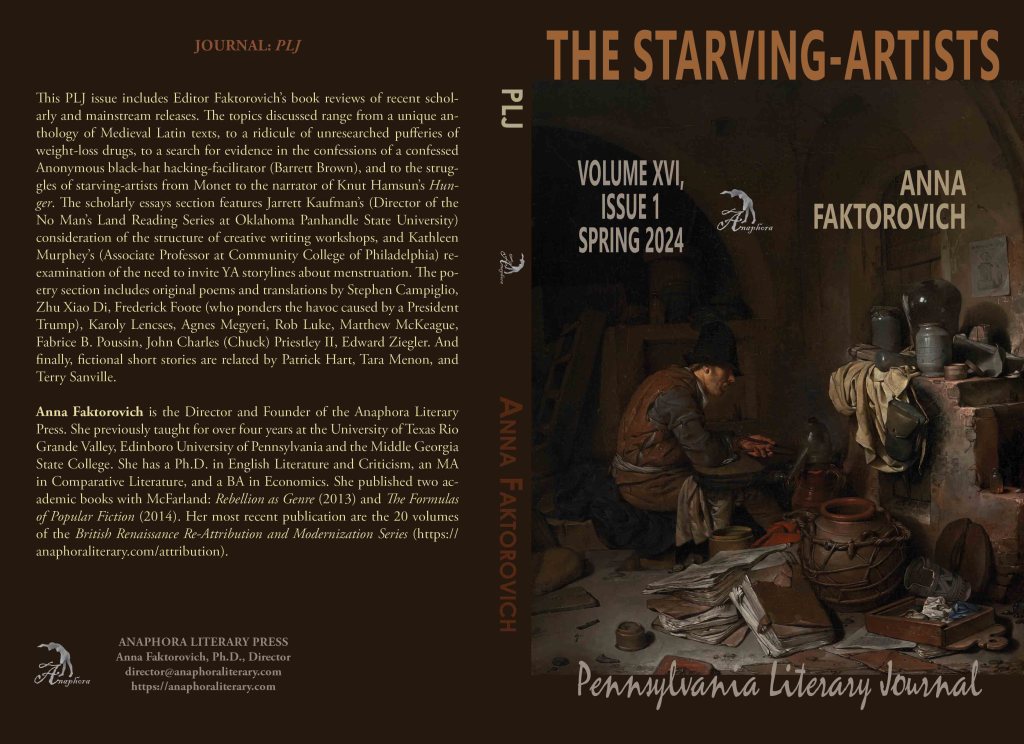

Anna Faktorovich

British Medieval Latin Texts: Thoroughly Translated and Introduced

Carolinne White, and Catherine Conybeare, The Cambridge Anthology of British Medieval Latin, Volume 2: 1066-1500 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, January 2024). Hardcover. 522pp. Index, bibliography, maps. ISBN: 978-1-316-63729-6.

*****

“A series of Latin texts (with English translation) produced in Britain during the period AD 450-1500. Excerpts are taken from Bede and other historians, from the letters of women written from their monasteries, from famous documents such as Domesday Book and Magna Carta, and from accounts and legal documents, all revealing the lives of individuals at home and on their travels across Britain and beyond. It offers an insight into Latin writings on many subjects, showing the important role of Latin in the multilingual society of medieval Britain, in which Latin was the primary language of written communication and record and also developed, particularly after the Norman Conquest, through mutual influence with English and French. The thorough introductions to each volume provide a broad overview of the linguistic and cultural background, while the individual texts are placed in their social, historical and linguistic context.”

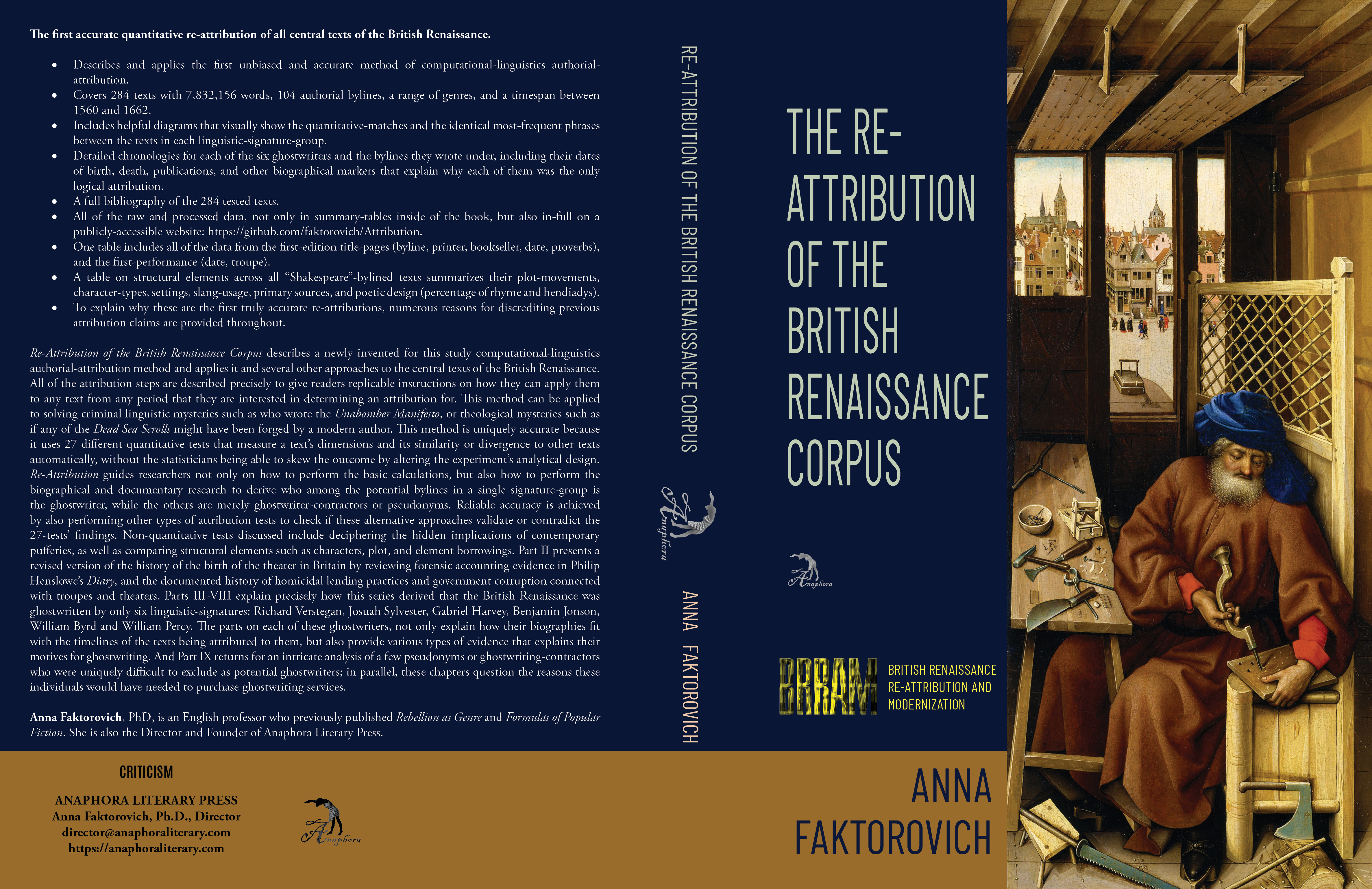

In my British Renaissance Re-Attribution and Modernization (BRRAM) series’ Richard Verstegan’s Restitution for Decayed Intelligence in Antiquities volume, I explained that the history of Britain, as it is currently taught in schools, was fabricated by Britain’s ghostwriting Workshops. Verstegan, in particular, was instrumental in forging many Old and Middle English texts that he created by translating Latin texts into these variants of Old German and selling these as expensive antiques to collectors, and in transcription to book-buyers. Restitution was the first Old-Middle English dictionary in part because Verstegan had spent the previous decades fabricating these linguistic variants. Restitution also explains that modern geneticists have concluded that modern Brits migrated to Britain from German-Dutch regions in around 900 AD, and then serfdom was introduced over these migrants after the Norman conquest around two hundred years later. Latin had been the official language of Europe, and the regional variants, such as Old German were merely erroneous usages of Latin that had diverged into distinct languages. Thus, the study of Latin manuscripts from 1066-1500 is the study of almost all pre-Renaissance-Workshop and pre-English authentic texts created in Britain (though some of these Latin manuscripts might have been created in Europe, and merely later claimed to have been British in origin). Before the Norman enslavement of the British population, they had no need for legal contracts designed to enforce this enslavement with rules fabricated by the enslavers.

The “Introduction” to this book explains that most of these documents were stored “for centuries” at only two central locations, “Westminster and in the Tower of London”. Their publication in this book is a major step in a disclosing direction, as their had been intentionally off-limits to the public for most of British history because this allowed them to be manipulated by having new forgeries introduced when history needed to be altered, such as creating a foundation for a new peerage, or a new aristocratic claim to an enormous piece of land. A forger merely had to labor at one of these locations as a ghost-clerk to introduce volumes of documents that were unreadable to nearly all in the mostly illiterate public. The “Introduction” to this book reports similar unsubstantiated propagandistic books as most books that are designed to puff the intellectual superiority of Brits in early British history. “By the twelfth century, access to education was increasing at all levels and a more secular syllabus was also available” (6). The author cites another modern critic as a source for this claim. There are no statistics for the literacy level in Britain in the 12th century, and if the surviving documents are counted as the only texts that anybody wrote in that century, there was only a handful of Latin scribes who continued studying the Bible to enforce the feudal system on the masses through the power of the God-sponsored monarch. At most there were 5% of American slaves in the 18th century who were minimally literate or had a basic ability to read and write. Then, why would the British enslaved population under feudalism in the 12th century have had any access to an education outside of the indoctrination necessary to force their labor? The author does not address such questions, and instead digresses into generalities such as the “characteristic elegance” of Aelred’s writing style, adding that the “handwriting is often extremely beautiful” (8). There are no references to “carbon-dating” or even few references to dating any document by means other than accepting the stated date as true. One of the only estimated datings appears on “Tex II.1b” on “The Battle of Hastings” that is described as “dated no later than 1125”, seemingly merely because the Latin spelling variants in the text match other texts credited as created at around this century. The subtitle of this book is the precise “1066-1500” time-period, so the author should have invested a bit more research into explaining why the stated dates should be believed, or why undated texts have been dated as they have been. The positive element that is explained at the end of this “Introduction” is that the point of this volume is to give access to the public to read the contents of texts that have been inaccessible until now. Interesting details include “the Abbot of St Albans’ epic-style description of his sea crossing in 1423”, or “satire and black humor, for example in the chronicle of Meaux Abbey in Yorkshire, whose author comments… that after the naval battle of Sluys in 1340, the fish had eaten so many dead Frenchmen that if God had given fish the ability to talk, they would have spoken French” (29). While humorous, this reference is also likely to point to a propagandistic exaggeration, as there were clearly far fewer ships or soldiers used in battles during this period, starting with the Norman Conquest, which appears to have in fact been achieved with near-no resistance. But a tale of documentary conquest by writing contracts in a language the native Brits did not understand would not have been as inspiring for nationalistic pride.

The Norman Conquest is covered in the first translated piece in “Section II.1”: “The Bayeux Tapestry”, dated: “?before 1080”. The prefacing remarks on it explain: “Although it has been preserved for many centuries in Bayeux in Normandy, it is likely to have been made in England, as English needlework was renowned already at this time”, having been puffed in other sources that could have been Norman propaganda, such as “William of Poitiers’” Gesta Guillelmi (33-5). If English women learned the French style of needlework, their output would have been indistinguishable from the French or Norman, and thus this is a cyclical argument that does not provide any evidentiary reason to believe that this tapestry was made outside the place where it was stored: Normandy. This is a great example of the problem I mentioned where many Latin “British” documents tend to have content and provenance that suggests they are more likely to have been created in continental Europe as propaganda aimed to minimize Britain and to glorify conquests over Britain.

The faults with this publication I have mentioned are not unique to this particular author, but rather are to be found in all books that cover this period of British textual output. If I was still researching the Renaissance for my BRRAM series, I would have read most of this book cover-to-cover, as most of the Latin texts and translations provided in this volume have not been previously accessible in any digitized format. And the sections on the history, and linguistics that introduce each of these pieces should make it extremely easy for new and established researchers in this field to briskly enter each new subject with their help, so they can focus on the evidence in these manuscripts that is relevant to their unique research projects. Spotting linguistic or historical errors in the past interpretations of these manuscripts cannot begin without such reference materials that compress this potentially erroneous information. The inclusion of both original Latin, and English translations is also rare, as typically only one of these is included in anthologies. One down-side is that there is only a single illustration or a copy of one of these manuscripts: “Example from 1296 of the Feet of Fines Document”. Copies of at least a page out of all manuscripts in this volume should have been included to allow the public to judge if the same handwriting style appears in manuscripts that are supposed to be from different centuries, allowing for the identification of backdated forgeries. The author probably did not have the budget to pay these archives thousands or perhaps millions of dollars to digitize these pieces and for permission to reproduce them in a scholarly book intended for commercial use. Some archives do not allow for self-photographing of such manuscripts. Because modern aristocrats still hold lands that rely on some of these documents, they really should have been digitized online as soon as this became technically possible.

Despite my many objections, I am delighted to have this book in my digital collection, so that I can use it if I ever come across the need to check Latin sources from this period in my research. I thus recommend it to others who occasionally or regularly have need to check such historic sources, including private home libraries, and major university libraries.

Critical Guesses and Digressions on Old Norse-Icelandic Undated Manuscripts

Heather O’Donoghue, and Eleanor Parker, eds., The Cambridge History of Old Norse-Icelandic Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024). Hardcover. 634pp. Index. ISBN: 978-1-108-48681-1.

***

“A landmark new history of Old Norse-Icelandic literature…, a… guide to a… body of medieval writing… The latest in-depth analysis of every significant genre and group of texts in the corpus, including sagas and skaldic verse, romances and saints’ lives, myths and histories, laws and learned literature… Innovatively organized by the chronology and geography of the texts’ settings—which stretch from mythic history to medieval Iceland, from Vinland to Byzantium—they reveal the interconnectedness of diverse genres encompassing verse and prose, translations and original works, Christian and pre-Christian literature, fiction and non-fiction.”

My BRRAM research in Verstegan’s Restitution indicated that Verstegan forged or fabricated a fictional mythology for Germanic people across Europe. Verstegan took brief propagandistic earlier references to satanic or semi-Roman deities in texts written by Catholic priests and added fiction to expand these into what seemed like a structured mythological narrative. As I searched for pre-Renaissance manuscripts that substantiated this narrative, I learned that Old Norse-Icelandic literature offered the richest cited examples, but these sources tend to be difficult to access either in digitized originals or as transcriptions or in translation. Thus, this book was a necessary request-item for review. As its “Introduction” reports, “With the conversion to Christianity in 1000 CE came literacy”, and pre-Christian texts were thus mostly written by Christian propogandists that were motivated with making the past look worse than the present feudal system that not only enforced labor but also claimed belief in the Christian mythology or fictional deity. Christian scribes could write fiction that they could present as authentic Norse mythology carried by “oral” tradition. This “Introduction” acknowledges that this mythology seems to echo “the rise of the European novel” (1), but the likelihood that these stories could have been forged in parallel with the earliest European novels is not mentioned.

The “Manuscripts and Textual Culture” section of the book explains the broad rules that were used to set dates on anonymous and undated manuscripts; for example, “The oldest script-type found in Icelandic manuscripts is Caroline minuscule, which was common up until the first decades in the thirteenth century” (41). This can mean that there was a single scribe who wrote this cluster of texts that have been instead spread as dated across centuries. This is a common mistake in such antiques, as most archivists fail to acknowledge that when texts they want to be from different periods seem to be written in a shared handwriting style this means they are by a single scribe in a single period.

The paragraphs in this section tend to include general statements in the body of the paragraphs, with extensive citations of past scholarship on each point in the citations. This scholarly style means that most of the text is a puffery of past scholarship, without in fact doing any in-depth explaining of the subject at-hand. For example, there is a claim that the “oldest extant Icelandic paper manuscript” is “from 1539-48” from the “notebook that belonged to Gissur Einarsson, bishop of Skalholt.” The note on this claim describes the path “used for purchasing paper by the sixteenth-century bishop”, and dating “paper manuscripts based on watermarks”. In most studies I have read the term “watermark” refers to a date imprinted into a paper watermark; such dates could be watermarked in at significantly later years, decades, or centuries than the claimed watermarked date. Thus, this section should have mentioned if this analysis is merely based on such a written date, or some carbon or otherwise dating of water-markings or anything else that in fact requires scientific analysis. Instead, most of the body of this paragraph is full of hot-air that does not actually explain why the “1539-48” date is to be believed. For example, if the watermark had a specific year in it, then this should have been a specific year, such as “1539”, and not a year-range that suggests some kind of analysis; but carbon-dating and other such analysis cannot narrow the years down to a single decade (46).

The main problem with this book is that it does not include any full transcriptions or translations of the literature that is being discussed. For example, the chapter on “Heroic Poetry” includes pages of criticism before the first couple of stanzas are quoted. While the introduction mentioned that there are some digital archives that hold some of these manuscripts, most of them are still inaccessible, and thus discussing them critically without providing full transcriptions does not help readers with being able to critically evaluate and benefit, since the conclusions reached by these literary scholars can be entirely erroneous or different from what another reader might gather from these texts. Quoting from the middle of texts is not likely to be beneficial without the rest of the narrative, with a historical and linguistic introduction to the piece. Here is one such fragment from Hervarar saga ok Heidreks, or “The Battle of the Goths and Huns”: “That is acceptable for a bondmaid’s child, the child of a bondmaid though it may be fathered by a king. The bastard sat on the mound when the prince divided the inheritance” (171). The previous short paragraph briefly summarizes that a character has refused to “share… the ancestral magic sword”, so a higher price was offered, followed by this insult. This passage hints that this was propaganda written against local rulers’ claims, and in favor of European monarchs who were attempting to gain control over this region by making these rulers appear corrupt, and as if they had a bastardly origin. A few paragraphs earlier, the author of this chapter explained that Hervarar is “one of the earliest-composed legendary sagas, although these particular verses only survive in some late Icelandic manuscripts” (170). The author is not concerned enough to offer supporting evidence for this dating. If only “late Icelandic manuscripts” survive; then, this piece cannot be dated as the “earliest” manuscript. Its content is a blatant propagandistic narrative that was relevant to the “late” period, even if the warring sides changed. The surrounding notes do not explain where this entire poem can be accessed in the original or in translation. If this critic’s interpretation of the dating and contents is entirely incorrect, a researcher reading this section would have to travel to this archive themselves (potentially) to perform their own research, just to disprove the poorly researched assertions made here, and repeated in earlier studies. There also do not appear to be any illustrations in this lengthy book of the manuscripts under discussion.

While searching for specific texts might help some researchers, most will be very frustrated as they attempt to read this book. Thus, I do not recommend reading this project unless somebody is a specialist in this field and knows what they are looking for.

A Horrific Personal Anecdote About Insulin-Equivalent-Poison as a Weight-Loss-Tool

Johann Hari, Magic Pill: The Extraordinary Benefits and Disturbing Risks of the New Weight-Loss Drugs (New York: Crown Publishing, May 7, 2024).

***

“A… look at the new drugs transforming weight loss as we know it—from his personal experience on Ozempic to our ability to heal our society’s dysfunctional relationship with food, weight, and our bodies. In January 2023, Johann Hari started to inject himself once a week with Ozempic, one of the new drugs that produces significant weight loss. He wasn’t alone—some predictions suggest that in a few years, a quarter of the U.S. population will be taking these drugs. While around 80 percent of diets fail, someone taking one of the new drugs will lose up to a quarter of their body weight in six months. To the drugs’ defenders, here is a moment of liberation from a condition that massively increases your chances of diabetes, cancer, and an early death. Still, Hari was wildly conflicted. Can these drugs really be as good as they sound? Are they a magic solution—or a magic trick? Finding the answer to this high-stakes question led him on a journey from Iceland to Minneapolis to Tokyo, and to interview the leading experts in the world on these questions. He found that along with the drug’s massive benefits come twelve significant potential risks… What do they reveal about the nature of obesity itself? What psychological issues begin to emerge when our eating patterns are suddenly disrupted?”

Around 7 years ago, I did a full spectrum of lab tests that determined that I was close to becoming pre-diabetic. I had gone to a digestion specialist because I was concerned that I might have still been suffering from side effects of h-pylori food poisoning that had given me an ulcer a few years earlier. Instead of addressing this concern, that stomach-doctor was lobbying me to get a colonoscopy and to perhaps to a weight-loss surgery. I had gained around 100 pounds across the previous few years after another doctor had put me on a steroid-spray drug for my light sinus problems. The doctor who ordered lab-tests refused to see me again when I refused to do the invasive procedures he recommended, so I had to research the lab-data myself by searching for what each of the tests (hundreds of data points) was stating about my health. When I researched my weight (248 pounds at the peak in 2016), I realized for the first time that I was classified as morbidly-obese. Back in 2009, when I started my PhD studies, I was at my lowest weight in a while at around 148 pounds. I had not weighed myself outside a doctor’s office almost ever, being entirely unconcerned regarding my weight (except for moments such as when I was seriously considered for an acting role in 2008 at my lowest weight, without having looked in the mirror to check my looks had improved). When I researched obesity in 2016, the answer I found was going vegan, and so I moved rather rapidly in that direction, and lost around 100 pounds, dropping back down to around 148 temporarily by the end of 2017, before climbing upwards to 160-70 and staying at that weight through the present. I have changed my diet occasionally. Eating almost no processed food led to the low-point, as did precise calorie-counting with an app and keeping the calorie-count low to decrease the weight. Aside for my solid will-power, eating large quantities of unprocessed fruits and vegetables through the bulk of the loss kept me from being hungry simply because of the chewing labor involved and the fullness felt after eating such buckets of good food. I have also been hydrating with water and tea regularly, whereas before I almost never drank simple water just to meet a hydration-minimum, if at all. And I have been exercising daily for over an hour with aerobic, weight-training and stretching sets, across these years. I have occasionally eaten non-vegan foods whenever I have traveled to conferences and the like across my diet years, as practically always wins over the rules of this diet. I was conditioned to follow strict food rules from the 4th grade when I was exposed to them at an Orthodox Judaism school. And I have even eaten processed foods like chocolate vegan milk recently, which I would not have touched when I started this diet. The reason I almost immediately went vegan and maintained a diet unflinchingly after reviewing my lab results is because of my terror of needles, knowing that I would have to give myself regular shots if I developed diabetes. I fainted when I had those lab-tests done, and have not repeated any full set of tests since. Thus, if that stomach-doctor had told me in 2016 that the solution was to give myself Ozempic shots it would have been as strong or stronger of a “no”, as his ideas about a colonoscopy etc. being relevant. That stomach-doctor declared bankruptcy shortly after my visit, so this financial pressure must have been the reason for his strange refusal to see a patient to help with solving problems cheaply. Given these facts regarding my own experience, the weight-loss-shot trend is horrifying. If the drug is maintaining the weight loss, then going off this drug is equivalent to me reversing all my pre-weight-loss practices, including not drinking water, not exercising, and eating twice more calories of non-vegan fatty food. Staying on any drug for a lifetime is obviously as damaging to health as being an alcoholic or a tobacco smoker, especially if the drug is designed to fool the body, altering its chemistry, etc. Weight-loss surgeries work because they make people vomit if they attempt to over-eat, forcing adherence to a diet, until the stomach or the like re-expands and can again take in over-sized bunches of food. Because veganism works by over-filling the stomach with food that convinces the brain it is full earlier than compressed processed food would with equivalent calories, somebody who has had weight-loss surgery cannot also go vegan and take advantage of such fruit/vegetable-bulking. Eating half-a-watermelon for lunch would be far safer to make somebody feel full than getting a shot that makes them feel so noxious they do not want to it. I just wanted to insert this public-service-announcement before looking inside this book to warn readers away from this idea: giving this warning was my motive for requesting this book.

The subtitle of this book is at least not a pure puffery as it refers to the extremes of “Extraordinary Benefits and Disturbing Risks”. But then the “Contents” page of Hari’s book includes a typo in the subtitle of “Chapter 1… How he Drugs Work”. The first chapter that caught my attention is the one that seems to argue against my previous paragraph: “Chapter 6: Why Don’t You Diet and Exercise Instead?” Hari begins by describing a dinner out he had with a friend when “he shoveled some breaded chicken schnitzel”. I have not dined out (except for during conference trips when all rules are out) since I moved to my tiny house in Quanah in 2017. There are no fancy or semi-fancy restaurants in my region, so dining out means cheap fast-food, which is not appealing, even if I was not vegan. As soon as I realized I was morbidly obese, I decided to avoid such fast-food or minimize it. So I do not understand how Hari is actively eating this stuff, and is contemplating diabetes shots instead of just putting the “schnitzel” down. His friend asks him this same standard question. He answers that since his “late teens” he had “diligently tried” this “usually around once a year.” Why would not eating out, or eating a vegetable once a year be a serious attempt at weight loss? Obviously, whatever anybody does for 1/365 days is not going to have any meaningful impact on our weight. The obstacle that stopped him after this vigorous day was “hunger”. What? Not eating out for a day makes him hungry? Is he going from eating a wagon-of-fat to nothing, maintaining the near-zero calories until he is starving and then returning to the wagon? Why isn’t he snacking on fruits, or nuts or anything reasonably low-calorie throughout his diet days to make sure to avoid feelings of hunger preventing slide-backs? Then, he goes to a clinic for an “intestinal cleansing therapy”. The colon etc. is self-cleaning: everything in it comes out eventually somehow. If special cleaning is necessary due to constipation, eating half-a-watermelon is more likely to “clean” it thoroughly than over-the-counter drugs, or the invasive stuff that can happen at an over-priced clinic. The more fiber we eat, the faster the “intestinal” stuff is going to exit. Just a basic tip in case Hari is going to ponder the options in the future. Hari then describes that he was served “stale” bread deliberately at this clinic to teach him “to chew”. Amazingly, Hari remained in this facility, and listens with amazement to an absurd lecture on chewing technique and silent eating. At this point I realize that this chapter is supposed to be about simply exercising and eating less, and instead of just trying this, Hari has taken on a money-wasting exercise that has him having “tea” for all his meals, without meeting the caloric minimum necessary to avoid the extreme-hunger he was afraid of at the onset. When he is refused food days in, he stages an “uprising” by eating “pizza”, and leaving without his deposit. Those who run that facility know that everybody will fail and either will have paid in advance, or will return again after hunger forces them to binge after a stay. The scientists at these facilities spend their time investigating how to make people pay as much as possible, while having to provide as little food as possible, and maximizing recidivism. They win if their diet-plan fails. The simple advice is, eat less and exercise, not starve and meditate in silence. The reason 95% of dieters fail is because the diet-industry makes billions if most diets fail, whereas it would make no money if they gave advice that led to success. For example, telling a patient to go vegan and to eat as much as they want has been proven by studies to lead to significant weight-loss, which continues if veganism is maintained. It would take a few seconds for a doctor to tell a patient to go vegan and to thus increase fruit-vegetable-bean-bread-oats-etc. fiber consumption. Since this can happen during an unrelated appointment with a non-specialist, this doctor would make $0 extra for this medical prescription of good food. The patient can then lower their grocery bill by maintaining this diet. In contrast, any wellness guru who can give nonsensical advice that does not work can pocket hundreds or thousands for continuous streams of nonsensical lectures, and then this patient is forced to seek out another nonsense-lecturer or servicer who makes even more to make sure than 95% of clients fail and keep paying into this system. Weight-loss-shots that cost thousands are an example of extreme profit-margins, as the production of this drug costs pennies, and if 25% of a population were on these drugs this would equal the cost of 25% of the population having entirely unnecessary surgeries annually.

In “Chapter 7: The Brain Breakthrough”, Hari begins by reporting that he has started taking Ozempic, but while he believed (without reporting the numbers) that he was losing weight, he started feeling that his “mood was strangely muted. I didn’t feel as excited for the day ahead… I felt a little listless…” Only when he was facing clinical depression did he then begin researching “the brain effects”. He writes that the drug is supposed to work because “They are an artificial copy of a guy hormone—GLP-1—that tells you when you’re full. The real hormone lasts for a few minutes and then vanishes; the replica lingers for a whole week.” It is “boosting fullness and slowing digestion.” One of the most-frequent pieces of advice for weight-loss is increasing metabolism, which means speeding up digestion, and yet this drug performs the opposite function. Additionally, Hari realized that GLP-1 is produced in the brain, so the reduction in appetite really happens by manipulating the normal chemistry in the brain. He then cites a study that claimed that GLP-1 injected into the brain causes a “cut back on” specifically “junk food”, and the consumption of the same amount of “normal” food. This is absurd because there is no rat “junk-food”, as rats are fed rat-food… He goes on to speculate that this drug can dampen addiction, but this is entirely a false argument because he started this digression by explaining that GLP-1 is a hormone that the body releases specifically when somebody has eaten too much to signal fullness, and to slow digestion because there is too much food to process. The Mayo Clinic explains it thus: “When blood sugar levels start to rise after someone eats, these drugs stimulate the body to produce more insulin. The extra insulin helps lower blood sugar levels.” They are used by diabetics in combination with insulin because they have a parallel effect on blood sugar levels. This process can only be making somebody noxious instead of full because a drop in blood sugar level should stimulate new natural hunger to bring the blood sugar level to a stable level. If there is an artificial chemical constantly lowering the sugar level, this must be an enormous risk towards developing diabetes, just as giving somebody who is non-diabetic insulin can trigger the start of diabetes. This is all extremely disturbing. Every time I hear somebody talking about a trend towards widespread usage of these drugs, I am horrified, and reading this conversational account explains how people who fail to look up definitions on Mayo Clinic (at least) are fooled by such personal-narratives.

I hope nobody reading this review will try these drugs, nor read this book. Just listen to my free advice: exercise and eat more fiber in real food.

Puffery for Increasing Police Budgets, Despite Unsolved Crimes Credited to a Lump of Multi-Ethnic-and-Multi-Ideological “Anarchists”

Steven Johnson, The Infernal Machine: A True Story of Dynamite, Terror, and the Rise of the Modern Detective (New York: Crown Publishing, May 14, 2024).

***

“Account of the… struggle between the anarchist movement and the emerging surveillance state stretches around the world and between two centuries—from Alfred Nobel’s invention of dynamite and the assassination of Czar Alexander II to New York City in the shadow of World War I. April 1914. The NYPD is still largely the corrupt, low-tech organization of the Tammany Hall era. To the extent the police are stopping crime—as opposed to committing it—their role has been almost entirely defined by physical force: the brawn of the cop on the beat keeping criminals at bay with nightsticks and fists. The solving of crimes is largely outside their purview. The new commissioner, Arthur Woods, is determined to change that, but he cannot anticipate the maelstrom of violence that will soon test his science-based approach to policing. Within weeks of his tenure, New York City is engulfed in the most concentrated terrorism campaign in the nation’s history: a five-year period of relentless bombings, many of them perpetrated by the anarchist movement led by legendary radicals Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman. Coming to Woods’s aide are Inspector Joseph Faurot, a science-first detective who works closely with him in reforming the police force, and Amadeo Polignani, the young Italian undercover detective who infiltrates the notorious Bresci Circle.”

The “Preface” begins dramatically with the details of the types of bombs that caused the disturbances in Manhattan: “more inventive ones utilized a kind of hourglass device releasing sulfuric acid into a piece of cork, the timing determined by chemistry, not mechanics: how long the acid took to eat its way through the cork, until it began dripping onto the blasting cap below.” Such researched details are unusual in combination with dramatic action in mainstream non-fiction, so this is a good start. Then, Johnson defines the term “anarchist” and the movement that used this term, using uniquely insightful political theory.

However, then the narrative turns to a puffery of investigative procedures, concluding that before the CIA and FBI, the NYPD created a method that stopped this “anarchist” movement by solving whodunnit regarding the bombings. There are enormous numbers of bombs that are annually exploded across the US today, and the only difference is that all those who operate such attacks are no longer joined together under the umbrella of “anarchist”, as they were at this period, since Johnson explains that this term covered Russians, Italians, communists, far-righters etc., or pretty much all outsiders. It is also a puffery to suggest the NYPD was corrupt in or before 1914, and is no longer so, as this institution has remained equally corrupt across its history, and rather if it is described as corrupt or not in the press that has changed across this past century. The ridicule of police in the press has been censored, so that when cases of police corruption surface these are now presented as outliers. The US is not less corrupt than countries that are described as extremely corrupt in the media, the media in those other countries are simply freer to describe corruption when they see it. Most of the remainder of this “Preface” is thus a puffery, which celebrates the “Identification Bureau”, which merely contained “file cabinets containing tens of thousands of photographs and fingerprints”, or the bare minimum necessary to attempt a criminal investigation in an enormous city such as New York.

Then, “Chapter 1: The Controlled Exposition” takes the narrative back to 1866 in Germany, which oddly begins with a detailed description of the “living organisms” that died millions of years earlier to create a dune’s sand, just to situate this period as being about the time of “Darwin’s” evolutionary theories; as I explain in my new series, and other scholars have recently noticed, “Darwin” plagiarized an earlier French scientist’s evolution research from a hundred years before that time, so using Darwin as a time-setter is simplistic and irrelevant. Then, the more relevant science of “nitroglycerine detonations” by “Nobel” is described. But this is a complete digression from the subject puffed in the “Preface” or the promise that this book would show evidence of genius detective-work at the NYPD. There are 3 parts in this book, and only the third part is about the investigation itself.

“Part Three: Detonation: 1914-1919” would in theory begin with evidence of what the police did successfully, but it instead begins with the allocation of funds to start a new police wing, which happened because operators in the department were able to cluster unrelated incidents as the work of “anarchists”, thus convincing city-leaders that this was a coherent threat that required money. When there are details, they report various “radical” incidents and publications, such as Howard Zinn’s “master’s thesis” about the Ludlow massacred, followed by Woody Guthrie’s ballad, “Ludlow massacre.” The next chapter describes protests. There are many digressions with descriptions of irrelevant items such as clothing: “Alexander Berkman strode confidently out of the Tarrytown train station, a cane in one hand, dressed in a crisp dark suit, with a white tie and pocket square.” Without citations, these clothing details can be entirely fictitious, as, for example, there is no way of looking into Berkman’s mind to check if he indeed felt “confident”. Then “Chapter 20: The Blast” begins again irrelevantly with a sunrise in the “summer heat”, before an explosion at 9:06am. Then, finally, there is a relevant description of the damage from this bomb. Then, there is another interesting narrative that explains that back in May through June “someone had begun quietly but persistently removing sticks of dynamite from the construction site.” This is the first sign of investigative research into the central promised subject of this book, but there is no explanation regarding which detective learned of this detail. The next paragraph clarifies: “Much mystery remains about the exact manner of the theft. Was there an inside man on the IRT payroll who was fencing the dynamite on the side?…” In other words, somebody at this construction site reported these thefts to the police and that’s how this case was solved. But the police failed to ask basic whodunnit questions like the one mentioned that could have in fact detected what led to this bombing. This proves that despite added funds to the police department, no improvement in actual detection was generated, or that the puffery of the NYPD in the preface is undeserved.

If somebody is searching for a mystery semi-fiction to read under the hot summer sun, this might be an enjoyable read, but for those who want to understand how budgets of police departments have grown without any progress in policing… you have to read between the lines of this propagandistic support of incorruptible policing.

An Incompetent Forgery Builds America’s Economy: Described in Digressive Imaginings

William Hogeland, The Hamilton Scheme: An Epic Tale of Money and Power in the American Founding (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, May 28 2024).

**

“How Alexander Hamilton embraced American oligarchy to jumpstart American prosperity. ‘Forgotten founder’ no more, Alexander Hamilton has become a global celebrity…. What did he really want for the country? What risks did he run in pursuing those vaulting ambitions? Who tried to stop him? How did they fight? It’s ironic that the Hamilton revival has obscured the man’s most dramatic battles and hardest-won achievements—as well as downplaying unsettling aspects of his legacy. Thrilling to the romance of becoming the one-man inventor of a modern nation, our first Treasury secretary fostered growth by engineering an ingenious dynamo—banking, public debt, manufacturing—for concentrating national wealth in the hands of a government-connected elite. Seeking American prosperity, he built American oligarchy. Hence his animus and mutual sense of betrayal with Jefferson and Madison—and his career-long fight to suppress a rowdy egalitarian movement little remembered today: the eighteenth-century white working class.”

The above blurb promises a less propagandistic American history than most. The introductory chapter does not continue this intense truth-telling, as it is mostly digressive, discussing all periods of American history, and even barely explaining what Hamilton actual policies were as it attempts to summarize the contents of the chapters. Then, “Chapter 1” is again very digressive as it describes some sort of an effort “to get rich quick” in 1741 by Hamilton, referring generally to some “British colonials in the Caribbean… making more and more money exporting more and more sugar…” One of the rare interesting specific details is the mention that as part of his success in New York came his “changing his birthdate to 1757” to appear to be a “wunderkind” as he began studying at Kings College in 1773. In other words, he started his studies with fraud, and so much have basically purchased a paper-degree, without doing real intellectual work, or such a forgery would have been noticed by administrators. Then, there are general references to some kind of business speculation, most of which tend to claim Hamilton succeeded by fooling socialites to give him money and power, as his “father-in-law” curated “friendly connections with the right people.” With barely a degree, and with wealthy corrupt connections or nepotism, Hamilton ended up in charge of directing American financial policy by 1781. Most of this book is hot air, where the writer appears to be imagining what people felt or believed, instead of researching the “history” of what happened. The next chapter includes a few rare specifics such as that Morris, Hamilton’s affiliate, “sorted out empires’ and companies’ various exchange rates for paper currencies and notes against real money… gold and silver coins”. The author digresses into the definition of “real” and “silver”, without quoting any source or simply explaining just what Morris’ job was, why it was significant, and why the narrative has digressed into such abstractions instead of attempting to support the ambitious promised thesis of being an anti-propaganda about just what Hamilton’s economic plan for America was.

This is a horrid book. It might eventually get to a point, and it might include scandalous details, instead of standard puffing propaganda, but these details are enclosed in pages and pages of unresearched nonsense. Nobody should read this book unless they want to be frustrated and confused.

Confessions of a Drug-Addicted Black-Hat-Hacker

Barrett Brown, My Glorious Defeats: Hacktivist, Narcissist, Anonymous: A Memoir (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, July 9, 2024).

***

“Barrett Brown went to prison for four years for leaking intelligence documents. He was released to Trump’s America. After a series of escapades both online and off that brought him in and out of 4chan forums, the halls of power, heroin addiction, and federal prison, Barrett Brown is a free man. He was arrested for his part in an attempt to catalog, interpret, and disseminate top-secret documents exposed in a security lapse by the intelligence contractor Stratfor in 2011. An influential journalist who is also active in the hacktivist collective Anonymous… He exposes the incompetence and injustices that plague media and politics, reflects on the successes and failures of the transparency movement, and shows the way forward in harnessing digital communication tools for collective action.”

The first chapter begins with a description of a prison. He has threatening interactions with guards and inmates and reports “the loss of my books”, which he had access to together with a radio at a different prison. Then, some “Hispanic fellow” down the hall yells that he will “send you some coffee tonight! You’re awesome, Brown!” This makes him think of himself as one of the “saints”, who has been shamed. While it is important to describe poor conditions in prisons: what does this have to do with the subject advertised in the blurb? The section ends with concerns that the FBI and “Themis” have an “ability and willingness to dig up dirt on activists’ children using social networks”, and other general theories of conspiracy that are detached from the actual actions that led this guy to be imprisoned. Specifically, Themis was planning cyber attacks on WikiLeaks’ anonymous submitters, or to submit “fake documents”, to call WikiLeaks out on fabrication. At this point, I just looked up Barrett Brown’s Wikipedia page, as it seems he might never get to what he was accused of in this book. Brown is a journalist who confessed his association with Anonymous, but had disassociated from it by 2011. Apparently, he previously contracted for $100,000 with Amazon to write a book specifically on Anonymous, but spent the money and never wrote this book. Brown notes in the book that there was an attempt for “hackers… to bring down the Amazon site” with around 1,500 participants; this suggests that Amazon might have paid Brown $100,000 as a ransom to stop leading Anonymous missions that attacked their website. So instead, this book is apparently an avoidance project that does not confess his actual hacking activities. And apparently Brown staged a kidnapping attempt and an outing of 75 Zetas gang members to promote an earlier book in 2011. And several other similar incidents followed in 2011 before the FBI began prosecuting him in 2012. “In 2010, he founded Project PM, a group that used a wiki to analyze leaks concerning the military-industrial complex.” So he is complaining generally about potential government spying… because he had designed a program that aggravated espionage sources on the military-profiteers? Specifically, he mined through hacked-by-others emails for information on “Romas/COIN” that was designed to spy on Arab countries. He was sentenced to “63 months in federal prison” for nebulous claims of “obstruction of justice” and had to pay “$900,000” in damages to Stratfor, the military-contractor he had outed as being a corrupt war-profiteer. The reason this book is disjointed is apparently because Brown has confessed heavy drug usage of meth, as well as paranoia and other mental illnesses.

I am now going to search this book for the key terms in this bio instead of attempting to find some lineal meaning. When discussing “Anonymous”, Brown writes its techniques included “drawing upon obscure network protocols to allow internet users to temporarily knock out websites via sheer blunt force”. Or “outright hacking… a raid of Turner’s email account yielded proof that he’d served as an FBI informant, confirmation of which cut him off from his white nationalist allies—as well as from the FBI itself”. That’s something American propaganda films don’t show. Hackers are outing informants to prevent the FBI from gathering data on white-nationalist groups? Why would such activities be useful for anybody other than the white-nationalist groups? Brown claims that it is nonsensical to believe that Anonymous could “be capable of taking control of the nation’s power plants.” He explains that the name “Anonymous” came from 4chan using the “default… username ‘Anonymous’” for anybody who did not want to enter “a screen name”. In another section, he comments on Anonymous’ use of “lulz” to refer to their “pursuit” of malicious pranks, such as “messing with online children’s games like Habbo Hotel”, or a “‘nationwide campaign to spoil the new Harry Potter book ending.’” He quotes an anonymous Anonymous member for the last quote, as opposed to his own activities.

Regarding Zetas, Brown writes that a “dealer” who was “connected to the Mexican contingent of Anonymous” was indeed kidnapped. He confesses that he assisted this operation of freeing the kidnapped affiliate by threatening with outing gang-member names. But the press “promptly decided that I myself was in charge”. He then faced threats of retaliatory assassination by the gang, and then the narrative gets confused because of Brown’s consumption of large quantities of drugs while on this job. He leaps to a discussion of receiving requests from one conservative blogger to hack another conservative blogger to prove the assertion that one of them was an “antisemite” to win a “dispute” between them. He includes a discussion where he points out this would be illegal, but which seems to end with him neither agreeing nor disagreeing to go ahead with it. By not explaining what he decided to do, he seems to be advertising his malicious hacking services of this type to future potential clients.

In summary, this book confesses with light details the types of hacking services Brown has been selling to clients on all sides to attack anybody for money. However, the lack of technical details about just what the hacking process involves indicates that it is likely that Brown only connects clients with hackers, instead of having the knowledge to fabricate such attacks himself. The re-branding of Anonymous as a white-hat organization is certainly countered by books such as this one that explains its purely nefarious intentions to gain profit, and various other benefits (girls, drugs), without caring if either the hackers or those attacked are hurt (though attempting to protect themselves through anonymity, unless revealing their identity can be used to sell a book, merchandize or the like). If anybody out there is curious about Anonymous and does not mind sifting through a lot of nonsense to mine out bits of sense, they can benefit from this book. But they really have to purchase an ebook and search for terms that interest them, as reading the starts and ends of chapters or other standard strategies are not going to be helpful in decoding this project.

Biography of an Impressionist’s Struggle for Fame

Jackie Wullschläger, Monet: The Restless Vision (New York: Knopf, Pantheon, Vintage, and Anchor: Knopf, September 24, 2024).

****

“Drawing on thousands of never-before-translated letters and unpublished sources, this biography reveals dramatic new information about the life and work of” Monet. “Despite being mocked at the beginning of his career, and living hand to mouth, Monet risked all to pursue his vision, and his early work along the banks of the Seine in the 1860s and ‘70s would come to be revered as Impressionism. In the following decades, he emerged as its celebrated leader in one of the most exciting cultural moments in Paris, before withdrawing to his house and garden to paint the late Water Lilies, which were ignored during his lifetime and would later have a major influence on all twentieth-century painters both figurative and abstract. This is the first time we see the turbulent life of this volatile and voracious man, who was as obsessed by his love affairs as he was by nature. He changed his art decisively three times when the woman at the center of his life changed; Wullschläger brings these unknown, passionate, and passionately committed women to the foreground. Monet’s closest friend was Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau; strong intellectual currents connected him to writers from Zola to Proust, as well as to his friends Manet, Renoir, and Pissarro.”

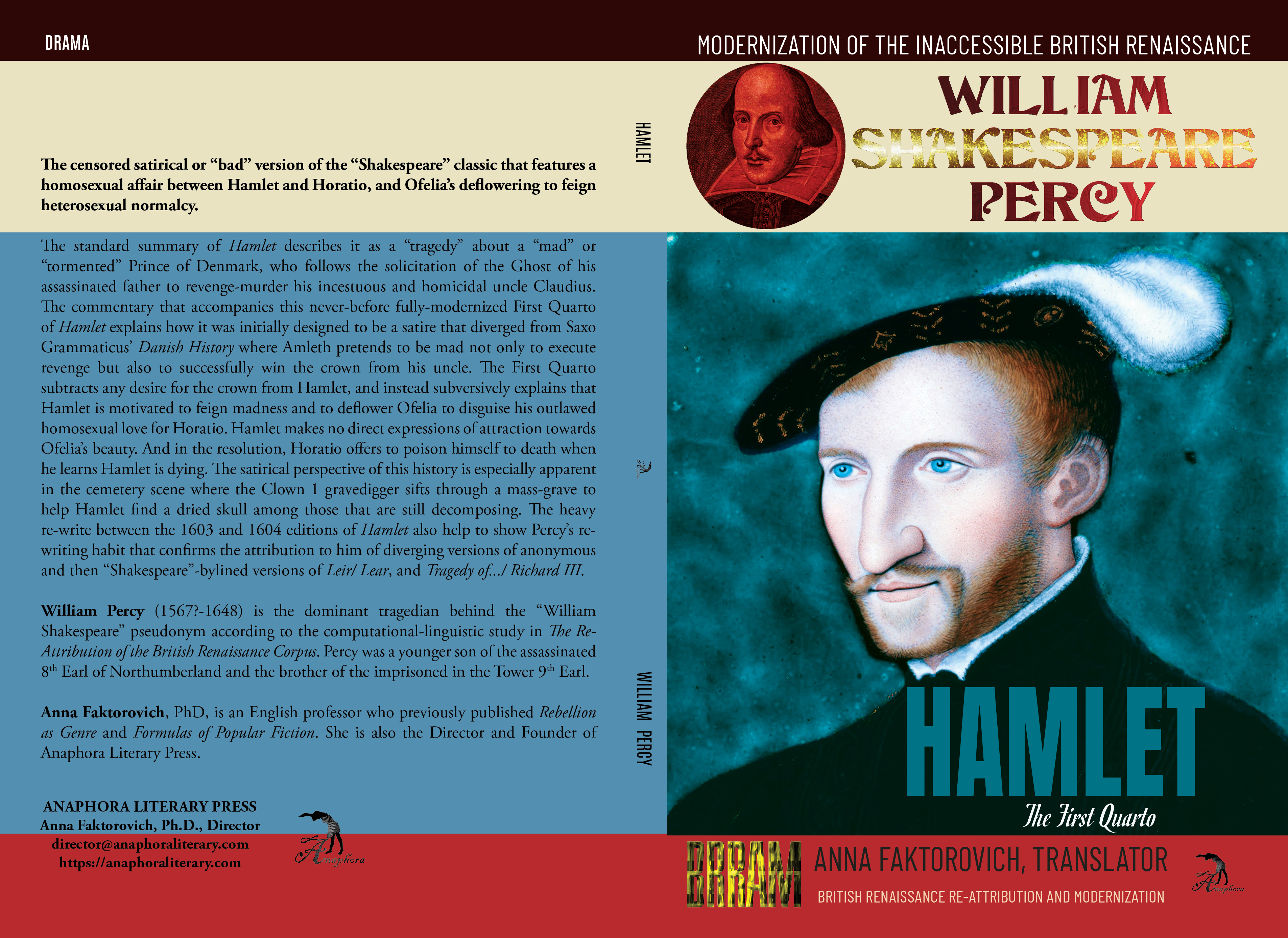

This book is organized chronologically. The “Introduction” explains that the author began this research project because she realized Monet’s private life had been un-researched, and had found a catalogue of Monet’s 3,000 letters that had mostly not been translated before. Then, the “Prologue” describes Monet’s dramatic sketching of his newly dead girlfriend in 1879. A curious explanation follows that Monet had drawn around “fifty pictures” of Camille during her lifetime… But after her death, he hardly depicted a figure again.” The changes in Monet’s art with the three leading women in his life, Camille Doncieux, Alice Raingo and Blanche Hoschede, suggest to me that these women were the artists, who drew in different styles under “Monet’s” byline. But the author seems to interpret these changes as emotional impacts that were sufficient to alter artistic choices of the single male artist. Most of the description is about the emotion evoked by these Impressionist paintings, as they are described as being the “opposite of restrained”. Analysis of the letters focuses on Monet feeling “always hungry, always greedy”, and otherwise emotional. None of this is practically useful to modern artists who want to read about the lives of artists to learn the tactics that create superior art. Monet is also presented as somebody who in his “youth” “built Impressionism on his confidence”, ignoring that this was a movement that is credited to numerous different artists, some of whom preceded Monet. If Monet was its sole inventor, was he ghost-painting under others’ bylines? Otherwise how can he be singled out for his exceptionalism without acknowledging that he used a style that was communally shared by many others?

The first chapter of the first part begins with just how little is known about Monet’s childhood, as, for example, he described himself merely as “a Parisian from Paris”. This refusal to share details suggests to me that there was a ghost-artist behind the Monet byline who did not care to learn who Monet was, and could only write letters etc. from “Monet’s” perspective after Monet had joined an artist Workshop and made his activities known. Most of the following biography of his childhood is imagined based on the history of the region where he lived, and sparse records. Then, finally, there is a description of Monet’s first “pair of sketchbooks from summer 1856” when he was 15. “Monet gives a glimpse of Ingouville’s bourgeois houses, set in parks with paths framed by yuccas and umbrella pines, suggesting already an appeal of gardens, of nature tamed, enclosed and decorative, as a counterpart to the attraction of the open sea”. What is missing here is just how Monet learned to draw, what his techniques were and how they changed. Instead, the interest is Monet’s interest in the sea, water, and other irrelevant abstractions (1-18).

A few pages later there is a note that Monet launched his artistic career as a “caricaturist”, by “circling the rue de Paris” and selling “caricatures of the town’s notables” in window displays. A few pages, there is a report that Monet was making “commissions” on portraits”, the number of patrons doubling in a month, together with his charge stabilizing at “20 francs”. From this childhood enterprise, the narrative leaps to when Monet was 30 in 1854, when he had grown tired of the repetition of caricature painting, and wanted to be famous. To solve this problem, Monet befriended Boudin, who was poor but connected to famous artists (19-30). Earlier, “he lived in Paris for four years, from the ages of sixteen to twenty, funded by an unlikely 2,000 franks earned from his caricatures”. Though the author reports that Monet claimed to have gone to Paris much earlier than when he actually went two years later (35). Immediately upon his arrival, Monet was greeted with help, as “Charles Monginot… offered Monet the use of his studio”. There is a report that Boudin was painting “for a free… Troyon’s skies for him”, or ghost-painting. Then, there are digressive comments about Monet’s friends, hints that he obtained some tutoring from artists, and his associations with folks like a “radical journalist” for whom Monet “copied Nadar’s caricature” (45). Monet’s strategy to be noticed was to chat in cafes to make connections and to draw paintings to be hung in the Salon, hoping they would be noticed, puffed, and purchased (47).

I found myself drawn into this narrative. Many paragraphs contain irrelevant information, but it is all well-researched as opposed to airy. An artist who is interested in how somebody practically becomes famous in art will find many useful lessons here. Thus, I recommend this book for aspiring and mature artists, and for libraries of all types where artists might seek inspiration and information.

A Bunch of Random Stories About NFT-Related Stuff

Zachary Small, Token Supremacy: The Art of Finance, the Finance of Art, and the Great Crypto Crash of 2022 (New York: Knopf, Pantheon, Vintage, and Anchor: Knopf, May 21, 2024).

**

“In 2021, when the gavel fell at Christie’s on the sale of Mike Winkelmann’s Everydays series—a compilation of five thousand digital artworks—it made a thunderous announcement: Non-fungible tokens had arrived. The ludicrous world of CryptoKitties and Bored Apes had just produced a piece of art worth $69.3 million (at least according to the highest bidder). On that day, the traditional art market—the largest unregulated market in the world—put its stamp of approval on a very new and carnivalesque digital reality… Was it all just a money laundering scheme? And come on, what was that piece of digital flotsam really worth anyway?… Tracing the crypto economy back to its origins in the 2008 financial crisis and the lineage of NFTs back to the first photographic negatives. Small describes jaw-dropping tales of heists, publicity stunts, and rug pulls, before zeroing in on the role of ‘security tokens’ in the FTX scandal. Detours through art history provide insight into the mythmaking tactics that drive stratospheric auction sales and help the wealthy launder their finances (and reputations) through art. And we cast an eye toward a future where NFTs have paved the way for a dangerous, new shadow banking system.”

The introduction opens with a digressive pondering about Renaissance art and tulip mania. Then, there is a definition of the central promised subject of this book: “NFTs” are “recording transactions for digital goods and providing creators with access to resale royalties.” This is followed by a realistic note that this simple goal was side-tracked into ideology, as users began describing themselves as “human gods” to drive speculation or a steep irrational increase in NFT prices. Then, the tulip bubble is compared to this new mania. Then, finally a revelation: Rembrandt was “bidding on his own paintings” to solve his “money problem” that escalated into bankruptcy. This led Amsterdam’s painters’ guild to institute “a new rule: nobody in Rembrandt’s financial circumstances could trade as a painter.” But the starving-artist trope is pretty much why any artist has achieved fame in the past? Histories tend to report that some kind of publicity stunts, or manipulations of markets were involved in making any artist famous above billions of others. An example is the art thefts in Picasso’s circle, which indirectly spiked the value of Picasso’s art through the publicity associated with imprisonment of his affiliates. A description follows of a gallery showing without any art on blank walls, when $7 million in sales happened at a single event, orchestrated by Hobbs, who was a specialist in “code” in “cryptomania”. NFT’s can theoretically prevent forgeries, but when the “code” sells without any serious art behind it, then it is not protecting art from being duplicated, but is rather selling nothing for enormous sums by merely marketing it or puffing its cultural value. They were taking advantage of a pandemic that was keeping people away from physical art-shows to sell empty digital space. While there are some interesting ideas here and there, this book lacks coherent structure to systematically research this complex subject to arrive at concrete useful answers. The author reports that this began his research by spiking his curiosity.

Then, chapter “1: The New King of Crypto” begins with an attempt to put readers to sleep by describing a guy sitting on a sofa. Then, finally there is a description of Beeple as a series that began by doodling on “internet bile (racist caricatures, nude women… political satire)” before using animation software in 3D. It just gets more unreadable after this point, as the author digresses into random characters in this world without explaining where these stories are going, without citing sources, and just generally altering from puffing specific NFT providers, to ridiculing them as being absurdly counter-artistic.

There is probably some kind of useful information somewhere in this book but it is hidden under piles of digressive meaningless ramblings and ponderings. Why couldn’t this author sketch out an outline for what he was planning to say, create sub-sections in chapters that specify what NFT creators they cover, why each is significant, and then have some chapters that analyze trends? Instead, all chapters have puzzling titles such as “We’re All Gonna Die”. And the narrative just runs wherever Small feels like going, as if he just kind of sets a timer to babble for an hour before bed, when he is too sleepy to do real work, about dudes he met online that day. Unless all this sounds interesting to you, do not attempt to read this book.

Casually-Philosophical Ponderings on Paradoxes

George G. Szpiro, Perplexing Paradoxes: Unraveling Enigmas in the World Around Us (New York: Columbia University Press, March 26, 2024).

***

“Why does it always seem like the elevator is going down when you need to go up? Is it really true that 0.99999… with an infinite number of 9s after the decimal point, is equal to 1? What do tea leaves and river erosion have in common, per Albert Einstein? Does seeing a bed of red flowers help prove that all ravens are black? Can we make sense of a phrase like ‘this statement is unprovable’?” It “guides readers through the puzzling world of paradoxes, from Socratic dialogues to the Monty Hall problem…. Presents sixty counterintuitive conundrums drawn from diverse areas of thought—not only mathematics, statistics, logic, and philosophy but also social science, physics, politics, and religion. Szpiro offers a brisk history of each paradox, unpacks its inner workings, and considers where one might encounter it in daily life. Ultimately, he argues, paradoxes are not simple brain teasers or abstruse word games—they challenge us to hone our reasoning and become more alert to the flaws in received wisdom and common habits of thought.”

The book is organized into sections on the “Silly and Surprising”, “Language” tricks, the “Unbelievable but True”, “Math”, Physics, Statistics, Philosophy, Logic, Faith, Legal Terms, Economics, and Politics. The introduction helps to explain the subject of “paradoxes” by examples such as that Theseus “asked whether a ship whose rotten planks have been replaced one by one over the years is the same ship as the original”. More usefully Quine is quoted: “A veridical paradox packs a surprise, but the surprise quickly dissipates itself as we ponder the proof. A falsidical paradox packs a surprise, but it is seen as a false alarm when we solve the underlying fallacy…”

So, the first part on “Quotidian Riddles” begins with a chapter that explains the statistics of why most people on average have friends with more friends than they do. The explanation is that outliers with too many friends are likely to skew the statistics in their friend-groups. The following explanation includes almost no numbers, and does not really address the falsehood in this assumption, or data-manipulation potential. Chapter “2: Waiting for Godot: The Elevator Paradox” thankfully begins by answering the conundrum logically. It takes longer for people to see an elevator if they live at the top floors. Physicists studying the problem found that “there is one-in-six chance… that the first elevator he encounters will be going up. But there’s a five-in-six chance… that the first elevator will be going down.” What? How can there be such a small chance of either of these seemingly 50/50 choices? No numbers were given previously to explain how these statistics were arrived at. This mathematician is not showing the work, as the author seems to be summarizing conclusions reached by others without attempting to follow the logic, or being seriously interested in presenting the precise reasoning behind a solution. Thus, those who are interested in advanced statistics are going to be deeply frustrated, as they either have to search for each of the mentioned studies to figure out what this guys is talking about, or just leave each section with a deep sense of disbelief and confusion. The next section on “hedonism” is at least more appropriate for general philosophical reflection: “constant pleasure seeking may not yield the most actual pleasure or happiness” because “the constant pursuit of pleasure interferes with the experience of it.” “John Stuart Mill” explained it thus: “Those only are happy… who have their minds fixed on some object other than their own happiness… Ask yourself whether you are happy, and you cease to be so.” This is a deep useful conclusion that should help those suffering with depression by just having them think about others and on achieving some kind of a goal outside of themselves.

This is basically a silly book that attempts rudimentary philosophy. If you are bored and would like to be entertained with curious ponderings on strange puzzles, you might enjoy this book. But anybody who enters this book with a serious interest in being amazed with new discoveries about the world will leave it with a deep sense of unhappiness.

If a Revolution Is a Turn Where You End Up Where You Started: Hallucinogenics

Joanna Kempner, Psychedelic Outlaws: The Movement Revolutionizing Modern Medicine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, June 4, 2024).

***

“How a group of ordinary people debilitated by excruciating pain developed their own medicine from home-grown psilocybin mushrooms—crafting near-clinical grade dosing protocols—and fought for recognition in a broken medical system. Cluster headache, a diagnosis sometimes referred to as a ‘suicide headache,’ is widely considered the most severe pain disorder that humans experience. There is no cure, and little funding available for research into developing treatments. When Joanna Kempner met Bob Wold in 2012, she was introduced to a world beyond most people’s comprehension—a clandestine network determined to find relief using magic mushrooms. These ‘Clusterbusters,’ a group united only by the internet and a desire to survive, decided to do the research that medicine left unfinished. They produced their own psychedelic treatment protocols and managed to get academics at Harvard and Yale to test their results. Along the way, Kempner explores not only the fascinating history and exploding popularity of psychedelic science, but also a regulatory system so repressive that the sick are forced to find their own homegrown remedies, and corporate America and university professors stand to profit from their transgressions. From the windswept shores of the North Sea through the verdant jungle of Peruvian Amazon to a kitschy underground palace built in a missile silo in Kansas…”

The note in this blurb about independent researchers finding that “Harvard and Yale” professors are willing to put their names on research conducted by others confirms my own findings about the prevalence of ghostwriting in academia since the dawn of print in the Renaissance through the present. Pharmacological science was primarily created by a couple of ghostwriters across Britain’s 18th and 19th centuries, as famous bylines such as “Darwin” and “Newton” were one of many bylines that referred to merely 11-12 active ghostwriters across all genres per century. This book opens with the “Psychedelic Timeline” that begins in 8000 BCE when “Psychoactive drug use across globe indicated by archeological evidence.” The next entry is from 1799 when “The London Medical and Physical Journal publishes the first medical description of a psychedelic mushroom experience, which it characterizes as a poisoning.” My current research of handwriting and linguistic evidence from the Royal Society’s archives for the 18th century indicates only around 4 different handwriting styles across their scientific manuscripts, which have been assigned to hundreds of different puffed bylines. And frequently, as in “Darwin’s” case, scientists in other countries solved puzzles such as evolution at least a century earlier, but Britain’s propaganda machine claimed that they were first by forging manuscripts that had earlier dates (“Newton”), or simply ignored earlier foreign claims from the French etc. (“Darwin”). Across the Opium Wars with China, Britain was fighting for opium, while it was China that was attempting to block Britain’s corrupting influence that was poisoning its population. Mushrooms had been used as psychedelics from around the 8000 BCE point just mentioned, and Britain only learned about this use in 1799, and yet its “discovery” is used as this field’s origin-point. Those who are in academia pay for paper-degrees, and for ghostwriters to write their papers, as industry also hires ghostwriters to create papers that help them maximize their profits by keeping humanity maximally sick. While the pharmaceutical invention industry is thus entirely corrupt and has no room for authentic scientists who are purely interested in curing diseases, it is hardly a good solution for the few scientists with access to home-labs to seek escapist drugs that merely help to mute reality, without curing anything. The concluding years in the timeline between 2017-23 are marked by FDA’s approval of MDMA and other psychedelic drugs for medical use, after papers arguing for this from the “Harvard and Yale” scientists that had their papers ghostwritten in previous years. It is safer for society if those who want to use mind-bending drugs to do it legally, as they had done it a century earlier when the first drug-bans were instituted. But this history is a circle that began with profit-driven bans, and has circled back to profit-driven permissions. There isn’t exactly progress that has been made, but rather a nonsensical battle that led the field back to its starting-point.

The “Introduction” opens with a painful description of the debilitating condition of an extreme headache. This possibility of debilitating pain is used as a motive to explain why mind-altering drugs or “magic mushrooms” is the solution. Sympathy for somebody in pain might drive readers to agree with this argument, but upon rational reflection: why would it be a good idea for somebody who is experiencing extreme suicidal pain to also be seeing things that are not there in combination with this pain? Having altered beliefs about reality, or hallucinations would only be added symptoms on top of the headache that would create a still more serious mental handicap. The outcome, upon serious clinical testing, might hypothetically be extreme violence towards others or one’s self? Instead of this anticipated outcome, this patient reported that a “low dose of mushrooms, which felt to him more like a strong cup of coffee, could suppress his attacks for nearly a week”. Why on earth are these citizen-scientists believing this anecdote? Why would hallucinogenic drugs have an impact equivalent to a stimulant such as coffee? And why would any stimulant suppress pain? And why would a low dose be sufficient to suppress pain for an entire week? Instead of asking any such questions, the author takes this as sufficient to prove his desired thesis or that psychedelic drugs should not be “demonized”, but rather “hailed as a new transformative medicine”. Psychedelics, in fact, artificially manufacture the main known psychiatric disorder: schizophrenia with hallucinations and paranoia. Even recent research on pot has found that it can cause hallucinations, paranoia and can lead to psychosis, or other mental disorders. If a majority of people in any country want to use recreational drugs to create these mental abnormalities; they certainly should be allowed to do so. But they must be informed that this is the intended goal of the usage, instead of giving them propaganda that suggests hallucinogenic are pain-killers, or stimulants. Why do all sides repeatedly find that fooling the public is the only way to convince them or the government to act in a desired way? Shouldn’t an educated society be capable of making rational decisions based on truths? Kempner is aware that he is hitting the market with his intro because as he reports “20 percent of American adults live with chronic pain. Within this group, a jarring 7 percent endure what’s known as ‘high-impact chronic pain,’ a condition that substantially limits daily activities.” And the solution is for these people to also be experiencing hallucinations while they are immobile? The pop-media debate is about if patients’ should be believed by doctors that they are truly experiencing “pain”. All people who start using pain-medications begin experiencing pain, even if they were not before, because withdrawal (even slightly daily withdrawal when the drugs wear off) causes pain. Thus, questioning how one can prove is pain is real is nonsensical, as instead we should be asking why somebody who is healthy has been manipulated to want to take something that will cause them pain?

Instead of exploring these obvious problems, “Chapter One: Psychedelic Outlaws” begins by puffing the modest appearance of one of these civilian-scientists. Then, this book introduces the first concept I have not read elsewhere before: this modest dude tells a crowd that for $100 and in “forty-five days”, they can “produce all the medicine you need to treat yourself for a year”. He then takes a “canning jar” and a “bag of vermiculite”, and gives a lecture on how they can grow magic mushrooms at home. When I was a kid, I picked mushrooms in Russian forests. On an average trip, half of the mushrooms observed were the brightly-colored hallucinogenic or poisonous mushrooms, while the other half was eatable. You don’t need to grow poison at home, you can just go outside, and you’ll probably find something that can make you vomit that’s a fungus. “Drugs” that are given medicinal use really can only be qualified as such if some kind of scientific manipulation or research is involved. After this shocking explanation, the narrative returns to philosophy that puffs hallucinogenic, seemingly under the assumption that nobody will seriously manage to secure the seeds or the like necessary for home-cultivation. The story digresses into racism, how popular drugs are despite their illegality, before reaching this note: “a CIA-funded brothel in San Francisco served as a setting where CIA agents secretly observed as sex workers gave their clients LSD without consent, then attempted to extract information from them after sex.” Can you imagine applying for a job at CIA and then being required to work as a prostitute to poison “clients” to force false-confessions under mind-altering drugs? Why is this useful in supporting the legalization of these poisons?

I am very tired of reading this book at this point. I almost never drink alcohol, never smoked tobacco, and the last time I was forced to use pot by peer-pressure was 20 years ago. I just do not care about this struggle to escape reality, when there is plenty of falsehoods about what is advertised to be reality to need far more presence in actual reality. Anybody who has been reading this and finds that they want to go into this rabbit-hole, is welcome to carry on without me.

Illustrated History of the Bureaucracy in the Path of Original Theatrical Architecture

Richard Pilbrow, and Sir Richard Eyre, A Sense of Theatre: The Untold Story of Britain’s National Theatre (Lewes: Unicorn, 2024). Hardcover: $67.50. 532pp. Index, color photographs on thick paper. ISBN: 978-1-916846-03-6.

****

“The story of the creation of the National Theatre, told by someone who, uniquely, was there from the start, participated in its realisation and has been creatively engaged in the Theatre over the subsequent five decades…. Bridges an… account of the evolution of an architectural masterpiece with a deep exploration of how the building has shaped later theatre making.”

I requested this book under the mistaken belief that it was about 18-19th century theaters in Britain, which I am currently researching for the re-attribution of these centuries. Instead, this book is about a recent theater that was built within the lifespan of its author, as this blurb states. The “Foreword” explains that this National Theatre was uniquely designed to house three theaters in one to allow for a continuous circulation of new plays. Most of this book is a puffery of its “building” as an “ascetic” success. Even notes about earlier criticism are disguised pufferies: “inflated, grandiose, hubristic”. As Eyre notes, theaters have not seen much innovation in their design since Epidaurus or the colosseum structure. There was a slight adjustment in the Renaissance when Roman architectural structures were created in the interior to create a standardized architectural theatrical style that is still reproduced in theaters built up through recent years. Eyre imagines that Frank Matcham’s “horseshoe-shaped auditoriums” were original, but they just move the stage slightly forward into the audience. Instead of describing “modernist” designs of theaters that might have theoretically introduced new concepts, the new aspect in this period is that theaters were apparently judged to be “old-fashioned” and thus not necessary. The obvious problem is that the initial Renaissance theater design was for around 1000-1500 people, where people could see and hear clearly what was going on on-stage (unless their neighboring theater-goers were rioting, or chatting, which was common). In contrast, giant modern theaters place most attendees so far from the stage that they see the actors in tinier forms than if they were watching this show on a home laptop. Leaving theaters small might invite more people to attend the theater, but Renaissance theaters were not profitable (as I explain in BRRAM), and the costs of modern theaters would multiply this unprofitability. Eyre adds that concrete does not help acoustics, and the various other problems with poor design that fails to account for problems most theater-goers are cognizant of. For example, he notes he failed to ask why the building was positioned in the wrong direction, or without facing “St. Paul’s as well as Somerset House”, which would have rationally been the point of placing that theater in that expensive central location (xi). Despite problems, at least this theater “works”, or has been the place where Eyre has been working across his career (xii). Well… that’s not inspiring, but onwards.

Eyre’s relief with the theater’s mere existence is explained in Richard Pilbrow’s “Introduction”, which explains that the idea began in 1848, but the “British establishment took 101 years to come to its support with the passing of the National Theatre Act in 1949.” 13 years after that Sir Laurence Olivier “was appointed” to create it. His first act was to cross out all of the designs that had been suggested for this structure by past architects. And Olivier was not the architect, but rather the manager, whose sole job seems to have been to hire the architect: Denys Lasdun. While this process had taken 150 years, Lasdun self-reported he knew “nothing” about building theaters. And so committees had done absolutely nothing for 150 years while being paid for appearing to commit or to ponder the matter and eventually made the worst possible decisions. For Lasdun, the “spiritual” aspect was of top-importance. The “Author” appears in this narrative after Lasdun’s “labor” has been completed and nothing can be done about the errors in its architecture, and now the business of managing performances began. More committees met with the “Author”. Finally, after this intro, the first photo of the concrete behemoth of stairs-overload is depicted.