estranged husband, Lord James Kirkland. Have you ever attempted creating a mean-spirited and cold female character that is brutal towards her partner, but who loves her anyway? If you try creating an unlikable female or male hero, do you frequently hear from fans with objections?

Putney: Mean spirited characters don’t appeal to me at all. People make mistakes and much can be forgiven if there is remorse and a desire for redemption, but meanness is just mean. My characters are just about all warm, compassionate people who may have scars and hang-ups from the past. They make mistakes, but they are never mean. I have to spend months with them, after all, so I need to like them!

Faktorovich: Not Quite a Wife ends with news of an unexpected pregnancy after a miscarriage and Not Always a Saint ends with a marriage and the promise of unsaintly lovemaking. Why do you think a relationship goal being achieved is an important part of romance novels’ endings? What would your agent or publisher say if you left a romance in the middle of uncertainty or in the middle of just an average day for a couple, without bringing the relationship to a climax and a resolution with a major change in the relationship (especially if you’re nearing the end of a series)?

Putney: What you’re suggesting wouldn’t work well as a book. Just as in a mystery, it has to be established “who done it” and epic fantasy is the struggle between good and evil and the good guys need to win, a romance is the story of the courtship, the developing relationships that ends in a lasting commitment that readers can believe in. Once they’ve made that commitment, the emotional tension ends. It’s not uncommon to have a brief epilogue in which the couple can be seen enjoying life with each other after the sturm und drang of the main plot. But the real story arc ends with the commitment.

Faktorovich: Do you have to consciously simplify your language, delete passive voice, and make your sentences choppier and more direct, or is this something that comes naturally to you? It seems as if novelists with shorter sentences, average word length, and average paragraph lengths are selling more books, and that these averages are getting lower with the decades. Is there any pressure from your publishers to make the books more “readable,” and if so, how so? How have your publishers’ preferences regarding these elements changed with the passing decades? Your sentences seem to be a bit more complex than the current standard. For example, “‘I managed to get quite a bit of Jesuit’s bark tea down him and that stopped the fever before the attack was full blown…’” (Not Quite a Wife 53). Are you likely to receive a comment from your editor on this proof copy asking, for example, for you to shorten this sentence, by let’s say, eliminating “was full blown” and replacing it with “worsened”?

Putney: I’ve had four major publishers over the course of my almost thirty years of writing, and none of them have asked me to change my prose except to correct error. I have a degree in 18th Century British Literature and my writing sensibility was powerfully shaped by Georgette Heyer, so long, complex sentences come naturally to me. They were perfect for the traditional Regency romances I started with since such books are language mad, but as I moved into historical romance, I realized that I needed to develop a more streamlined, accessible style. But as you noted, I still have a tendency to write the longer, more complicated sentences. I presume that people who don’t like my style don’t read my books, and that’s fine.

Faktorovich: What advice do you have for writers who are dreaming about making novel writing into their career, but are facing extraordinary billion-to-one odds? What should or can they do to increase their odds of success on this steep climb?

Putney: Read much. Write much. Try. Fail. Try again. Fail better. Talent is common—it’s tenacity that builds a writing career.

I’ve loved Mary Jo Putney ever since I discovered her. I was a nursing student at the University of.MD, Baltimore at the time & juggling my studies with raising 3 kids & a frequently absent but brilliant husband. My mother lived in Taiwan (missionary) & my mother-in-law in Saskatchewan so no help from family. My stress reliever was romance novels of which I found Mary Jo Putney to be the best. TangentialIy, I also liked to visit a thrift shop run by a charming proprietor who scolded me like a Jewish grandmother. OMG, did that ever feel good!

This interview was outstanding! Faktorivich asked the questions that illuminate the personality behind beloved characters brought to life by Ms. Putney. I read it with intense interest & was sad when it ended. I wanted these two voices to continue their conversation so I could sit at their feet. Such knowledge & compassion for people! I am in awe.

LikeLike